India’s rural waste crisis reflects rising consumption, weak infrastructure, and poor data. Evidence from Murud shows top-down fixes fail amid local complexity. Success, as in Korlai, needs strong local leadership and community ownership. Empowering Gram Panchayats, decentralised models, and reforming ineffective EPR financing are essential for sustainable solutions.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: DOWNTOEARTH

Waste crisis is a silent and widespread problem in villages where improper rural waste management remains a severe risk to public health and the environment.

Solid Waste Generation

India generates approximately 1,70,338 tonnes per day (TPD) of solid waste. Urban areas are projected to generate 165 million tonnes of waste annually by 2030. (Source: PIB)

Inadequate Processing

Only about 79% of the municipal solid waste generated is processed, leaving a daily deficit of over 30,000 tonnes that ends up in landfills. The remaining waste often accumulates in over 3,000 landfills across the country. (Source: Centre for Science and Environment, 2024)

Plastic Waste

India is identified as the world's largest plastic polluter, emitting roughly 9.3 million tonnes of plastic waste into the environment annually. Around 5.8 million tonnes of plastic are burned openly each year, contributing heavily to air pollution. (Source: Nature)

E-Waste Surge

India is the world's third-largest e-waste producer. E-waste generation nearly doubled from 7.08 lakh tonnes in 2017-18 to 13.98 lakh tonnes in 2024-25. (Source: CPCB, 2025).

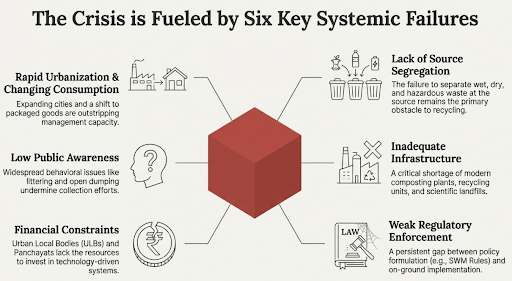

Rapid Urbanization: As cities grow, their existing waste management infrastructure becomes overburdened.

Changing Consumption Patterns: Increased use of packaged goods and disposable products has led to more complex and non-biodegradable waste streams.

Lack of Source Segregation: The failure of households and businesses to separate wet, dry, and hazardous waste at the source is a primary obstacle to effective recycling and processing.

Inadequate Infrastructure: There is a severe shortage of modern waste processing facilities, including composting plants, recycling units, and scientific landfills.

Weak Regulatory Enforcement: Gaps between policy formulation and on-ground implementation, coupled with a lack of accountability at the municipal level, hinder progress.

Financial Constraints: Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) lack the financial resources to invest in and operate modern, technology-driven waste management systems.

Low Public Awareness: A general lack of public participation and behavioral issues like littering and open dumping exacerbate the problem.

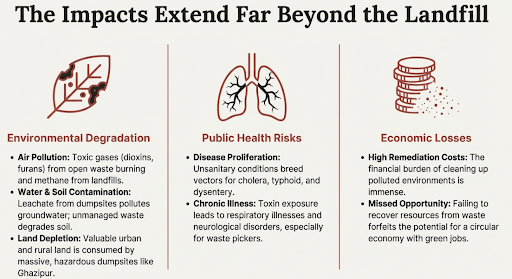

Environmental Degradation:

Public Health Risks:

Economic Losses:

Aims to make all cities 'Garbage Free'. Focuses on 100% source segregation, scientific processing of all municipal solid waste, and remediation of legacy dumpsites.

Solid Waste Management (SWM) Rules, 2016

Mandates waste segregation at source into three streams: biodegradable, non-biodegradable, and domestic hazardous waste. Extends rules beyond municipal areas to cover urban agglomerations and industrial townships.

Plastic Waste Management (PWM) Rules, 2016 (and amendments)

Introduced and strengthened the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) concept. Phased out single-use plastics and increased the minimum thickness of plastic carry bags to 120 microns. The 2024 amendment tightens rules for biodegradable plastics, mandating they leave no microplastics.

E-Waste (Management) Rules, 2022

Mandates scientific disposal and recycling of e-waste. Sets specific collection and recycling targets for producers (60% for 2023-25, rising to 80% by 2027-28) under the EPR framework.

(Galvanizing Organic Bio-Agro Resources Dhan) Aims to convert cattle dung and organic waste into biogas and compost.

Lack of Community Participation & Behavioural Change

Weak Political Will & Local Governance

Effective Solid Waste Management (SWM) depends on proactive local leadership and strict compliance enforcement by the Gram Panchayat, as illustrated by a Murud village case study.

|

Korlai Village (Successful Model) |

Kashid Village (Struggling Model) |

|

|

Leadership |

Proactive Sarpanch who took a firm stance and involved women's groups. |

Gram Panchayat shows inaction, caught between political pressures and its mandate. |

|

Enforcement |

Announced and enforced a fine of ₹1,000 for dumping/burning waste, with a reward for whistleblowers. |

Refusal by powerful local actors (e.g., beach stall owners) to segregate waste goes unchecked. |

|

Outcome |

Within six months, almost all households achieved consistent waste segregation. |

Continued open dumping and burning of waste, including a major fire at a dumpsite in February 2024. |

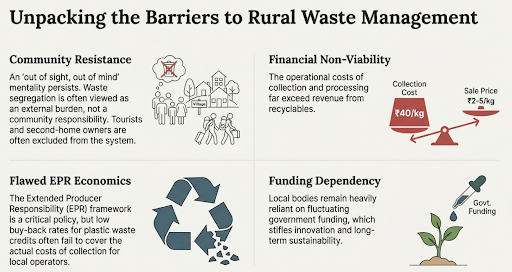

Financial Non-Viability

Enforce Source Segregation: Make waste segregation mandatory at the household and commercial level through a mix of incentives and penalties.

Promote a Circular Economy: Shift focus from disposal to a "Reduce, Reuse, Recycle" model. Strengthen the EPR framework to ensure producers actively participate in creating a circular supply chain.

Decentralize Waste Processing: Encourage community-level composting, biogas plants, and local material recovery facilities to reduce the burden on centralized landfills.

Invest in Technology: Adopt modern technologies for waste-to-energy conversion, automated sorting, and smart waste management (e.g., IoT-enabled bins and GPS-tracked collection vehicles).

Formalize the Informal Sector: Integrate waste pickers into the formal waste management chain, ensuring their safety, providing social security, and leveraging their expertise.

Strengthen Local Governance: Empower Gram Panchayats with the funds, functions, and functionaries to enforce SWM rules, impose user fees (Swachhata Shulk), and create local bye-laws.

Promote Community-Led Models: Involve Self-Help Groups (SHGs), especially women, in waste collection and management activities. This not only ensures community ownership but also creates local livelihoods.

Promote on 'Waste to Wealth' Models: Integrate SWM with other government schemes: link composting to organic farming, and use GOBAR-Dhan to convert cattle dung and organic waste into biogas and bio-slurry.

Intensive Behaviour Change Communication (BCC): Conduct sustained awareness campaigns through schools, Gram Sabhas, and local events to build a shared sense of responsibility for waste management.

Learn from Global Best Practices

Addressing the waste crisis requires bridging gaps in implementation, infrastructure, and public participation through a circular economy, empowered local bodies, and behavioral change for a 'Garbage Free' future.

Source: DOWNTOEARTH

|

PRACTICE QUESTION Q. The success of the Swachh Bharat Mission in rural India is hindered more by behavioral and structural barriers than by a lack of policy. Discuss. (250 words) |

SWM systems fail due to a combination of factors: weak political will from local leaders, a lack of community ownership and responsibility, the ineffectiveness of 'one-size-fits-all' solutions, and a significant financial gap where operational costs far exceed returns from selling waste.

The Gram Panchayat, particularly a committed Sarpanch, plays a critical and decisive role. As seen in the Korlai village example, a strong local leader who is willing to enforce rules, impose fines, and drive community participation can ensure the success of a waste management system where others fail.

'ODF Plus' is the next step after a village becomes Open Defecation Free (ODF). It focuses on sustaining the ODF status while also ensuring comprehensive management of both solid and liquid waste, aiming for visually clean villages.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved