The NGT’s action on illegal sand mining in Assam’s Kaldiya river exposes a wider national crisis. Unscientific extraction harms river ecology, groundwater and biodiversity, while sand mafias fuel revenue loss and conflict. Despite strong laws, weak enforcement persists. Technology-based monitoring, alternatives like M-Sand and stronger accountability are essential.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: DOWNTOEARTH

The National Green Tribunal (NGT) expressed strong dissatisfaction with administrative lapses concerning illegal sand mining in the Kaldiya River, Bajali district, Assam.

|

Read all about: RIVER SAND MINING: MEANING, CONSEQUENCES AND WAY FORWARD |

Sand mining is the extraction of sand and gravel from natural environments such as riverbeds, beaches, ocean floors, and inland dunes.

Approximately 50 billion tonnes of sand and gravel are used globally each year, an amount that has tripled over the last two decades. (Source: UNEP).

India's expanding infrastructure and construction sector is projected to contribute about 9% to the GDP in 2025. Annual demand for sand exceeds 1,000 million tonnes, but regulated supply lags, resulting in a large deficit met by illegal extraction.

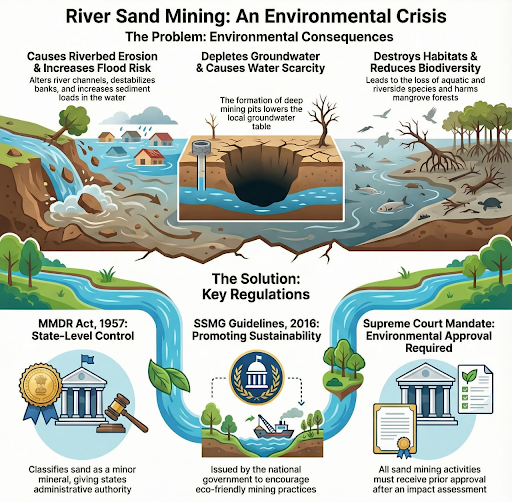

Environmental Impacts of Unscientific Mining

Riverbed and Bank Destabilization: Excessive sand removal deepens the riverbed, altering water flow and causing severe bank erosion, which destroys farmland and threatens human settlements.

Groundwater Depletion: Riverbed sand, a natural aquifer, filters and stores water that recharges groundwater. Its removal lowers the water table, causing severe scarcity for drinking and irrigation.

Loss of Biodiversity: Sand mining destroys countless aquatic micro-habitats, obliterating nesting and breeding grounds for fish, turtles, and critically endangered species like the Gharial.

Degradation of Water Quality: Mining increases water turbidity, which blocks sunlight and harms aquatic plants. It also releases toxic heavy metals and lowers dissolved oxygen, making the water toxic to aquatic life.

Threat to Infrastructure: Riverbed lowering can weaken the foundations of critical infrastructure like bridges, dams, and embankments, creating a major public safety risk.

Socio-Economic Consequences

Massive Revenue Loss: The illegal sand trade is a massive parallel economy, costing state governments thousands of crores yearly in lost royalties and taxes.

Rise of Criminal Syndicates (Sand Mafia): High profits have powered the rise of violent criminal syndicates, who often intimidate or attack officials, activists, journalists, and local communities.

Disruption of Local Livelihoods: Environmental damage directly impacts river-dependent communities: fishermen lose catches, and farmers suffer from water scarcity and fertile land erosion.

|

Legal and Regulatory Framework |

|

|

Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act 1957 |

The primary mining law, allows states to regulate minor minerals (like sand) and create rules against illegal mining and transport. |

|

Deepak Kumar vs. State of Haryana (Supreme Court) |

Made Environmental Clearance (EC) mandatory for all mining leases, including minor minerals in areas under 5 hectares. |

|

Sustainable Sand Mining Management Guidelines (SSMG) |

The MoEFCC requires a District Survey Report (DSR) to scientifically assess sand availability and replenishment before auctioning mining leases. |

|

Enforcement & Monitoring Guidelines for Sand Mining (EMGSM) |

MoEFCC introduced measures for better enforcement, including technology like drones, vehicle GPS tracking, and transparent online sand sales portals. |

Lack of Political and Administrative Will: A strong nexus between illegal miners, politicians, and local officials often undermines enforcement.

Inadequate Monitoring: Despite guidelines, the on-ground adoption of technology for surveillance is weak, making it easy for illegal operations to go unchecked.

Unscientific District Survey Reports (DSRs): DSRs, which form the basis of legal mining, are often prepared without proper scientific study of river sediment and replenishment rates, rendering them ineffective.

Pervasive Corruption: Corruption at various levels allows the illegal mining network to operate with impunity, leading to significant revenue leakage.

Mandatory Technology Integration: States must fully implement the EMGSM 2020 guidelines, making GPS tracking of sand-transport vehicles and drone-based surveillance of mining sites a non-negotiable condition.

Accountability of Officials: As highlighted by the NGT, District Magistrates and Superintendents of Police must be held accountable for lapses in enforcement within their jurisdictions.

Promoting Sustainable Alternatives

Scientific Assessment and Public Participation

Illegal sand mining is a governance and environmental challenge that requires diligent enforcement, technological monitoring, and a shift towards sustainable alternatives to treat sand as a strategic natural resource.

Source: DOWNTOEARTH

|

PRACTICE QUESTION Q. Despite a comprehensive legal framework, illegal sand mining remains a persistent challenge in India. Critically analyze. 150 words |

Sand is classified as a 'minor mineral' under the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957. This classification is generally for minerals that are of lower economic value compared to 'major minerals' like iron ore or coal, and whose regulation is delegated to state governments to manage based on local conditions.

The sand in a riverbed acts as a natural porous aquifer that holds water and allows it to percolate downwards, recharging the groundwater table. When this sand is excessively removed, the riverbed deepens, and this natural aquifer is destroyed, leading to a significant lowering of the water table in surrounding areas.

A District Survey Report (DSR) is a mandatory scientific document introduced by the Sustainable Sand Mining Management Guidelines, 2016. Its purpose is to comprehensively assess the availability of sand in a district's rivers, its rate of replenishment, and the environmental impact of mining. Mining leases are supposed to be granted only after a robust DSR is prepared.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved