The recent ruling by the Supreme Court of India recognises access to menstrual hygiene as part of fundamental rights, linking it to equality, dignity, privacy, and the right to education. The Court held that lack of sanitary products and proper school facilities forces many girls to miss classes, which amounts to structural discrimination under Article 14 and a violation of dignity under Article 21. It directed governments to provide free sanitary napkins, functional and private toilets, safe disposal systems, menstrual hygiene support spaces, and awareness through school curricula, making menstrual health a legal and educational priority rather than a welfare issue.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: Indian Express

Context:

Supreme court in the case Dr. Jaya Thakur vs. GOI & ORS has officially recognized Menstrual Health and hygiene as a Fundamental right under Article 21.

|

Must Read: MENSTRUAL HYGIENE | MENSTRUAL HYGIENE IN INDIAN PRISONS | TABOO AROUND MENSTRUATION | |

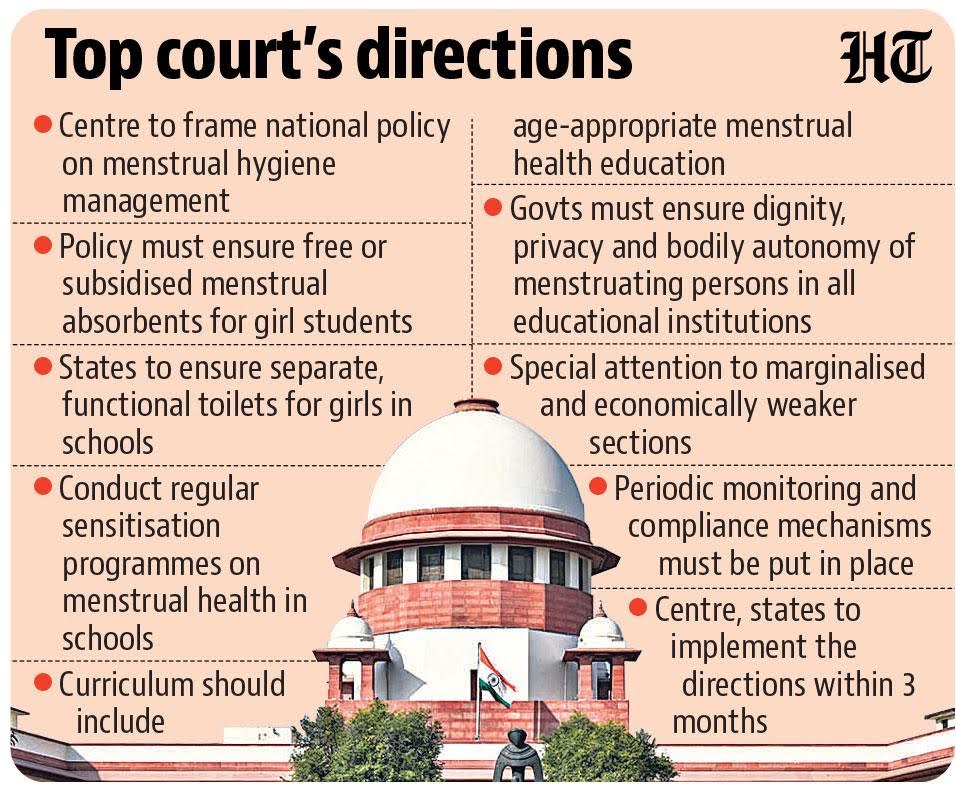

Supreme court rulings on Menstrual Hygiene and Health:

Constitutional foundation: The Supreme Court of India ruled that access to menstrual hygiene is a matter of constitutional protection, explaining that equality under Article 14 must be understood in a substantive sense, which means the State must address biological and social disadvantages faced by girls rather than treating everyone identically. The Court further held that menstrual health falls within the right to live with dignity under Article 21, observing that stigma, shame, and school absenteeism linked to menstruation undermine bodily autonomy, privacy, and self-worth.

Right to Education interpreted in a practical sense: Reading the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act purposively, the Court clarified that “free education” cannot be limited to waiver of tuition fees, because when girls are forced to miss classes due to the cost or unavailability of menstrual products, education effectively becomes conditional, which defeats the object of the law.

Mandatory facilities schools must provide: The judgment directs that all schools, whether government or private, must supply free sanitary napkins to girl students in an environmentally sustainable manner, install safe and hygienic disposal systems, and maintain functional, private, gender-segregated toilets with running water, soap, and facilities accessible to children with disabilities. Schools must also create Menstrual Hygiene Management corners stocked with emergency supplies such as spare uniforms and disposal bags so that menstruation does not force a child to leave school mid-day.

Education and sensitisation measures: The Court emphasised that infrastructure alone is not enough and therefore instructed the National Council of Educational Research and Training and state bodies to integrate age-appropriate, gender-sensitive education on puberty and menstruation into school curricula, while requiring that all teachers receive training to support students and help dismantle stigma, including sensitising boys to foster a respectful school environment.

Monitoring and accountability: To ensure these directions are actually implemented, the Court ordered periodic inspections by District Education Officers and required that anonymous student feedback be collected so that the lived reality of girls in schools informs ongoing compliance.

Picture Courtesy: Hindustan Times

Importance of Supreme court ruling on Menstrual Hygiene and Health:

Menstruation affecting school attendance: According to National Family Health Survey across India have shown that a significant proportion of adolescent girls miss school during their periods due to lack of sanitary products, privacy, or proper toilets, with some studies estimating that 1 in 5 girls has skipped school at least once because of menstruation-related challenges. This absenteeism often compounds over time, increasing the risk of dropouts at the secondary level.

Sanitation gaps in schools were a structural barrier: Government and independent assessments of school infrastructure have repeatedly found that while many schools report having girls’ toilets on paper, a large number are non-functional, lack water supply, or offer no privacy, making them unusable during menstruation. The Court’s directions address this gap between infrastructure claims and ground reality.

Cost of sanitary products was a hidden education expense: For families in low-income households, monthly spending on sanitary napkins can be a burden, especially where there are multiple adolescent girls. Affordability issues push many girls toward unsafe alternatives, which not only affect health but also increase discomfort and school absence. By making napkins free in schools, the verdict removes a recurring financial barrier linked directly to attendance.

Link between menstrual hygiene and dropout rates: Education research in India has long noted a visible dip in girls’ retention rates around puberty, particularly in rural and economically weaker communities. Lack of menstrual support, coupled with stigma and poor facilities, has been identified as one of the contributing social factors. The ruling therefore targets a key but often overlooked reason behind gender gaps in secondary education

Key concerns in implementing Menstrual Health & Hygiene (MHH) guidelines:

Government initiatives:

Key measures to strengthen Menstrual Health & Hygiene (MHH):

Conclusion:

The recent Supreme Court verdict recognising access to menstrual hygiene as a constitutional right is a landmark step toward gender justice, equality, and dignity; it not only mandates structural changes in schools but also transforms long-standing social barriers into enforceable state duties, ensuring that menstruation no longer hinders a girl’s right to education and full participation in society.

Source: Indian Express

|

Practice Question Q. “Menstrual hygiene is no longer merely a public health concern but a matter of constitutional rights.” Discuss in the context of the recent judgment of the Supreme Court of India. (250 words) |

The Supreme Court of India declared that access to menstrual hygiene is part of fundamental rights, linking it to equality, dignity, privacy, and the right to education, and directed governments to ensure facilities and free sanitary products in schools.

The Court held that when girls miss school due to lack of sanitary products or safe toilets, it amounts to discrimination and loss of dignity, bringing the issue within Article 14 and Article 21.

Schools must provide free sanitary napkins, safe disposal systems, functional and private girls’ toilets with water and soap, and emergency menstrual hygiene supplies such as spare uniforms.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved