An unprecedented deep-water marine heatwave has killed nearly 70% of corals in surveyed sections of Ningaloo Reef. Framework-building species have collapsed, resilient zones have also bleached, and prior stressors like 2022 hypoxia worsened vulnerability. Global ocean warming and record heatwaves have turned this into a systemic ecological crisis affecting biodiversity, reef stability, and regional ecosystems.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: Down to Earth

Ningaloo Reef, a UNESCO World Heritage site in Western Australia, has experienced the longest, largest and most intense marine heatwave ever recorded in Australia, causing nearly 70% coral mortality in the surveyed northern lagoon areas.

|

Must Read: Coral reefs | Coral bleaching at Great Barrier Reef | CORAL BLEACHING | CORAL TRIANGLE | |

Corals are marine invertebrates made up of many genetically identical tiny organisms called polyps. These polyps live together in large colonies and secrete calcium carbonate, which forms the hard structure of coral reefs.

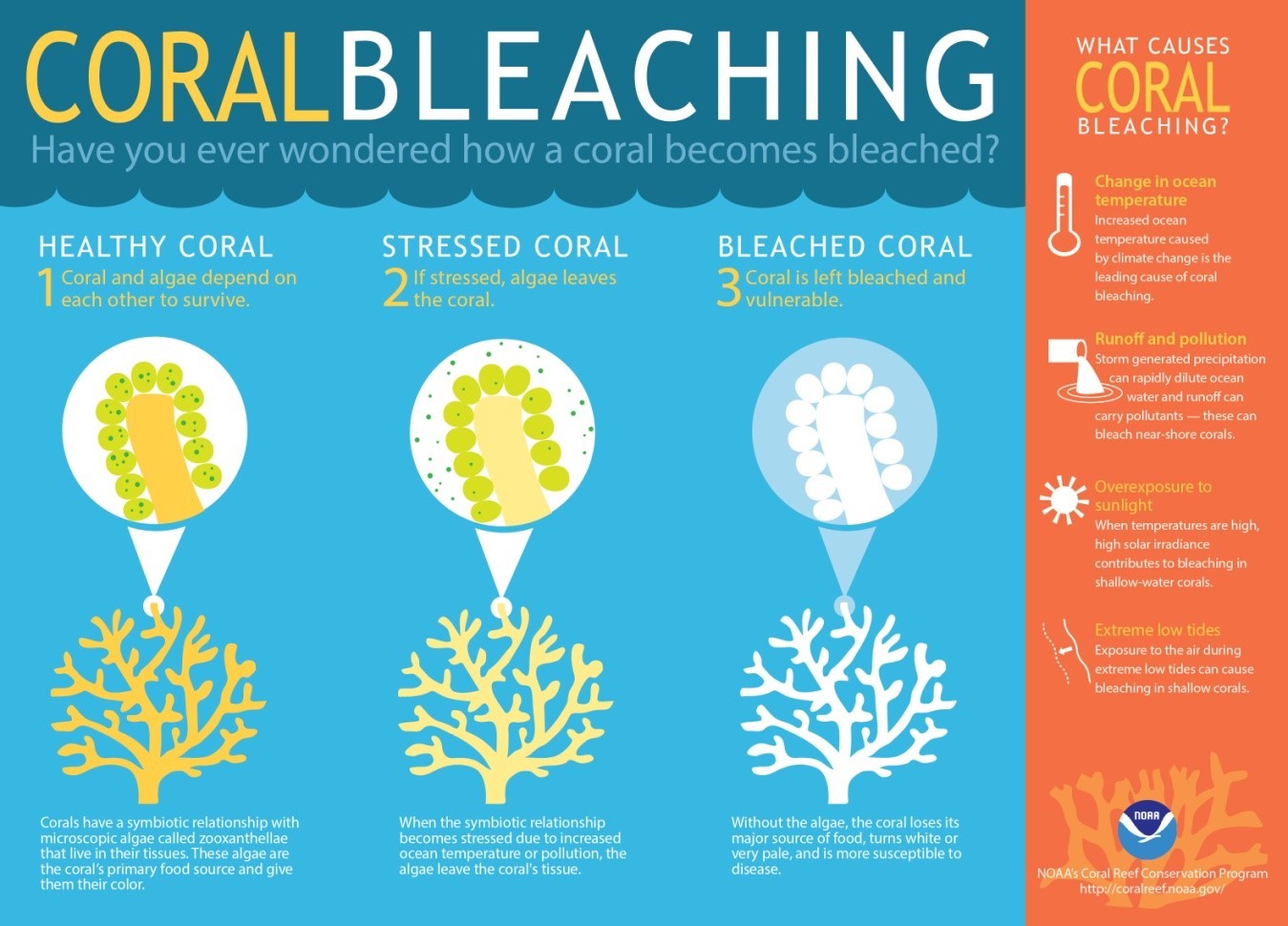

A key feature of corals is their close association with zooxanthellae, which are microscopic algae that live inside their tissues.

Symbiotic Relationship with Zooxanthellae

Corals and zooxanthellae share a mutualistic relationship:

These nutrients help corals grow and build their calcium carbonate skeletons. The presence of zooxanthellae also gives corals their bright and vibrant colors.

Support biodiversity: Coral reefs are one of the most diverse ecosystems on Earth. They provide habitat, breeding grounds, and feeding areas for a wide variety of marine species, including fishes, crustaceans, molluscs, and many other organisms.

Coastal protection: Reefs act as natural barriers, absorbing wave energy and reducing the impact of storms, erosion, and coastal flooding. This protects shorelines, beaches, and coastal settlements.

Fisheries and livelihoods: Coral reefs support significant fisheries, especially in tropical countries. Millions of people depend on reef-associated fish for food and income.

Tourism and economy: Reefs attract tourists for activities such as scuba diving and snorkeling. This creates major economic benefits for coastal communities through tourism-related services.

Carbonate balance and marine productivity: Corals build large calcium carbonate structures that influence nutrient cycles, water clarity, and overall productivity of tropical marine ecosystems.

Hard Corals (Scleractinian Corals): These are reef-building corals.

Examples: Acropora, Porites, Montipora.

Soft Corals (Alcyonacean Corals): These do not build reefs because they lack hard skeletons.

Examples: Sea fans, sea whips, sea pens.

What is Coral Bleaching?

Coral bleaching is a process in which corals lose their colour because they expel or lose their symbiotic algae called zooxanthellae. These algae normally live inside coral tissues and provide the corals with food through photosynthesis and also give them their bright colours.

When corals are stressed—mainly due to high sea temperatures, but also due to pollution, sedimentation, or changes in salinity—they push out the zooxanthellae. Without these algae corals turn white or pale, their energy supply drops sharply, and they become weak and more vulnerable to disease and death.

Picture Courtesy: NOAA

Unprecedented Marine Heatwave: Ningaloo experienced the longest, largest, and most intense marine heatwave ever recorded in Australia. This prolonged heating pushed corals beyond their thermal tolerance, leading to widespread bleaching and mortality.

Deep-Water Heating: The entire water column, down to 300 metres, became superheated. This eliminated cooler refuges that corals normally rely on during warm periods, increasing mortality.

Prolonged Temperature Stress (Late 2024–Mid 2025): Heat accumulated for months, leaving no recovery window for bleached corals. Most corals that bleached in March did not survive by October.

High Bleaching Intensity Across Reef Types: Bleaching affected not only shallow areas but also offshore and previously resilient sites, including Rowley Shoals and northern Kimberley.

Collapse of Dominant Structural Coral Species: Species highly sensitive to heat—such as staghorn corals (Acropora spp.) and thin birdsnest coral (Seriatopora hystrix)—experienced high mortality. Loss of these key structure-building species increased overall reef vulnerability.

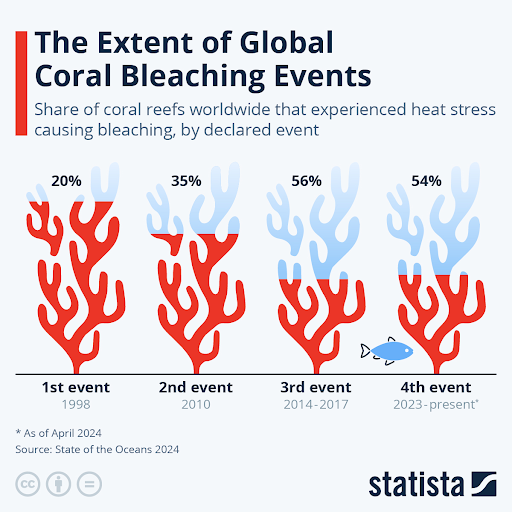

Picture Courtesy: Statista

Heatwaves of unprecedented depth and duration: Heating extended to 300 metres, eliminating cool-water refuges that might otherwise buffer corals. Traditional resilience mechanisms (e.g., internal waves, upwelling) were ineffective.

Compounded stress from earlier events: The reef arrived at 2024–25 already weakened by prior, severe local disturbances. A clear case is Bills Bay (Coral Bay) where a deoxygenation event in 2022 following coral spawning knocked live coral cover from 70% (2021) to 1% (2022), and turf algae rapidly took over. Such prior collapse removes ecological redundancy (fewer species and colonies to supply larvae or structural framework), so when a regional heatwave arrives the reef’s capacity to resist and recover is much lower.

Limited recovery window: Ningaloo’s bleaching and mortality occurred with short intervals between thermal peaks. Successful reef recovery requires time for coral colonies to regrow and for larval recruitment to replenish populations.

Loss of structurally important species: Mortality has been highest among framework-forming corals (e.g., Acropora spp., Seriatopora), which build complexity that supports reef biodiversity. When framework corals collapse, the reef’s physical architecture erodes

|

Category |

Indian Government Initiatives |

Global Initiatives |

|

Monitoring and Early Warning |

• Zoological Survey of India conducts long-term coral monitoring in the Gulf of Mannar, Gulf of Kachchh, Lakshadweep Islands, and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. • Reef surveillance under the Integrated Coastal Zone Management Project by coastal States and Union Territories. |

• National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Coral Reef Watch provides global heat-stress alerts. • Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network publishes global bleaching assessments. |

|

Policy and Governance |

• National Coastal Mission under the National Action Plan on Climate Change includes coral-reef vulnerability assessments. • Coastal Regulation Zone Notification of 2011 restricts damaging coastal activities, dredging, and unregulated tourism. |

• The Paris Climate Agreement aims to limit global warming, which is essential for coral survival. • International Coral Reef Initiative coordinates international policy and bleaching-response guidelines. |

|

Protection Measures |

• Marine National Parks and Marine Sanctuaries such as the Gulf of Mannar Marine National Park protect coral ecosystems. • Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 prohibits coral mining and destructive fishing practices. |

• Great Barrier Reef Marine Park in Australia and the Chagos Marine Protected Area in the Indian Ocean are large protected coral systems. • Global “Thirty by Thirty” oceans protection target promotes protection of thirty percent of the world’s oceans by the year 2030. |

|

Restoration and Regeneration |

• Coral transplantation and reef restoration by the Suganthi Devadason Marine Research Institute in the Gulf of Mannar. • Coral gardening and micro-fragmentation programs in Lakshadweep and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands by national research institutes. |

• Australia’s Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program works on heat-tolerant corals and larval restoration. • Seychelles’ Reef Rescuers Programme uses large-scale coral gardening. • Coral nurseries in the Florida Reef Tract assist in reef rebuilding. |

|

Reducing Local Stress |

• Controls on coastal pollution, dredging, plastic litter, and unregulated tourism near sensitive reef areas. • Blue Flag Beach Programme promotes clean water quality and sustainable coastal management. |

• Sunscreen bans in Palau, Hawai‘i, and Thailand to prevent harmful chemicals from damaging corals. • Community-managed fisheries restrictions in Fiji, Samoa, and other Pacific island nations reduce pressure on coral ecosystems. |

|

Community and Indigenous Participation |

• Engagement of local fishing communities in Tamil Nadu and Gujarat for reef stewardship. • Community participation and traditional knowledge in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands for sustainable reef protection. |

• Indigenous Sea Country Ranger Groups in Australia manage reef areas using traditional ecological knowledge. • Locally Managed Marine Areas in Pacific Island Nations support community-based coral protection. |

|

Climate Action and Funding |

• India’s national commitments under global climate agreements indirectly support coral resilience by reducing warming. • Coastal protection and ecosystem-based adaptation projects funded through national climate programs. |

• Global Environment Facility, Green Climate Fund, and Global Fund for Coral Reefs finance coral conservation worldwide. • “Blue Bonds,” such as the one issued by Belize, support marine conservation and reef protection. |

|

Research and Innovation |

• National Centre for Sustainable Coastal Management, National Institute of Ocean Technology, Suganthi Devadason Marine Research Institute and Botanical Survey of India conduct research on coral ecology and restoration. |

• Marine cloud brightening trials, artificial shading structures, and larval enhancement experiments in Australia and the Maldives. • Deep-water thermal refuge mapping by research institutions in Japan and Australia. |

Temperature stress forecasting and deep-water monitoring: Expand high-resolution monitoring to include entire water column to detect deep-water heat anomalies. Deploy autonomous underwater vehicles for long-term heat stress mapping.

Identify and protect surviving resilient species: Species like Echinopora ashmorensis and Cyphastrea microphthalma show tolerance. Prioritize these for selective propagation, assisted evolution, and nursery programs.

Expand thermal refugia and shading interventions: Explore small-scale cooling interventions near high-value tourism sites (e.g., cloud brightening trials, shading systems) and identify naturally cooler refuges for targeted conservation.

Strict control on local stressors: Minimizing nutrient pollution and tourism pressure near vulnerable zones (Turquoise Bay, Osprey Sanctuary, Tantabiddi Sanctuary) to enhance surveillance for algal overgrowth and sponge proliferation.

Integrate marine heatwaves into climate risk planning: Marine heatwaves must be treated as major climate disasters requiring formal risk frameworks similar to bushfires and droughts.

Ningaloo Reef is undergoing one of the most severe coral mortality events ever recorded in Australia, driven by an unprecedented deep-water marine heatwave and compounded by earlier ecological stress. The scale and rapidity of decline signal a systemic climate-driven crisis requiring immediate regional conservation measures and global action on ocean warming.

Source: Down to Earth

|

Practice Question Q. Coral bleaching in recent years has become more frequent, widespread, and severe. Discuss the major causes of coral bleaching and critically evaluate the effectiveness of Indian and global initiatives aimed at mitigating its impacts. (250 words) |

Because heating extended through the entire water column (~300 m), eliminating thermal refuges and subjecting corals to sustained, multi-month stress.

Heat stress thresholds were exceeded region-wide, overwhelming even historically stable reef systems.

Framework-forming Acropora species and Seriatopora hystrix, which are essential for reef structure and habitat diversity.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved