Judges are removed through a strict parliamentary and quasi-judicial process under Article 124(4) and the Judges Inquiry Act. No judge has been removed so far. The system balances accountability and independence but faces challenges from high thresholds, political motives and calls for reform.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: TIMESOFINDIA

Over 100 opposition Lok Sabha MPs submitted a removal motion against Madras high court Justice GR Swaminathan to Lok Sabha Speaker Om Birla.

The process for removing Supreme Court and High Court judges balances judicial independence with public accountability.

The Constitution does not use the word ‘impeachment,’ but the term refers to the removal proceedings for Supreme Court (Article 124) and High Court (Article 218) judges.

Constitutional and Legal Framework

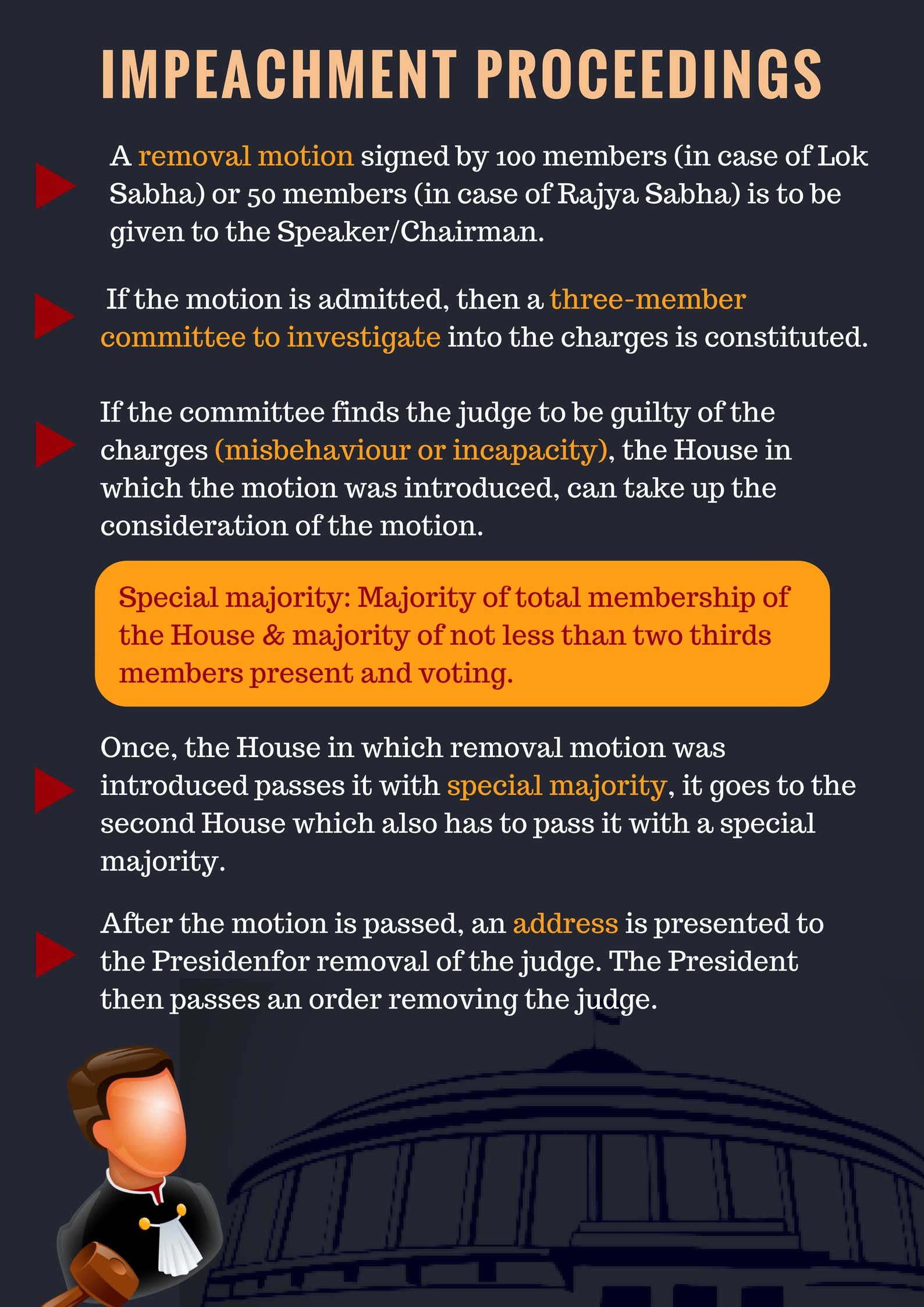

Step 1: Initiation of the Motion

Step 2: Constitution of an Inquiry Committee

Parliamentary Vote and Removal

What is 'In-House' Disciplinary Mechanism?

What is 'In-House' Disciplinary Mechanism?

Six impeachment attempts have been made against judges since Independence, but none have succeeded yet.

Key Challenges in Ensuring Judicial Accountability

High Bar for Removal: The special majority required in Parliament makes the process extremely difficult, reserving it only for the most severe cases of misconduct.

Procedural Gaps: A judge can halt the entire process by resigning, thereby avoiding a formal finding of guilt and retaining post-retirement benefits.

Lack of Transparency: The in-house inquiry is conducted confidentially, which leads to public criticism and calls for greater transparency to maintain trust in the judiciary.

Potential for Political Misuse: There are concerns that the threat of impeachment can be used as a political tool to pressure the judiciary, undermining independence.

Strengthening the accountability framework requires careful reforms that do not compromise judicial independence, which is a part of the 'basic structure' of the Constitution.

Reforming Judicial Appointments: A transparent, objective system is essential for judicial appointments. The 2015 Supreme Court ruling striking down the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) highlights the need for a balanced appointment mechanism.

Increasing Transparency: Publishing in-house inquiry findings, particularly in proven serious misconduct cases, could boost public trust and accountability.

Codifying Judicial Standards: Strengthening compliance to ethical codes like the 'Restatement of Values of Judicial Life' is essential to prevent misconduct at its root.

Constructive Dialogue: A balanced legislature-judiciary discourse is vital. Parliament's constitutional check on the judiciary requires restraint to maintain the separation of powers.

To balance judicial independence and accountability effectively, India's rigorous judicial removal process necessitates continuous, transparent reforms to address procedural gaps and strengthen public trust.

Source: TIMESOFINDIA

|

PRACTICE QUESTION Q. The 'In-House Inquiry Procedure' for judges was established by the Supreme Court in which case? (a) Kesavananda Bharati vs State of Kerala (b) S.P. Gupta vs Union of India (c) C. Ravichandran Iyer vs Justice A.M. Bhattacharjee (d) Indira Gandhi vs Raj Narain Answer: C Explanation: The Supreme Court adopted the in-house procedure in 1999, prompted by its observations in the C. Ravichandran Iyer vs Justice A.M. Bhattacharjee (1995) case, which highlighted the need for an internal mechanism to address complaints against judges. |

A judge can be removed only on the grounds of "proved misbehaviour" or "incapacity" as laid down in Article 124(4) of the Constitution. These terms are not defined in the Constitution but are interpreted through judicial precedent and legal statutes.

The process can be initiated in either House of Parliament. It requires a removal motion to be signed by at least 100 members of the Lok Sabha or 50 members of the Rajya Sabha.

Impeachment is a formal constitutional and parliamentary process for the removal of a judge. The in-house inquiry is an internal, non-statutory mechanism established by the Supreme Court to deal with complaints of misconduct that may not warrant full impeachment, focusing on internal discipline.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved