Description

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: Indian Express

Context:

India has overtaken China to become the world’s largest rice producer in 2024–25, producing 150 million metric tonnes, compared to China’s 145.28 million tonnes. India now accounts for 28% of global rice production, reflecting steady growth over decades. However, this achievement raises concerns related to water security, crop diversification, fiscal stress, and nutritional outcomes.

Current status of rice production:

- India produced 150.18 million tonnes of rice in the 2024–25 crop year, making it the world’s largest rice producer, surpassing China, which produced 145.28 million tonnes.

- India’s rice exports have been strong. In 2025, exports rose to about 55 million tonnes (second-highest on record), with both basmati and non-basmati categories growing.

- India accounts for roughly 28% of global rice production.

- India and China together produce over half of the world’s rice output, with Bangladesh, Indonesia, Vietnam, Thailand, and other Asian countries also contributing significant volumes.

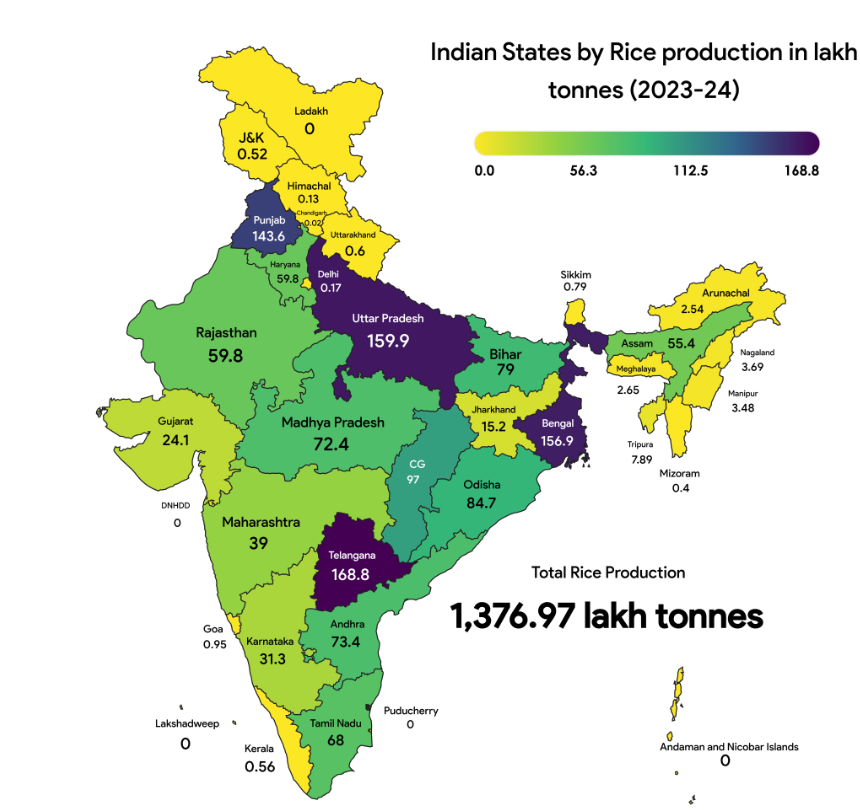

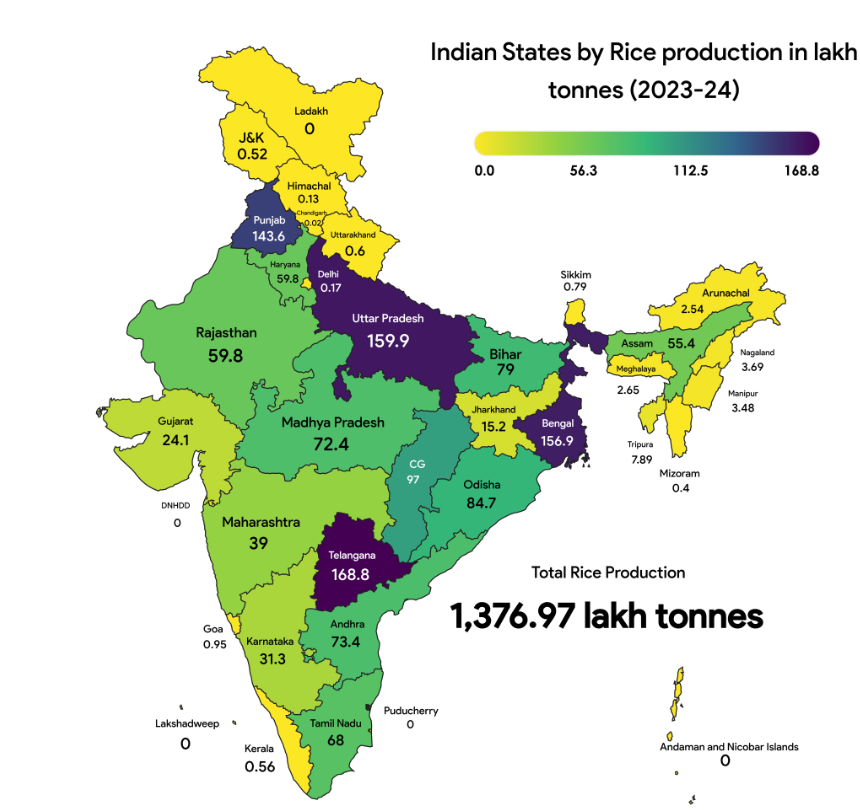

Picture Courtesy: India Data Map

Importance of India’s rice stocks:

- Food security: India’s rice stocks form the backbone of national food security by ensuring uninterrupted supply of foodgrains under the NFSA, PDS, Mid-Day Meal and ICDS schemes, especially during droughts, floods and supply shocks.

- Price stabilisation: Adequate rice stocks enable the government to intervene in markets through mechanisms like the Open Market Sale Scheme (OMSS) to control price volatility and contain food inflation.

- Crisis and disaster management: Large rice reserves provide immediate relief during emergencies such as natural disasters, pandemics and humanitarian crises, thereby strengthening economic and social resilience.

- Farmer income assurance: High rice stocks reflect strong MSP-based procurement, providing assured markets and income stability to paddy farmers, particularly in Punjab, Haryana, Chhattisgarh and Odisha.

- Strategic and geopolitical importance: Surplus rice stocks allow India to remain the world’s largest rice exporter and to regulate exports strategically during global food shortages.

- Support to welfare state: Rice stocks underpin India’s rights-based welfare framework, enabling large-scale food subsidies and effective redistribution to vulnerable populations.

- Policy flexibility: Excess rice stocks provide policy flexibility for ethanol production, animal feed and international food aid, allowing better management of surpluses.

- Associated concerns (Value Addition): While crucial, persistently high rice stocks also lead to high fiscal costs, encourage water-intensive paddy cultivation, and discourage crop diversification, raising environmental sustainability concerns.

Rational behind paddy preference by farmers:

- Assured MSP and procurement: Paddy enjoys the strongest MSP-backed procurement system in India, with the government procuring about 13% of total rice production (2023–24), giving farmers guaranteed price and market assurance.

- Higher and stable returns: At the 2021–22 MSP, paddy generated a net return of ₹56,226 per hectare, significantly higher than maize (₹17,856/ha) and competitive with moong (₹45,665/ha), making it one of the most remunerative crops.

- Wide cultivation and infrastructure support: Paddy is grown in 614 out of ~800 districts and covers about 42 million hectares (2024–25), supported by a dense network of mandis, FCI procurement centres and rice mills.

- Low marketing and price risk: Unlike pulses and oilseeds, paddy farmers face minimal price volatility due to assured procurement, reducing dependence on private traders.

- Heavy input subsidies: Paddy cultivation benefits from subsidised electricity, fertilisers, irrigation and seeds, lowering production risk and costs, especially in states like Punjab and Haryana.

- High and reliable yields: Rice yields are relatively predictable, with Punjab recording ~4,428 kg/ha, Andhra Pradesh ~3,928 kg/ha, compared to the national average of 2,929 kg/ha (2024–25).

- Export demand and global market strength: India is the world’s largest rice exporter, exporting 6 million tonnes of basmati and 13 million tonnes of non-basmati rice in 2024–25, creating sustained domestic demand.

- Weak performance of alternative crops: Other crops show stagnation or decline—for example, cotton yield fell from over 500 kg/ha (2013–14) to ~440 kg/ha (2024–25), making paddy a safer choice.

- Risk aversion of small and marginal farmers: For small farmers, paddy offers a low-risk, high-assurance income option, crucial for livelihood security in the absence of strong procurement for alternatives.

Challenges of Paddy dominance:

- Severe water stress: Paddy is a highly water-intensive crop, requiring about 1–3 tonnes of water to produce 1 kg of rice, leading to groundwater depletion in states like Punjab, Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh.

- Declining groundwater levels: Large-scale paddy cultivation in water-scarce and semi-arid regions has caused over-extraction of aquifers, triggering long-term ecological and health problems.

- Regional yield inequality: Rice productivity varies sharply across states Punjab (4,428 kg/ha) and Andhra Pradesh (3,928 kg/ha) far exceed Bihar (2,561 kg/ha) and Uttar Pradesh (2,824 kg/ha), compared to the national average of 2,929 kg/ha (2024–25).

- Excessive buffer stocks: As of January 1, 2026, India held about 06 million tonnes of rice, far above the buffer norm of 7.61 million tonnes, leading to storage inefficiencies and wastage risks.

- High fiscal burden: The economic cost of rice (procurement, milling, transport and storage) is about ₹33 per kg, translating to ₹1.36 lakh per hectare, excluding power and fertiliser subsidies, straining public finances.

- Environmental degradation: Continuous paddy cultivation contributes to soil nutrient depletion, methane emissions from flooded fields, and stubble burning, worsening climate and air pollution concerns.

- Crowding out crop diversification: Dominance of paddy discourages cultivation of pulses, oilseeds and millets, undermining nutritional security and increasing import dependence for edible oils.

- Policy distortion: Heavy focus on MSP-based procurement of rice creates skewed cropping patterns, weakening market signals for sustainable and climate-resilient crops.

Way Forward:

- Promote crop diversification incentives: Shift from paddy-centric support to direct financial incentives for diversification into pulses, oilseeds and millets, especially in water-stressed and low-yield paddy districts.

- Rationalise MSP and procurement policy: Gradually rebalance MSP and assured procurement by extending effective price support to pulses and oilseeds, while discouraging excessive rice procurement beyond buffer norms.

- Region-specific cropping plans: Adopt agro-climatic and water-based crop planning, encouraging paddy only in high-rainfall and delta regions, and alternative crops in Punjab, Haryana and western UP.

- Water-smart agricultural practices: Promote Direct Seeded Rice (DSR), micro-irrigation, and alternate wetting and drying (AWD) techniques to reduce water use where paddy continues.

- Strengthen value chains for alternative crops: Develop storage, processing, marketing and export infrastructure for pulses, oilseeds and millets to ensure remunerative returns and reduce market risk.

- Link diversification with nutrition goals: Align crop diversification with nutritional security by promoting protein-rich pulses and nutri-cereals, supporting schemes like POSHAN Abhiyaan.

- Use excess rice stock savings productively: Utilise savings from reduced rice procurement (₹1.36 lakh per hectare) to fund diversification incentives, extension services and farmer training.

Conclusion:

India’s paddy-centric growth has strengthened food security and farmer incomes, but its long-term sustainability depends on crop diversification toward pulses, oilseeds and millets, ensuring water conservation, fiscal balance and nutritional security while maintaining stable livelihoods for farmers.

Source: Indian Express

|

Practice Question

Q. “India’s emergence as the world’s largest rice producer has ensured food security but also created serious challenges related to water stress, fiscal burden and crop diversification.” Critically examine. (250 words)

|

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

India has become the largest rice producer due to expanded area under paddy, improved yields, assured MSP-based procurement, and strong export demand.

Farmers prefer paddy because of assured procurement, higher and stable returns, extensive infrastructure, and lower market risk compared to pulses and oilseeds.

Paddy is highly water-intensive, contributes to groundwater depletion, methane emissions, and discourages crop diversification.