Judiciary is integrating AI for efficient, transparent, and accessible justice. Initiatives like SUPACE and SUVAS help judges with research and translation. However, AI presents ethical challenges like data privacy and algorithmic bias. A human-centric approach is crucial for fairness, justice, and accountability.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: THE HINDU

The Kerala High Court has become the first court in India to set guidelines for the use of AI tools in judiciary, restricting them to non-judicial tasks, and mandating human oversight to balance efficiency against the potential for bias and other risks.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the technologies that enable computers to mimic human learning, reasoning and problem-solving. It can analyze data, recognize patterns, translate language and make conclusion.

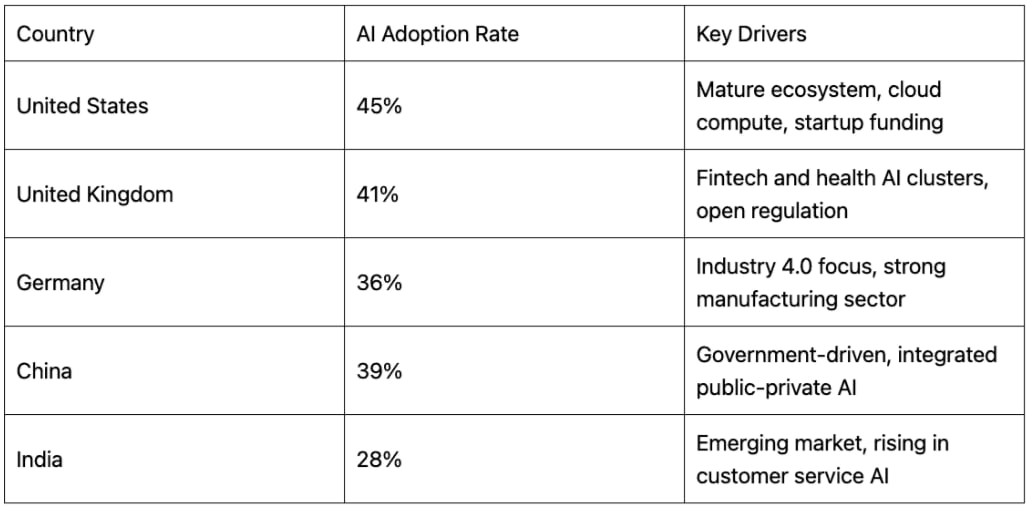

AI adoption is surging worldwide. Over 73% of organizations globally are using or piloting AI in core functions. (TechNation Report)

Global AI market was valued at $391 billion in 2025 and is projected to reach $1.81 trillion by 2030.

AI boosts productivity and decision-making across sectors. In the judiciary it handle routine tasks like sorting documents or translating text, allowing judges to focus on complex legal analysis.

In 2024 UNESCO survey found that about 44% of judicial professionals across 96 countries already use AI tools (e.g. ChatGPT) in work-related tasks, indicating increasing potential.

Why Introduce AI in Indian Judiciary?

Why Introduce AI in Indian Judiciary?

Case backlog: Over 82,000 cases in the Supreme Court, more than 62 lakh cases in the High Courts and about 5 crore cases in the lower courts, are pending. (Source: The Hindu)

Efficiency gains: AI can perform legal research (searching precedents, summarizing documents) and case management.

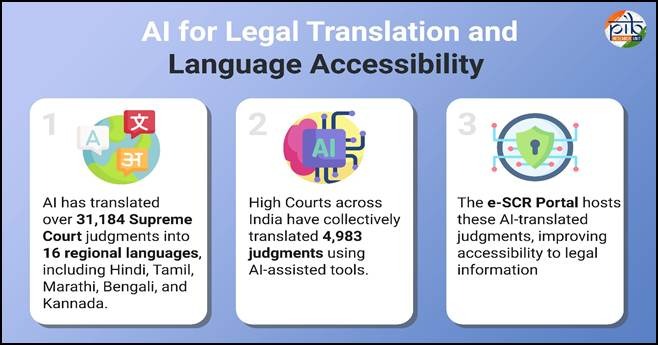

Access & inclusivity: Language barriers have limited many citizens’ access to higher courts.

Equity and outreach: Hybrid court systems (live + virtual) combined with AI (e.g. automated translations) can bring justice closer to disadvantaged populations.

|

Constitutional and Legal Framework Access to justice (Art.14/21): Constitution guarantees equality before law and the right to speedy trial, technologies that ensure legal informations are widely available fulfill these fundamental rights. No AI-specific law yet: Digital Personal Data Protection Act (2023) will govern any automated processing of personal data (relevant for AI use in evidence and records).

India need clear guidelines or rules – such as mandatory disclosure of AI use in filings – now the judiciary relies on internal rules to govern AI in courtrooms. |

eCourts Phase III: Under the National e-Courts project, the government is integrating AI across court systems. Government allocated ₹7,210 crore (2021–2027), with ₹53.57 crore specifically for AI and blockchain innovation.

AI in Supreme Court: In 2021 the SC’s AI Committee launched SUPACE (Supreme Court Portal for Assistance in Court Efficiency) to help judges analyze case files using AI.

High Courts: Several High Courts have set up AI committees and training programs.

|

Kerala High Court July 2025 AI Guidelines Promote AI Literacy: Judges, lawyers, and court staff require comprehensive training on how to use AI tools and their inherent limitations.

Establish Clear Usage Guidelines: Litigants have the right to be informed if AI is being used in the adjudication of their case or within a specific courtroom.

Develop Technical Support Systems: As recommended in the Vision Document for Phase III of the eCourts Project, create dedicated technology offices.

|

Legal research portals: All High Courts have been advised to encourage judges to use SUPACE for legal research.

AI translation in action: Supreme Court judgements translated into up to 18 languages, broadened public access.

Predictive tools: Some courts are experimenting with predictive analytics; analyze past data to advise on litigation strategy.

Bias and fairness: AI systems learn from historical data, which can implant existing biases.

Accountability: Neither litigants nor judges can inspect how an AI arrived at a suggestion. Without transparency, it would be hard to examine an AI-based recommendation.

Inaccuracy in Translation and Transcription: A Supreme Court judge noted an AI tool translated "leave granted" into Hindi as "holiday approved."

Errors and “hallucinations”: Generative AI (like GPT) can fabricate information. CJI B. R. Gavai in the courtroom highlighted a case where AI-based research tools delivered fake case references.

Human element & ethics: Several judges have stressed that core judicial functions demand human empathy and moral judgment, algorithms cannot replace the understanding judges bring to sensitive cases (e.g. family law, juvenile matters).

Privacy and security: AI tools require large datasets (court records, personal details, etc.). Mishandling this data could violate privacy or be a cybersecurity risk.

Access and inequality: Danger of a “two-tiered” justice system. Experts warned that if AI benefits only the well-resourced, the poor could be left with inferior legal help.

|

Ethical Pillers of AI in the Judicial System Fundamental Rights: AI use in the judiciary must uphold fundamental rights like the Right to Privacy and the right to a fair trial.

Equal Treatment: AI trained on biased historical data could discriminate based on caste, gender, or socioeconomic status.

Data security: Using sensitive judicial data requires robust security and adherence to privacy laws to prevent breaches. Transparency: AI systems must be transparent to build trust and ensure accountability. Explainability allows stakeholders to understand how AI reaches a conclusion. |

Build judicial capacity: Judges, lawyers and court staff need training in AI literacy. Integrate AI modules in judicial academies and programs.

Establish clear guidelines: Courts and legislatures should set clear rules for AI use.

Strengthen data safeguards: Any AI deployment must comply with privacy laws (now DPDP Act) and use secure infrastructure. Government already invests in cyber-security for courts; these efforts should expand to AI.

Phased, supervised adoption: Introduce AI phase wise, starting with low-risk tasks (e.g. legal search, translation) and always under human review, judges must “approve” any AI-generated finding.

International cooperation and standards: India should participate in global AI-in-justice initiatives.

Inclusivity and public engagement: Invest in extending e-court infrastructure to all states and smaller courts. Official AI portals should provide public updates on AI use in courts.

What India can learn from other countries?

AI offers a powerful toolkit to modernize courts – potential to transform the “slow-moving” court system into a more efficient, future-ready justice delivery mechanism. However, as CJI Gavai cautioned, AI must serve as an aid, not a replacement for human judges. Every AI-generated insight or draft must be checked and owned by a qualified jurist.

Source: THE HINDU

|

PRACTICE QUESTION Q. The application of Artificial Intelligence in the judiciary promises to address the problem of case backlog and enhance access to justice. Critically analyze. 250 words |

It is the use of AI to forecast judicial outcomes, such as the likelihood of bail, based on historical case data.

It is the risk of AI systems perpetuating existing societal biases present in historical legal data, leading to unfair outcomes.

Some High Courts, like Punjab & Haryana, have experimented with AI chatbots like ChatGPT for research purposes, though not for judgments.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved