Particulate Matter, especially the ultrafine PM1 fraction, has emerged as a major public-health concern in India due to its ability to penetrate deep into the lungs, enter the bloodstream and carry highly toxic metals and reactive chemicals. Studies show PM1 is more harmful than PM2.5, yet it remains unmonitored in India’s regulatory framework, creating a significant data and policy blind spot. Research from Delhi reveals PM1 is often underestimated by nearly 20%, masking true exposure levels during severe pollution episodes. The implications are extensive—rising cardiovascular and child-health risks, high indoor infiltration, delayed policy action, and strong climate linkages through black carbon. While India has launched multiple initiatives such as NCAP, GRAP, BS-VI norms, PMUY and stubble-management schemes to curb PM pollution, the absence of PM1 standards limits their effectiveness. Integrating PM1 into national monitoring, regulation and health studies is now essential for comprehensive air-quality governance.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: Down to Earth

PM1, smaller than one micron, is a lethal but least understood air pollutant in India’s toxic airspace.

|

Must Read: PM 2.5 Pollution | AIR QUALITY INDEX | Air Pollution | SECONDARY POLLUTANTS | |

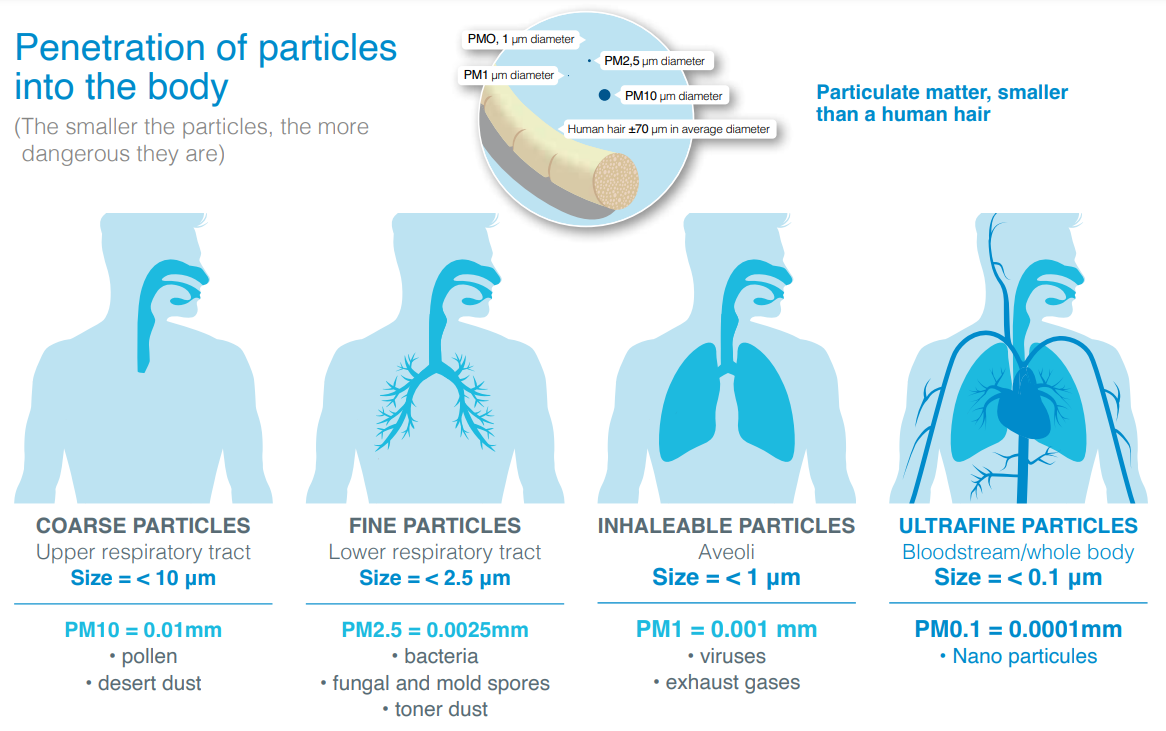

Particulate Matter (PM) refers to a complex mixture of extremely small solid particles and liquid droplets suspended in the air. It is not a single pollutant but a heterogeneous blend of dust, soot, smoke, organic compounds, metals, nitrates, sulphates, and various microscopic aerosols. Because of this diversity, PM behaves both like a pollutant and a carrier of pollutants, influencing air quality, human health, and even climate systems.

PM10 (Coarse Particles)

PM2.5 (Fine Particles)

PM1 (Ultrafine Fine Fraction)

Ultrafine/Nanoparticles

Ultrafine but highly toxic: PM1 (particulate matter <1 micron) is small enough to penetrate alveoli, enter the bloodstream, reach organs, and even cross the blood–brain barrier—a level of infiltration PM2.5 rarely achieves. The Lancet Planetary Health demonstrate that even a small rise in PM1 concentrations is followed by significant increases in hospital emergency visits.

PM1 dominates the fine particulate burden: PM1 forms nearly half of PM2.5 concentrations in many urban environments, reflecting its origin in high-temperature combustion processes such as vehicular exhaust under BS-VI standards, industrial stacks, biomass burning, and recondensed organic or metal vapours.

PM1 drives atmospheric instability and haze formation: Ultrafine particles like PM1 accelerate new particle formation, a key process that rapidly increases the number of airborne particles and contributes to the thick haze typical of winter pollution episodes. Atmospheric studies from China consistently show a strong connection between PM1 growth and the severity of winter smog, highlighting PM1’s role not only as a health hazard but also as an atmospheric destabiliser.

|

CASE STUDY A 2025 study published in Nature revealed that PM1 levels in Delhi are systematically underestimated by around 20 per cent during humid winter mornings, amounting to as much as 50 μg/m³ being missed by current monitoring systems. This underestimation occurs because hygroscopic particles swell in moist air and escape the measurement capabilities of existing instruments, meaning the actual pollution burden is significantly higher than official data suggests. |

Picture Courtesy: AFPRO

Regulatory gap: India lacks formal standards for PM1 under its air quality framework, and neither CPCB nor WHO currently prescribes permissible limits for this fraction. As a result, the national monitoring network (CAAQMS) records only PM10 and PM2.5, leaving PM1 measurements confined largely to short-term academic research campaigns.

Technology gap: Although instruments capable of detecting ultrafine particulate matter exist, they require substantial upgrades, calibration mechanisms and standardisation before they can be deployed at scale. India also lacks BIS-certified technology specifically designed for PM1 monitoring, limiting the feasibility of integrating PM1 into routine measurement systems.

Data and Expertise gap: India currently has limited epidemiological datasets linking PM1 exposure to health outcomes, no comprehensive source-apportionment studies focused on PM1, and insufficient toxicology expertise on ultrafine particles. These scientific gaps make it difficult for policymakers to frame standards or integrate PM1 into regulatory decisions.

Rising health-system burden: PM-exposure remains a leading cause of premature death in India: ambient fine particulate pollution (PM2.5) was associated with roughly 0.98 million premature deaths in India in 2019, making particulate pollution one of the country’s largest environmental health risks.

Indoor exposure risk: Ambient sub-micron particles penetrate buildings efficiently; indoor/outdoor studies and reviews show high infiltration efficiencies for sub-micron particles, meaning that even people who spend most of their time indoors (children, office workers, elderly) remain chronically exposed to urban PM1. This undermines the assumption that indoor spaces reliably shield residents during pollution episodes.

Policy blind spot: India’s national monitoring and regulatory architecture measure PM10 and PM2.5 but does not include PM1 in routine regulatory monitoring or standards, so policy actions (NCAP targets, city GRAP triggers and emergency measures) rely on metrics that systematically under-represent ultrafine risks. This regulatory gap creates delayed or insufficient interventions because the more toxic fraction remains invisible to decision-makers.

Climate-air quality co-benefits and risks: PM1 frequently contains a high fraction of black carbon and combustion-derived organics, components that both harm health and exert strong positive radiative forcing (warming). Because black carbon is a short-lived climate forcer, reducing PM1/black carbon offers fast climate and health gains; conversely, ignoring PM1 forfeits a low-latency mitigation opportunity. International assessments and UNEP/CCAC syntheses emphasise black carbon’s outsized climate forcing and health impacts, making PM1 control a high-value co-benefit target.

|

Category |

Government Initiative |

Key Features |

|

National Air Quality Frameworks |

National Clean Air Programme (NCAP), 2019 |

Targets 40% reduction in PM2.5 & PM10 in 131 non-attainment cities; strengthens monitoring, source apportionment, and city action plans. |

|

National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) |

Sets permissible limits for PM10 & PM2.5; currently under revision to align with WHO guidelines. |

|

|

Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) |

Trigger-based emergency measures in Delhi-NCR to control construction dust, vehicular emissions, brick kilns, and DG sets based on PM2.5/PM10 levels. |

|

|

Monitoring & Data Systems |

CAAQMS Expansion |

1,300+ stations providing real-time PM10 & PM2.5 data; hyperlocal sensor networks being added. |

|

SAFAR (IITM Pune) |

Provides PM forecasts for Delhi, Mumbai, Pune, Ahmedabad; supports early warning systems. |

|

|

Air Quality Index (AQI) |

Public reporting and health advisories centred on PM concentrations. |

|

|

Transport & Mobility Measures |

BS-VI Vehicular Norms |

Reduce vehicular PM emissions by 80–90%; mandate DPFs for diesel vehicles. |

|

FAME I & II (Electric Mobility) |

Promotes e-buses, e-two-wheelers, and charging infrastructure to cut transport PM. |

|

|

Vehicle Scrappage Policy (2021) |

Removes old, high-emitting vehicles to reduce PM emissions. |

|

|

Odd–Even Scheme (Delhi) |

Short-term traffic rationing to temporarily reduce PM peaks during smog episodes. |

|

|

Industrial & Power Sector |

Thermal Power Plant Emission Norms (2015) |

Controls SO₂, NOx & PM emissions; reduces secondary PM2.5 formation via FGD installation. |

|

Zig-Zag Brick Kilns |

Lowers particulate emissions by 50–60% compared to traditional kilns. |

|

|

CEMS (Continuous Emission Monitoring Systems) |

Mandated for polluting industries; tracks stack particulates. |

|

|

Clean Energy & Households |

Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY) |

Provides LPG connections to reduce household PM2.5 & PM1 from biomass burning. |

|

Renewable Energy Expansion (500 GW by 2030) |

Cuts dependence on coal, indirectly lowering PM emissions. |

|

|

Improved Cookstove Programmes |

Low-emission stoves reduce indoor PM by 40–60%. |

|

|

Dust & Construction Control |

Construction & Demolition Waste Rules, 2016 |

Mandate enclosure, dust suppression, recycling, and regulated transport to limit PM10. |

|

Mechanised Road Sweeping |

Reduces road dust, a major PM10 contributor in cities. |

|

|

Agriculture & Biomass Management |

Crop Residue Management Scheme |

Supports Happy Seeder, SMS, balers to prevent stubble burning—a major PM driver. |

|

Pusa Bio-Decomposer (IARI) |

Biological method for in-situ stubble degradation to reduce winter PM spikes. |

|

|

Urban & Green-Cover Initiatives |

Green India Mission (GIM) |

Expands forest cover; captures coarse PM & improves microclimate. |

|

AMRUT & Smart Cities Mission |

Promote urban greenery, non-motorised transport, cool roofs & improved waste systems reducing PM sources. |

|

|

City-Specific Clean Air Action Plans |

Target dust control, industrial zoning, public transport, and local PM mitigation. |

|

|

Waste Management |

Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016 |

Ban open burning of waste, a major PM2.5 source. |

|

Waste-to-Energy & Biomass-to-Energy Projects |

Reduce open dumping/burning and associated PM emissions. |

India’s air pollution control framework is incomplete without PM1.

The science is clear: PM1 is more toxic, more mobile, and more deeply penetrating than PM2.5, yet remains unmeasured. With manageable technological upgrades and strong regulatory intent, India can close this critical data gap, protect public health, and emerge as a global leader in ultrafine particle regulation.

Source: Down to Earth

|

Practice Question Q. “India’s air quality governance remains centred on PM2.5 and PM10, even though PM1 may be more toxic and more harmful.” Examine (250 words) |

Particulate matter refers to a complex mixture of solid particles and liquid droplets suspended in air, varying widely in size, origin, and chemical composition. It includes dust, soot, smoke, metals, organics, and biological particles, making it one of the most harmful components of air pollution.

PM1 consists of particles smaller than 1 micron—far smaller than PM2.5 and PM10—and can penetrate the alveoli, enter the bloodstream, and reach vital organs. It carries more toxic metals and reactive chemicals per unit mass than larger particles.

India does not monitor PM1 because no standards currently exist under CPCB, monitoring technology is not yet certified for regulatory use, and long-term Indian epidemiological evidence is limited. Hence PM1 remains outside the national air-quality framework.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved