The press in India has played a pivotal role from the freedom struggle to the modern democratic era. During colonial times, newspapers shaped nationalist consciousness, mobilized masses, and exposed British policies despite severe censorship. After Independence, the press expanded with constitutional protections, institutional reforms like the PCI, and growing diversity across languages and mediums. Today, the media continues to be essential for transparency and accountability but faces challenges such as misinformation, political pressure, commercialization, and threats to journalist safety. A strong, ethical, and independent press remains vital for sustaining India’s democracy.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: PIB

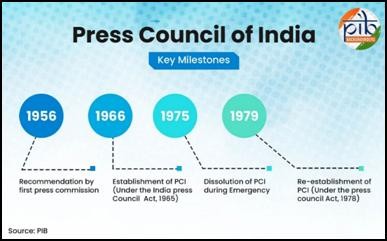

National Press Day, observed on 16 November, commemorates the establishment of the Press Council of India (PCI) and celebrates the crucial role of a free and responsible press in sustaining democracy. The day recognizes the media’s function as the fourth pillar of democracy, shaping public opinion, promoting transparency, and holding power accountable.

|

Must Read: PRESS FREEDOM | WORLD PRESS FREEDOM INDEX | INDEPENDENCE OF THE PRESS IN INDIA | |

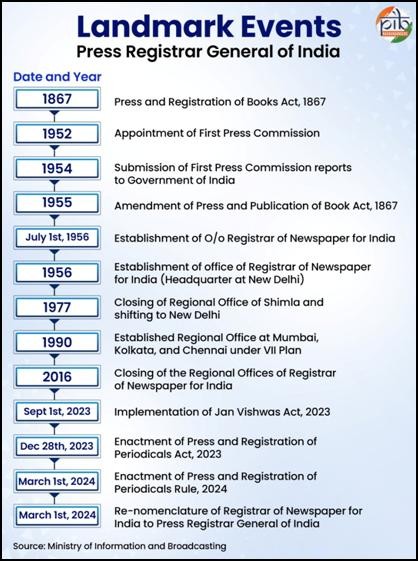

India’s media sector has expanded significantly, with registered publications rising from 60,143 in 2004–05 to 1.54 lakh in 2024–25.

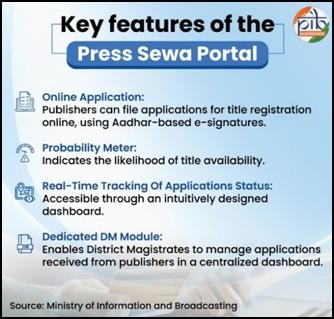

Press and Registration of Periodicals (PRP) Act 2023 and the Press Sewa Portal, have digitized and streamlined periodical registration, onboarded 40,000 publishers, and registered 3,000 printing presses within six months, enhancing ease of doing business.

Picture Courtesy: PIB

Instrument in political awakening: The press transformed scattered grievances into a shared national cause. Through editorials, pamphlets, and journals, it explained colonial policies, exposed injustices, and articulated the idea of Swaraj. It educated ordinary Indians about their rights and responsibilities, nurturing an informed citizenry capable of resisting colonial rule.

Helps in building identitiy: The press helped create a pan-Indian identity that transcended linguistic, regional, and social divisions. Newspapers like Kesari, Amrita Bazar Patrika, The Hindu, and Bengalee became platforms for nationalist ideas, uniting people under common symbols, shared history, and collective aspirations.

Helps in ideological exchange: The freedom struggle was not monolithic. Moderate, extremist, Gandhian, socialist, and revolutionary viewpoints all found expression in the press. This open debate sharpened political strategies, helped refine national goals, and allowed ideas to circulate even under censorship.

Social reform and mobilisation: Beyond political independence, the press challenged social evils—untouchability, illiteracy, child marriage, gender inequality—helping prepare society for nationhood. Reformers like Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Jyotiba Phule, and others used newspapers to shape progressive opinion and mobilize communities for change.

Exposing colonial exploitation: The vernacular press systematically revealed economic drain, oppressive laws, racial discrimination, and atrocities committed by British administration. These revelations created moral pressure on the colonial state and strengthened the legitimacy of national resistance.

Non-Cooperation and mass movements: During Gandhian movements, the press became a powerful tool for inspiring collective action. Newspapers publicized programmes of non-cooperation, civil disobedience, Swadeshi, boycott, and constructive work. They transformed local protests into nationwide campaigns.

Link between leaders and the masses: Newspapers served as the bridge between national leaders and the public. They carried speeches, resolutions, Congress debates, and Gandhiji’s weekly messages in Young India and Harijan, making politics participatory and accessible.

Internationalising India’s struggle: Indian and foreign journals publicized the freedom struggle globally—highlighting issues like the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, salt satyagraha, and civil liberties violations. International pressure added moral weight to India’s cause.

Press as a threat for Britishers: The British increasingly saw newspapers as catalysts of political agitation. With the rise of vernacular publications reaching rural populations, the press became a mass-based challenge to colonial authority. The state thus considered it necessary to regulate, monitor, and suppress newspapers perceived as “seditious.”

Legislation to control expression

To contain nationalist ideas, the British enacted a series of laws designed to curb freedom of the press:

Imposing censorships: The British set up mechanisms to closely monitor nationalist writings. Editors, reporters, and printing presses were placed under watch. Pre-censorship was imposed during periods of unrest, especially after the 1857 Revolt, during the Swadeshi movement, and again during World War I and II. Police report routinely documented “seditious” articles, and newspapers were required to submit copies for official scrutiny.

Frequent prosecution: Editors, journalists, and owners were frequently prosecuted under sedition laws (e.g., Section 124A of IPC). Heavy fines, imprisonment, and confiscation of printing presses became common tools of intimidation. Many nationalist publications survived only through public donations and solidarity campaigns.

Attempt to divide the press: Along with repression, the colonial state attempted softer strategies—supporting loyalist newspapers, offering subsidies and advertisements, and encouraging publications that praised British rule. This created a landscape where pro-establishment press coexisted with the nationalist press, each battling for influence.

Transition from colonial control to constitutional freedom: After Independence, the press moved from a climate of restrictive colonial laws to a framework grounded in constitutional guarantees.

Nation-Building and Developmental Orientation (1950s–60s): In the early decades, the press adopted a development-oriented and nation-building role, acted as a bridge between the government and citizens in disseminating development plans.

Press Regulation, the First Amendment & Parliamentary Debates: Concerns over public order led to First Constitutional Amendment (1951) introducing “reasonable restrictions.” The 1950s saw debates on press control vs. press freedom with key court judgments like Romesh Thappar and Brij Bhushan. This formed the foundational jurisprudence on press liberty.

Expansion of Print Media & Rise of Vernacular Press (1960s–80s): The spread of literacy, cheaper printing technology, and political mobilization led to a major rise of regional and vernacular newspapers. Press became more mass-based, accessible, and politically impactful.

Liberalization & Emergence of Private Media (1990s onwards): Economic reforms transformed media explosion of private television channels, 24×7 news cycles, and corporatized media houses.

Picture Courtesy: PIB

Picture Courtesy: PIB

Legal and Welfare Framework

Picture Courtesy: PIB

Awards and Recognition: National Press Day also honours excellence in journalism through awards like the Raja Ram Mohan Roy Award, highlighting exemplary contributions across print media.

The press in India has evolved into a vital pillar of democracy, expanding from limited post-Independence coverage to today’s diverse print, broadcast, and digital ecosystem. Despite challenges such as commercialization, misinformation, and political pressure, it continues to play a key role in informing citizens, safeguarding accountability, and strengthening democratic institutions. Ensuring freedom, ethical standards, and technological adaptation remains essential for its credibility and effectiveness in the future.

Source: PIB

|

Practice Question Q. Discuss the role of the press in India’s freedom struggle. How has the nature of press freedom evolved in the post-Independence period? (250 words) |

Because it acts as a watchdog over the government, informs citizens, shapes public opinion, and enables accountability, thereby strengthening democratic functioning.

No. The Constitution does not explicitly mention “freedom of press,” but it is implicitly protected under Article 19(1)(a) – Freedom of Speech and Expression.

The PCI is a statutory body that maintains ethical standards in journalism, protects press freedom, and addresses complaints against the press. However, it has advisory powers, not punitive ones.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved