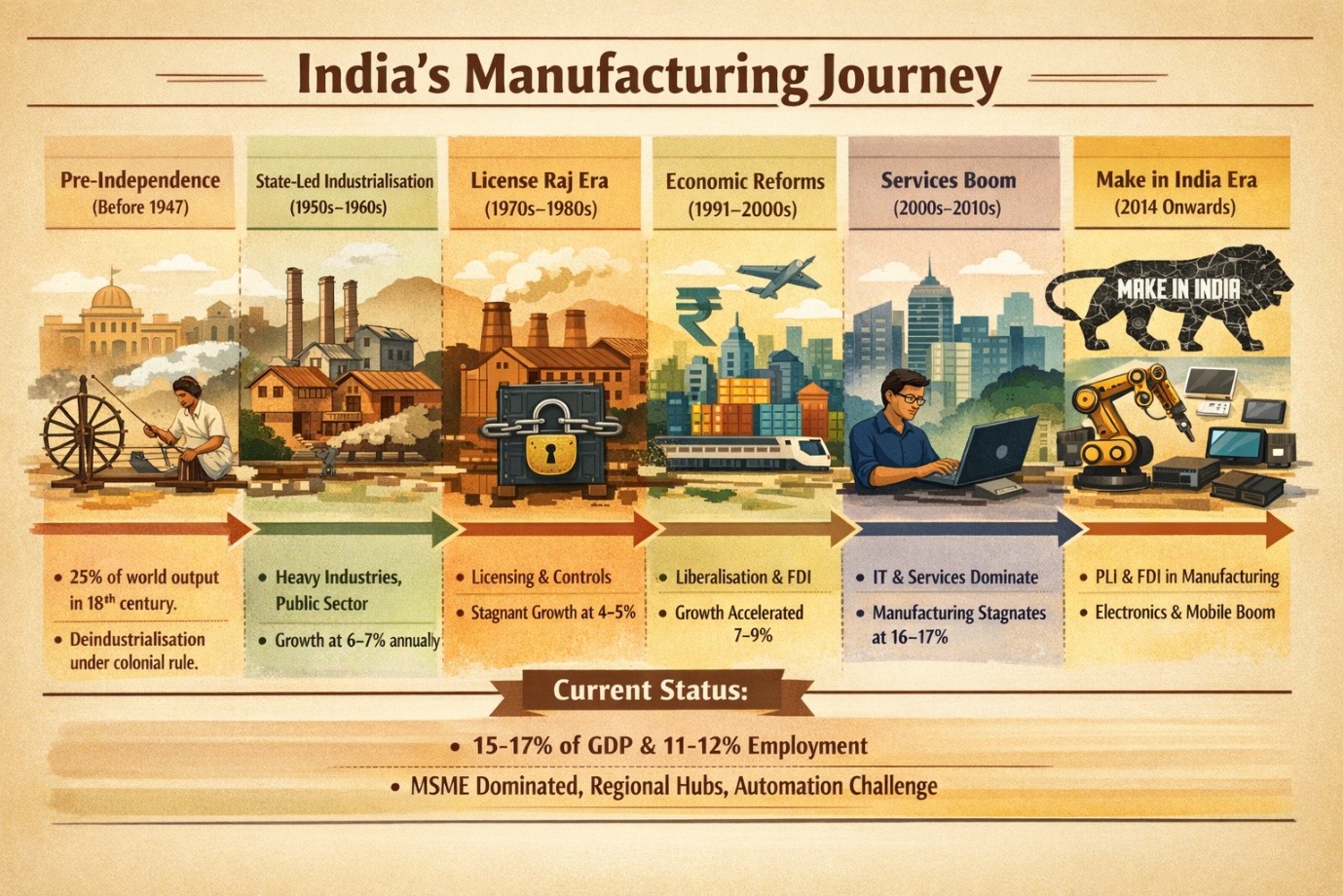

The manufacturing sector plays a crucial role in India’s economic development by generating large-scale employment, boosting GDP growth, and driving structural transformation from agriculture to industry. However, its performance has remained below potential, with the sector contributing only about 15–17% of GDP and around 11–12% of total employment. Constraints such as high logistics costs, infrastructure gaps, low R&D spending, skill mismatches, regulatory complexity, and dominance of informal enterprises have slowed progress. Government initiatives including Make in India, Production Linked Incentive schemes, PM Gati Shakti, Atmanirbhar Bharat, and Skill India aim to raise competitiveness, enhance domestic value addition, and integrate India more deeply into global value chains. Overall, manufacturing remains central to India’s growth strategy, but sustained reforms and investment are needed to fully realise its potential.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: The Hindu

India’s manufacturing share in GDP has remained largely stagnant and has recently been overtaken by services, while China and South Korea experienced large increases in manufacturing output and employment.

|

Must Read: India’s Manufacturing Sector and PMI | REVAMPING SEZS | SUNRISE SECTORS | |

|

Phase |

Description |

|

Pre-Independence (before 1947) |

India had a strong artisanal and handicraft manufacturing base in textiles and metal goods, but colonial policies led to deindustrialisation; India’s share in world manufacturing output declined from 25% in early 18th century to <2% by 1947, while traditional textile industries collapsed and the country was converted into a raw material supplier. |

|

Early Post-Independence: State-led Industrialisation (1950s–1960s) |

The Nehru–Mahalanobis strategy promoted heavy industries under the public sector, with steel, machinery and engineering capacity created; manufacturing value added grew at around 6–7% annually, but the sector was protected through import substitution and licensing, which limited competitiveness and innovation. |

|

License Raj & Controlled Economy (1970s–1980s) |

Industrial licensing, small-scale reservation and trade protection restricted firm growth and technology inflow, leading to inefficiency; during this period industrial GDP growth averaged around 4–5%, and India’s share of manufacturing in GDP remained almost stagnant at 15–17%. |

|

1991 Reforms and Liberalisation Phase |

The 1991 crisis triggered deregulation, delicensing, tariff reduction and FDI liberalisation, which boosted sectors such as automobiles, cement, petrochemicals and pharmaceuticals; manufacturing growth accelerated to around 7–9% in the 2000s, yet employment generation remained weak and informalisation persisted. |

|

2000s–2010s: Services-led Growth and Manufacturing Stagnation |

Services outpaced manufacturing, with IT and finance contributing over 55% of GDP, while manufacturing’s GDP share remained around 16–17%, much lower than China’s 28–30% and South Korea’s 25–27%, reflecting India’s premature deindustrialisation and “missing middle” of medium enterprises. |

|

2014 onward: Renewed Focus on Manufacturing (Make in India, PLI) |

Policies such as Make in India, PLI schemes, labour code reforms, logistics improvement, semiconductor and electronics push increased FDI inflows into manufacturing (India received >$80 billion total FDI inflow annually in recent years, with a rising share in manufacturing), and mobile/electronics production expanded sharply, though labour-intensive manufacturing and export competitiveness are still lagging. |

|

Current Status |

Manufacturing contributes roughly 15–17% of GDP and about 11–12% of total employment, with high regional concentration in Maharashtra, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka; the sector is dominated by MSMEs, automation is rising, and India faces the challenge of creating mass industrial jobs while global manufacturing shifts toward capital-intensive technologies. |

Infrastructure and logistics bottlenecks: India’s manufacturing suffers from high logistics costs, estimated at 13–14% of GDP, compared to 8–9% in China and 7–8% in advanced economies, which reduces export competitiveness and scale efficiency. Delays at ports and congested roads increase turnaround time; for example, the average container dwell time in Indian ports has traditionally been higher than major East Asian ports. High freight costs particularly hurt sectors like textiles, leather, and engineering goods, which depend on timely delivery.

High cost of capital and limited MSME credit: The cost of capital in India is relatively high, with lending rates for MSMEs often exceeding 10–12%, discouraging long-term investment in technology and capacity expansion. According to the IFC, the MSME credit gap is estimated at over ₹20–25 lakh crore, meaning many firms operate without adequate formal finance. As a result, small manufacturers in textiles (Tiruppur), sports goods (Jalandhar) and leather (Kanpur) often rely on informal borrowing and remain stuck at low productivity.

Compliance burden: Manufacturing firms face multiple approvals relating to labour, environment, taxation, and land, increasing compliance costs. Before reforms, India had been ranked low in ease of doing business for starting a business, contract enforcement, and construction permits. Even today, state-level variations persist — Tamil Nadu and Gujarat have more efficient single-window clearances compared to lagging states. This discourages firm growth and keeps many units informal.

Labour rigidities and skill mismatch: Labour laws historically discouraged large-scale hiring, leading firms to remain small and capital-light. At the same time, there is a skill mismatch — various industry surveys report that over 40–50% of employers face difficulty finding appropriately skilled workers, despite high youth unemployment. For example, the automobile cluster in Pune and Sriperumbudur frequently reports shortages of trained shop-floor technicians, indicating weak vocational training-industry linkage.

Low R&D expenditure and technology adoption: India spends less than 1% of GDP on R&D (roughly 0.7%), whereas South Korea spends over 4% and China around 2–2.5%. This leads to limited innovation in machinery, electronics, precision engineering, and advanced materials. While India has world-class pharma capability, sectors like semiconductors, telecom equipment, and high-end electronics rely heavily on imported technology. The PLI scheme for electronics and semiconductors directly arose to address this lag.

|

Public sector wages and “Dutch disease” dynamics High government salaries in India drew workers away from manufacturing because public jobs were better paid and more secure, while factories with low productivity could not match these wages. This pushed up wages and prices across the economy, increasing production costs for manufacturers. As domestic prices rose, imports became relatively cheaper and Indian exports became less competitive. This situation is similar to “Dutch disease,” where a boom in one sector raises wages and the real exchange rate and ends up hurting manufacturing. In India, the boom did not come from oil or gas but from the expansion of high-paying government employment, which increased demand for non-tradable services and raised domestic prices. As a result, demand for domestic manufactured goods fell and industrialisation slowed down, weakening structural transformation. |

Improving infrastructure and lowering logistics costs: For India’s manufacturing sector to become efficient, goods must move quickly and cheaply from factories to markets. This requires better roads, ports, rail connectivity and warehousing so that delays and transport costs come down. Programmes such as PM Gati Shakti, National Logistics Policy 2022, Sagarmala and Bharatmala are designed to integrate transport networks, which will gradually reduce logistics costs from about 13–14% of GDP to closer to 8–9%, making Indian products more competitive.

Promoting technology adoption and research: Higher productivity in manufacturing depends on modern machines, automation and innovation. When firms invest in technology, they produce better-quality goods at lower cost and can compete globally. To support this, the government has introduced Production Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes, SAMARTH Udyog, and proposed the National Research Foundation, which encourage sectors such as electronics, pharmaceuticals, automobiles and textiles to upgrade technology and increase value addition rather than relying only on low-end assembly.

Strengthening MSMEs through finance and formalisation: Since most manufacturing units in India are MSMEs, the sector cannot become efficient unless small firms gain easier access to credit and markets. Measures like Mudra Yojana, Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme (ECLGS), CGTMSE, Udyam registration, and ZED certification help firms move from informal to formal operations, allowing them to expand, adopt new machines and meet quality standards required for exports.

Simplifying regulations and improving ease of doing business: A complex regulatory system increases time and cost for firms. When rules are simpler and processes are digital, firms can focus more on production and less on paperwork. Reforms such as the National Single Window System, decriminalisation of minor economic offences, Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) and the new labour codes aim to create a predictable and business-friendly environment that encourages investment in manufacturing.

Developing skills to match industry needs: Efficient manufacturing requires not just factories but also a skilled workforce capable of operating modern equipment. India is attempting to bridge the skills gap through the Skill India Mission, PMKVY, Jan Shikshan Sansthan, and Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme, which connect industrial clusters with training institutions so that youth acquire practical, job-ready skills.

Focusing on labour-intensive sectors for employment: India has a large workforce, so sectors that can absorb many workers are crucial. Textiles, garments, leather, footwear, toys and food processing can create mass employment if supported properly. Policies like PLI for textiles, PM MITRA mega textile parks, ODOP, and Operation Greens aim to build clusters where firms benefit from shared infrastructure and larger orders.

Ensuring reliable and affordable energy for industry: Manufacturing becomes more efficient when power is cheap and uninterrupted. The Revamped Distribution Sector Scheme (RDSS), push for renewables, and the National Green Hydrogen Mission aim to lower energy costs and improve reliability, helping especially power-intensive industries such as metals, cement and chemicals.

Manufacturing is crucial for India because it can generate large-scale jobs, raise GDP growth, boost exports and technology, and support structural transformation from agriculture to industry, making it central to inclusive and sustainable economic development.

Source: The Hindu

|

Practice Question Q. Discuss the importance of the manufacturing sector in India’s economic development. What key constraints hinder its growth, and how can recent government initiatives address them? (250 words) |

The manufacturing sector is important because it can generate large-scale employment, increase GDP growth, boost exports, promote technological development, and shift surplus labour from low-productivity agriculture to higher-productivity industry.

Manufacturing contributes about 15–17% of India’s GDP, and this share has remained largely stagnant over the past two decades.

The manufacturing sector employs roughly 11–12% of the total workforce, with a majority of workers engaged in small and informal enterprises.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved