The 93rd Constitutional Amendment Act addresses deepening inequality in private educational institutions by extending affirmative action. However, it faces challenges due to institutional autonomy and meritocracy vs the state's obligation to ensure social equity. A modern India must balance legislation, financial support, and monitoring mechanisms for an equitable education system.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: INDIAN EXPRESS

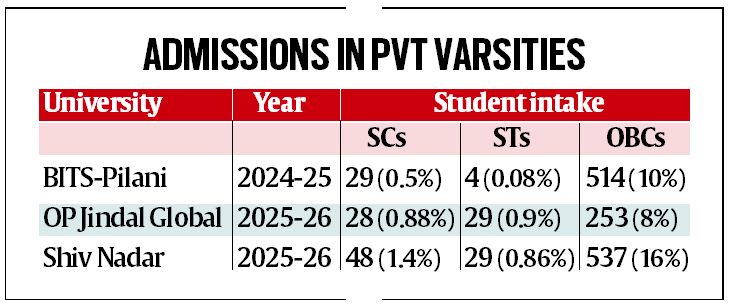

The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Education recommended 27%, 15% and 7.5% reservation for OBC, SC and ST students, respectively, in private higher education institutions.

|

RESERVATION SYSTEM IN INDIA: MEANING, OBJECTIVES, CHALLENGES AND WAY FORWARD |

The 93rd Amendment Act (2005) empowered Parliament to extend caste-based quotas to private colleges and universities.

No separate national law has been enacted, so private universities remain outside mandatory reservation unless states legislate.

The Supreme Court declared that reservation in private colleges is constitutionally valid if backed by law.

In P.A. Inamdar vs Maharashtra (2005): Court ruled that non-minority unaided private educational institutions were not obligated to follow state-mandated reservation policies in admissions.

Ashok Kumar Thakur vs Union of India (2008) and Indian Medical Association vs Union of India (2011) upheld OBC reservation in unaided institutions once authorized by law.

Pramati Educational and Cultural Trust vs Union of India (2014) restated that Article 15(5) is “constitutional and permissible”.

The Supreme Court upheld the 103rd Amendment (EWS quota) in private colleges, indicating that economic reservations can also be applied.

Rapid private expansion: Private universities grew from 276 in 2015 to 523 by 2024, and now enroll about a quarter of all students (26% of total enrolment in 2021–22).

Deep underrepresentation: Marginalized groups are underrepresented in private campuses. For example, the Department of Higher Education said that about 40% of students at private HEIs are OBC, 14.9% are SC and 5% are ST.

Systemic inequality: Many disadvantaged students attend overcrowded or underfunded public colleges due to high fee structure in private college.

|

State level Intervention |

|

|

State |

Private College Policy |

|

Tamil Nadu |

7.5% horizontal quota for Government-school students applies within the State/government quota in private medical colleges. Clearly codifies reservations in private unaided non-minority colleges. |

|

Kerala |

Reservation applies on “surrendered/government” seats in private self-financing colleges (engineering/medical); by Commissioner for Entrance Examinations (CEE). |

|

Karnataka |

Reservation policy on seats surrendered to the government by private unaided colleges.. |

|

Andhra Pradesh |

SC (15%), ST (6%), BC (25%) reservations applicable to seats in private unaided non-minority institutions. Clearly codifies reservations in private unaided non-minority colleges. |

|

Maharashtra |

Proposals on EWS/private medical quotas reversed by Court; reports of cuts in quota share at private unaided MBBS sparked protests. |

In August 2025, a Parliamentary Standing Committee (Education) recommended enacting a law to mandate quotas in private universities.

The committee called for 27% OBC, 15% SC, and 7.5% ST reservations in private higher education, matching norms in public institutions.

It mentioned Article 15(5) and Supreme Court rulings (IMA and Pramati) to stress that such quotas are constitutionally allowed.

It proposed the financial model: any reserved seats in private colleges must be “fully covered” by government funding, similar to the 25% school quota under Right To Education Act.

It urged creating dedicated government funds to expand seats, hire faculty, and improve infrastructure in colleges implementing reservations – ensuring general seats are not cut.

Financial burden: Private colleges charge high fees, and quotas would mean either revenue loss or the need for government subsidies. Without clear funding, they cannot maintain quality or may freeze seats.

Institutional autonomy: Mandatory quotas violate on private management rights. This already led to legal battles (e.g. minority-run colleges claiming Article 30 rights to avoid reservations).

Implementation complexity: Rolling out quotas requires administrative changes (revising admission forms, outreach to candidates, entrance exam adjustments) and support systems (remedial classes, financial aid).

Political resistance: Reservation policy is politically sensitive. Any move to extend quotas can face opposition or be delayed in the “intermediate space” of politics.

Data and accountability: Without a law or clear mechanism, there is currently no consistent tracking of caste data in private institutions.

|

What is the "Creamy Layer" Debate? The "creamy layer" refers to the relatively affluent and advanced members of a backward class who are deemed capable of competing without reservation. Origin: The Supreme Court introduced this concept in the Indra Sawhney case (1992), mandating that the creamy layer within the OBCs must be excluded from the benefits of the 27% quota. Criteria for determining the creamy layer

Current Debate: Extending this principle to SCs and STs reservation

|

Brazil (Racial/Economic quotas): Since 2012, Brazil requires that at least half of seats in public universities be reserved for students from disadvantaged racial or low-income backgrounds.

Europe and UK (Equality policies): Most Western countries prohibit quotas by law but impose strong anti-discrimination rules.

Malaysia (Bumiputra policies): Reserves spots in public universities and certain private institutions for Bumiputra (ethnic Malay) students, with scholarships.

South Africa (B-BBEE and quotas): South Africa’s Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (B-BBEE) policy enforces racial inclusion in higher education, but there is no special constitution-based quota for students. Universities voluntarily set race-based enrollment goals.

These examples show that few democracies mandate quotas in fully private education; many use public law and provide incentives or market adjustments.

Enact National Legislation: Parliament should pass a law under Article 15(5) to formalize quotas in private higher education.

Ensure Funding and Incentives: Government must finance the expansion of reserved seats so private colleges do not cut general seats. The RTE school model suggests reimbursing fees for quota students.

Strengthen Public Institutions: Parallel investment in government colleges, to improve public university capacity and quality, provides alternatives for disadvantaged students and prevents overreliance on private slots.

Mandate Scholarships and Support: Private colleges should provide freeships or scholarships to reserved-category students and possibly preparatory courses. This lowers the financial barrier for quota admits.

Data and Oversight: Establish a monitoring mechanism to collect and publish demographic data on private college students. Regular audits would track progress and enforce compliance, help adjust policies over time.

Phased Implementation: A gradual rollout (for example, initial focus on OBC or professional courses) could ease the transition. Pilot scheme in select institutions before full scale-up.

Build Political Consensus: Politicians and stakeholders must openly discuss the benefits of inclusive education. Civil society and student groups can raise awareness of the justice rationale.

By combining legislative action with financial planning and capacity building, India can extend the promise of social justice to private campuses. Ensuring reserved seats do not come at the cost of educational quality or general seats. A data-driven, phased approach under strong political will can help realize the constitutional vision of equal opportunity for all.

Source: INDIAN EXPRESS

|

PRACTICE QUESTION Q. Reservation in private institutions is not a matter of charity but a constitutional mandate for social justice. Critically analyze. 250 words |

It empowers the state to provide reservations for SCs, STs, and OBCs in all educational institutions, including private unaided ones, except minority institutions.

The 93rd Constitutional Amendment Act, 2005, which added Article 15(5), provides the state with the power to make laws for reservations in private educational institutions.

A 2002 Supreme Court judgment that declared private unaided educational institutions have the autonomy to manage their own admissions, prompting the government to introduce Article 15(5) to overcome this ruling.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved