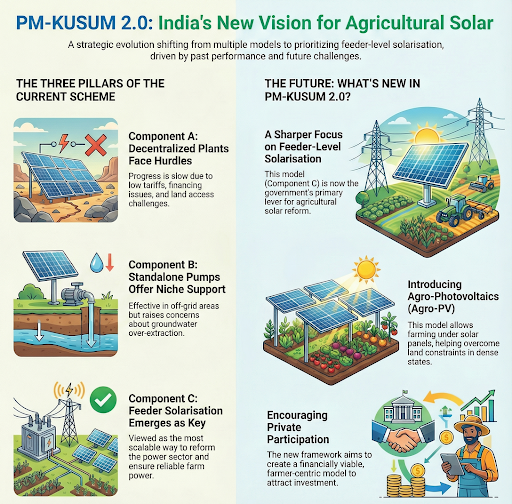

The Union Government plans to roll out PM-KUSUM 2.0, shifting from pump replacement to feeder-level solarisation. By promoting Agro-PV and using the Agri Infrastructure Fund, it tackles land and credit constraints, enables farmers as energy producers, and ensures reliable daytime power, transforming rural energy security.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: DOWNTOEARTH

The Union government is preparing to roll out PM-KUSUM 2.0, a successor to the PM-KUSUM scheme, to continue the push for decentralised solar in agriculture.

The PM-KUSUM scheme was launched by the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) in 2019.

It aims to ensure energy security for farmers, align with India’s climate commitments, and transform them from food providers ('Annadata') to energy providers ('Urjadata').

Due to implementation delays caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the scheme's timeline has been extended to March 31, 2026.

The scheme targets the addition of 34,800 MW of solar capacity with a total central financial support of ₹34,422 crore.

Objectives of the scheme

Key Components of PM-KUSUM

The scheme has three components, each addressing a different aspect of agricultural energy use.

Financial Support & Subsidies

The government provides financial assistance to make these systems affordable:

Major Benefits

Focus on Feeder-Level Solarization

The next phase is expected to focus on Feeder Level Solarization (FLS) as the main scalable model for agricultural solarization, unlike the original scheme's multiple components.

Agro-photovoltaics (Agro-PV)

To combat land shortages, the government is exploring models for cultivation under elevated solar panels, allowing farmers to produce power while keeping land cultivable.

Integration of Energy Storage

Adding energy storage for stable power during non-solar hours is a potential future design change, but will likely increase capital expenditure.

Ease of Financing

Proposals aim to bring decentralized projects under the Agri Infrastructure Fund for farmers to access easier concessional credit and reduce high upfront margin money.

Administrative Simplification

A single national portal is being considered for the scheme to simplify applications and lessen reliance on diverse state-level implementation.

Financial Barriers

High Upfront Costs: Even with 60% combined subsidies from the Centre and States, the remaining 10%–40% initial investment is a significant barrier for small and marginal farmers.

Limited Credit Access: Farmers often struggle to secure bank loans due to collateral requirements and high margin money demands.

Tariff Viability: In Component A, low solar tariffs discovered in tenders are often unviable for developers and farmers after factoring in land and financing costs.

Cheap Grid Electricity: Heavily subsidized or free electricity for agriculture in many states reduces the financial incentive for farmers to switch to solar pumps.

Technical and Logistical Issues

Land Availability: Setting up decentralized plants requires land within five kilometers of a substation to minimize transmission losses, which is scarce in densely cultivated regions.

Domestic Content Requirement (DCR): Strict rules for using locally manufactured solar cells have led to higher costs and supply shortages compared to non-DCR modules.

Grid Integration: Issues such as inadequate substation capacity, voltage fluctuations, and frequent feeder trippings reduce the efficiency of grid-connected systems.

Maintenance Gaps: A lack of standardized after-sales service and trained technicians in rural areas hampers the long-term functionality of installed systems.

Operational and Administrative Challenges

Slow Discom Payments: Delays in payments from financially stressed distribution companies (discoms) for surplus power discourage participation in grid-connected components.

Procedural Delays: Long wait times for land conversion, Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs), and other regulatory approvals have slowed progress.

Environmental Risks: Without proper demand-side management, standalone solar pumps (Component B) may lead to over-extraction of groundwater because operational costs are zero.

Regional Disparities: Implementation is uneven, with states like Haryana and Rajasthan outperforming others due to better infrastructure and local agency coordination.

Comprehensive DISCOM Reforms: Linking scheme funds to mandatory, time-bound reforms in state DISCOMs is crucial to ensure financial viability and payment security for developers.

Integrated Policy Approach: PM-KUSUM must be linked with schemes for water conservation, like the Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana (PMKSY), to promote micro-irrigation and prevent groundwater depletion.

Streamlining Processes: States should establish single-window clearance mechanisms for land acquisition, grid connectivity, and power purchase agreement (PPA) approvals to fast-track projects.

Empowering Farmer Collectives: Promoting Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) and cooperatives to develop and manage solar projects will ensure greater community ownership and benefits.

PM-KUSUM, through Feeder-Level Solarisation and improved DISCOM health/inter-agency coordination, can revolutionize agriculture and the energy sector, promoting farmer welfare, energy security, and climate goals.

Source: DOWNTOEARTH

|

PRACTICE QUESTION Q. The term 'Agro-Photovoltaics (Agro-PV)', often seen in the news in the context of renewable energy, refers to: A) A technology for converting agricultural waste into electricity. B) The practice of using the same parcel of land for both solar power generation and agriculture. C) A specialised solar panel designed to power cold storage facilities. D) A government subsidy scheme for farmers to purchase photovoltaic cells. Answer: B Explanation: Agro-Photovoltaics (Agro-PV), also known as agrivoltaics or dual-use solar, is an innovative system designed to maximize land use efficiency by integrating agricultural activities with solar energy generation on the same plot of land. |

PM-KUSUM (Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha evam Utthaan Mahabhiyan) is a scheme by the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy launched in 2019 to provide energy security to farmers and de-dieselise the agriculture sector. It has three components for setting up solar plants, installing solar pumps, and solarising existing grid-connected pumps.

FLS is a model where a dedicated solar power plant is set up to supply power to a specific agricultural feeder (a power line exclusively for farm pumps). It is considered more efficient and scalable than solarising millions of individual pumps and offers benefits to farmers, DISCOMs, and the environment.

Agro-Photovoltaics is an innovative practice of using the same piece of land for both agriculture and solar energy generation. It involves cultivating crops under elevated solar panels, which can improve crop yields, reduce water evaporation, and provide farmers with two separate income streams from the same land.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved