A meat tax is being proposed globally as a climate policy tool to reduce the environmental impact of livestock, a sector responsible for 12–19% of global greenhouse gas emissions, especially methane. The tax aims to curb overconsumption—particularly in high-income countries—internalise ecological costs like deforestation and land degradation, and generate revenue for climate action such as the Loss and Damage Fund. However, its implementation faces challenges including political resistance, livelihood concerns for farmers, cultural sensitivities, equity issues for low-income consumers, and difficulties in measuring emissions accurately. While the tax offers a pathway toward sustainable and climate-resilient food systems, it requires careful design to ensure fairness and effectiveness.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: Down to Earth

At COP30 (Belém, Brazil), 28 low-income African and Pacific nations demanded a GHG emission pricing mechanism (‘meat tax’) on industrial meat production in high-income economies.

Their argument builds on the polluter-pays principle and climate justice: nations that consume more meat and run carbon-intensive livestock systems must compensate those disproportionately suffering from climate impacts, especially sea-level rise and extreme events.

Picture Courtesy: Research gate

A meat tax is a government-imposed charge or levy on the production, sale, or consumption of meat, especially high-emission animal products like beef, pork, and lamb.

It is designed to reflect the true environmental and health costs of meat production, which are currently not included in market prices

Why it is proposed?

Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions: A meat tax is proposed primarily to reduce the climate impact of livestock systems, which contribute 12–19% of global GHG emissions, particularly through methane from cattle.

Discouraging Overconsumption: High-income countries consume four to five times more meat per person than sustainable dietary limits, placing immense pressure on land, water, and energy resources. A meat tax is intended to moderate this overconsumption by making high-emission meat products relatively more expensive.

Funding climate action and supporting just transitions: A meat tax would also generate substantial revenue that can be channelled into climate-related needs. The environmental footprint of livestock disproportionately affects vulnerable populations and climate-sensitive regions.

Political Resistance: A meat tax directly affects consumer prices, making it politically sensitive. In many countries, meat is culturally important and seen as a basic dietary item, leading to public resistance against what may be perceived as “food taxation.” A government-appointed ethics council in Denmark recommended a $2.30 per kg tax on beef, but it was dropped after public backlash and opposition from farmer groups.

Impact on farmers and rural livelihoods: Livestock rearing supports millions of smallholders, pastoralists, and rural families. A poorly designed tax could reduce farm incomes, threaten livelihoods, and widen rural distress. For example: Over 20.5 crore livestock-dependent people rely on mixed farming for income; any tax could disproportionately impact marginal farmers unless carefully designed.

Equity concerns for low-income consumers: Although high-income consumers eat the most meat, a uniform tax affects all consumers equally. Low-income households may bear a disproportionate burden, especially in countries where meat is an important source of affordable protein. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries consume 71 kg meat/year, developing countries average 26 kg, indicating uneven impacts across income groups.

Risk of informal markets and smuggling: Steep taxes may incentivise black markets, illegal slaughter, and unregulated trade, especially in countries with weak enforcement. This undermines the environmental purpose of the tax and creates additional public health and sanitation risks. Cattle slaughter restrictions in certain states have historically increased illegal transport and unregulated slaughter, risking hygiene and safety standards.

Trade implications and WTO compliance: A meat tax could distort trade competitiveness, raising disputes under WTO rules if exporters perceive the policy as disguised protectionism. Brazil world’s largest beef exporter fears carbon-based meat taxes in the EU could function as non-tariff barriers.

|

Measure |

Description |

Impact |

|

Innovative Feed Supplements |

Harit Dhara reduces methane emissions in bovines and sheep |

17–20% methane reduction; improves milk & weight gain |

|

National Livestock Mission |

Breed improvement, balanced rationing, green fodder production |

Enhances productivity, lowers emissions |

|

Gobardhan Scheme |

Cattle waste used for clean energy & organic manure |

Reduces methane from manure |

Adopt a differential, equity-sensitive tax design: A uniform meat tax may hurt low-income consumers and small farmers. A graded tax—higher on high-emission meats like beef and lower on poultry—ensures fairness.

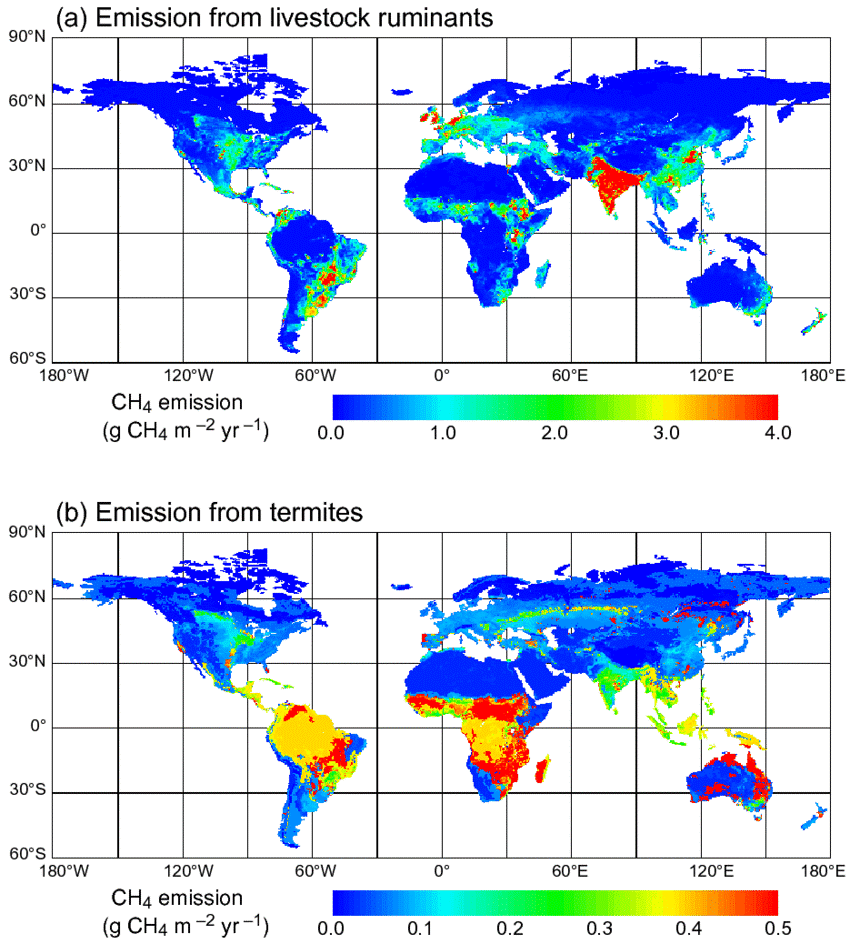

Improve Emission Measurement: A credible meat tax requires accurate measurement of livestock emissions across production systems. Strengthening monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) frameworks—drawing on technology like sensors, remote sensing, and lifecycle assessments—is crucial for transparency and trust.

Strengthen Waste-to-Wealth: Investing in biogas, bio-CNG, composting, and slurry management can reduce methane emissions while offering farmers economic returns.

Promote Dietary Awareness: Public campaigns, school curricula, and labelling systems can encourage healthier and climate-friendly diets. Instead of coercion, nudges that highlight the environmental footprint of foods help shift consumption patterns without cultural backlash.

A meat tax represents an attempt to align food systems with climate and environmental realities by internalising the hidden costs of livestock emissions, land degradation, and overconsumption. While it can drive significant behavioural change and generate vital climate finance, its effectiveness depends on equitable design, strong monitoring, and safeguards for farmers and low-income consumers. Ultimately, a meat tax is not just a fiscal tool but a pathway toward more sustainable, fair and resilient global food systems.

Source: Down to earth

|

Practice Question Q. A meat tax has been proposed globally as a tool to reduce livestock emissions and promote sustainable food systems. Discuss (250 words) |

A meat tax is a levy imposed on the production or consumption of meat—especially high-emission products like beef or pork—to account for environmental costs such as methane emissions, deforestation, and land degradation.

Because livestock contributes 12–19% of global GHG emissions, and high-income countries consume 4–5 times more meat than sustainable limits. A tax incentivises lower emissions and generates revenue for climate action.

High-income consumers and industrial livestock producers. Poor consumers may feel the impact if the tax is not designed with safeguards like subsidies or differential rates.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved