The 130th Constitutional Amendment Bill, 2025, seeks to criminalize politics by amending Articles 75, 164, and 239AA, requiring the removal of Prime Ministers, Chief Ministers, or ministers for 30 consecutive days for serious charges. The government supports this move for political morality and governance, but opposition concerns arise about potential misuse and violating the principle of innocence.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: THE HINDU

The proposed Constitution (130th Amendment) Bill aims to address political corruption by removing jailed ministers, however concern raised over its broad scope.

Constitutional gap: Under current law, no provision automatically removes a minister upon arrest. Articles 75 (Union Ministers), 164 (State Ministers) and 239AA (Delhi) govern appointment and tenure. They require ministers (including PM/CM) to be MPs/MLAs within six months, and say they hold office “during the pleasure” of the President/Governor.

Kejriwal & other cases: The issue surfaced when Delhi CM Arvind Kejriwal spent 5+ months in ED custody (liquor policy case) in 2024. The Supreme Court granted him bail but barred him from official duties; he later resigned.

Criminalisation of politics: Corruption and crime among politicians have long been concerns.

| ELECTORAL REFORM IN INDIA: CHALLENGES AND WAY FORWARD |

| CRIMINALIZATION OF POLITICS |

Proposed Amendment: The Bill inserts new clauses into three Articles.

Mechanism: Any PM, CM, or Union/State minister arrested for a “serious” crime (defined as offences punishable by ≥5 years’ jail) and held in custody for 30 consecutive days will lose office.

Removal procedures: For Union ministers (including PM), the President removes the minister on the PM’s advice by day 31 of custody. For a detained Prime Minister, he must resign by the 31st day or else his office automatically falls vacant.

Re-appointment: The Bill allows a removed minister to return after release. If bail is secured within 30 days, no action is taken. If removal happens, the person may be re-appointed once out of custody.

Government Justifications: The Statement of Objects and Reasons of the Bill emphasizes “constitutional morality and good governance.”

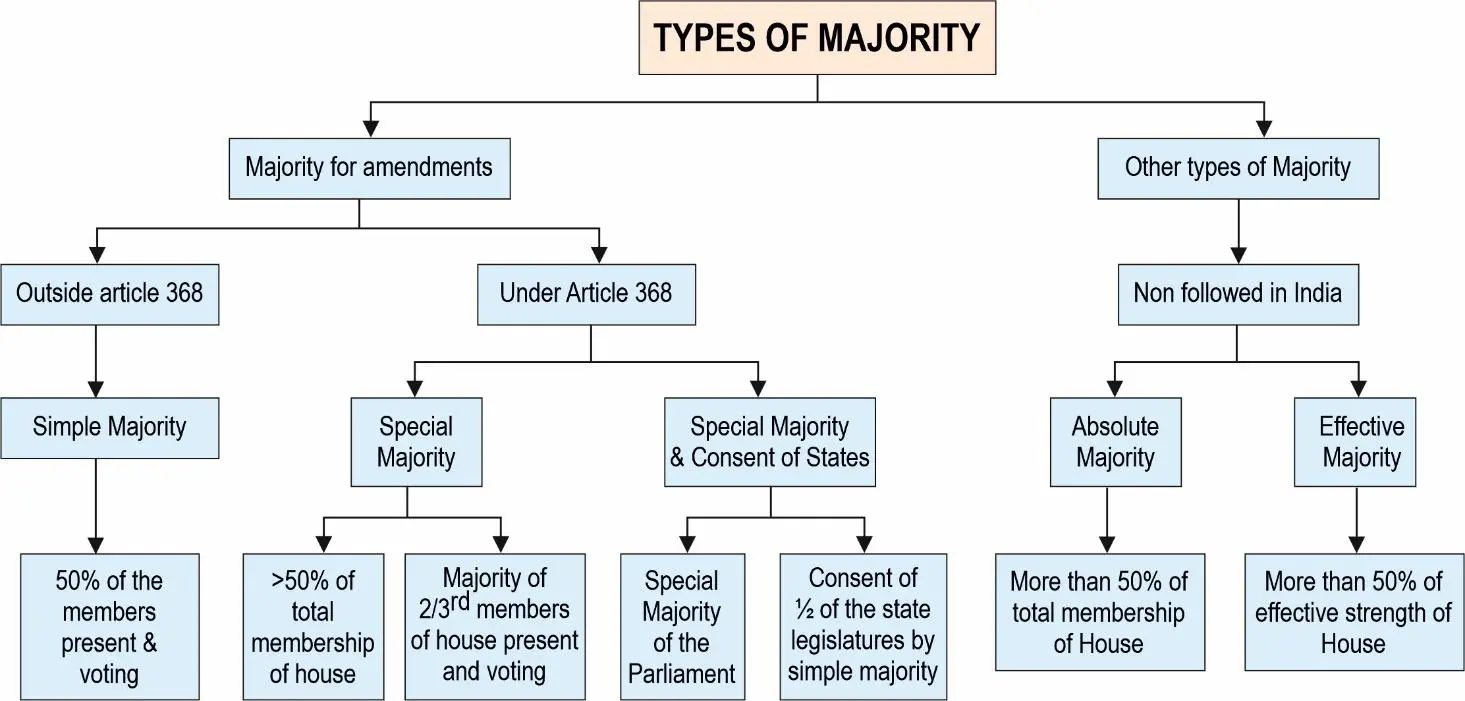

Parliamentary procedure: Constitutional amendment requires a special majority (two-thirds of members present and voting). Both Houses send the Bill to a Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) for detailed scrutiny. The JPC (with members from all parties) will examine it.

Complementary legislation: To extend the reform uniformly, the government introduced two sister bills.

Complementary legislation: To extend the reform uniformly, the government introduced two sister bills.

Against Parliamentary procedure: Critics note the act of introducing it last-minute – bypassing normal notice rules – was seen as undemocratic.

Constitutional & legal issues: Critics argue it undermines the presumption of innocence by removing someone before any conviction.

Conflict with the Doctrine of Pleasure: The bill modifies the "doctrine of pleasure," by creating a provision for automatic removal, it introduces a statutory limitation on this doctrine, shifting power from a political decision to a condition based on the actions of law enforcement agencies.

Practical implementation issues: Ambiguities remain. What exactly qualifies as a “serious offence” (≥5-year punishment)? Some financial crimes or POCSO offences carry 5-year terms but vary widely in gravity.

Democratic process concerns: Concern raised that by forcing resignations mid-term, the voters’ choice (especially when a CM is removed) is indirectly toppled.

|

Supreme Court Precedents Public Interest Foundation (2018): A five-judge SC bench unanimously held that it had no power to disqualify candidates merely on charges; doing so would usurp Parliament’s role.

Manoj Narula vs Union (2014): In this case, a 5-judge bench considered whether persons with criminal charges can be appointed ministers.

|

Tightening definitions: Bill defines “serious offences (≥5 years)” and detention (30 days) to limit scope. Lawmakers must ensure clarity to prevent loopholes or overreach.

Judicial safeguards: The amendment could be refined to trigger removal not upon arrest, but only after a court has framed charges against the minister. This would introduce a layer of judicial scrutiny, aligning with the recommendations of the 170th and 244th Law Commission Reports."

Strengthening the Role of the Governor/President: Current proposal makes the removal automatic or based on prime ministerial/chief ministerial advice.

Electoral Reforms as the Root Solution: While this bill is a potential cure, preventing the entry of candidates with criminal backgrounds through electoral reforms is the more sustainable, long-term solution.

Political accountability: Parties should screen candidates more strictly; disfavor those under serious investigation.

Bipartisan dialogue: Given federal concerns, the Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) studying the bill should consider states’ views. Constructive debate may yield provisions to limit political use.

Sunset or review clauses: The new rules could be revisited after a trial period to assess impact. For example, if courts find many wrongful disqualifications, Parliament could refine the law.

Police and Investigative Reforms: The core issue is the lengthy pre-trial detention, which need a broader criminal justice reforms, such as those recommended by the Malimath Committee, to ensure speedier trials. If trials are completed in a time-bound manner, the need for such a bill would be diminished.

The amendment bill aim – cleaner, more ethical leadership – has wide appeal, but its design must guard against collateral damage to the rule of law and federal balance. Close parliamentary scrutiny, possible judicial review, and complementary reforms in the criminal justice system (e.g. faster trials, stronger anti-corruption enforcement) will be key to making this amendment effective and fair.

Source: THE HINDU

|

PRACTICE QUESTION Q. Analyze the provisions of the 130th Constitutional Amendment Bill, 2025. Do you think it is a necessary step to curb the criminalization of politics? 250 words |

It is a proposed law to remove a Prime Minister, Chief Minister, or minister if they are arrested for a serious crime and held in custody for 30 consecutive days.

A JPC is a special body with members from both houses of Parliament that is formed to scrutinize a bill in detail, allowing for a comprehensive, cross-party review.

To provide a legal framework for the removal of ministers who are arrested and detained for a continuous period of 30 days on serious criminal charges.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved