India’s carbon credit market, guided by the Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS) 2023, aims to accelerate the country’s transition toward a low-carbon economy and meet its Net Zero 2070 goal. The market allows entities to trade verified emission reductions through renewable energy, afforestation, and sustainable farming projects. However, challenges such as weak verification systems, limited domestic demand, inequitable benefit-sharing, and risks of land displacement persist. Strengthening monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV), ensuring community participation, and improving regulatory transparency are essential for building a fair, credible, and effective carbon market that supports inclusive climate action.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: The Hindu

As India develops its carbon market, it faces a crucial challenge — ensuring that climate action does not come at the cost of farmers’ rights and community well-being. Global experiences show that without proper safeguards, carbon markets can reproduce exploitative systems that marginalize local populations under the banner of sustainability.

A carbon credit represents a verified reduction or removal of greenhouse gases (GHGs), measured in carbon dioxide equivalents (CO₂e).

These credits are generated from:

Companies purchase these credits to offset their emissions while transitioning toward cleaner operations. Ideally, such markets also reward developing nations for adopting sustainable, low-carbon pathways.

Picture Courtesy: PIB

|

Dimension |

Implications / Opportunities |

Key Data / Challenges |

Comparison with Other Nations |

Source |

|

Environmental |

Carbon credits encourage emission reduction through renewable energy, reforestation, and sustainable agriculture. They support India’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement and can significantly lower GHG emissions. |

India’s voluntary carbon projects have issued ~298 million credits, equal to about 10–11% of India’s annual GHG emissions (2021 baseline). However, about 47.7 million credits globally in 2024 were deemed “problematic”; nine Indian projects were flagged for over-crediting. |

The EU ETS remains the most robust compliance carbon market, covering ~36% of EU emissions. China’s ETS, launched in 2021, covers 4.5 billion tonnes CO₂ annually, while India’s domestic market (CCTS) is yet to issue credits. |

Down To Earth (2024); Mongabay-India (2025); arXiv (2023) |

|

Social / Livelihood |

Carbon credit projects create rural employment, incentivize sustainable land use, and promote community-based forestry and agroforestry. They enhance awareness of climate resilience among farmers and local groups. |

NABARD’s pilot in Karnataka engaged 3,500 mango farmers, offering an estimated ₹20,000–₹40,000 per hectare in additional income. Yet, awareness and fair-benefit mechanisms remain weak. |

In Kenya and Uganda, community carbon projects under Verra and Gold Standard provide $15–25 per hectare annually; but like India, delays and unequal benefit distribution persist. |

Times of India (2024); Verra (2023) |

|

Economic / Market |

Carbon credits can channel significant investment into clean energy, waste management, and afforestation. They offer revenue diversification and export potential. |

India has ~1,451 projects, 860 registered, generating ~$652 million in carbon revenue. Exporting credits, however, may limit India’s domestic emission reduction accounting. |

The EU carbon price averaged €68 per tonne in 2024, while India’s voluntary market trades below $8–10 per tonne. The U.S. voluntary market also fluctuates around $10–15 per tonne, showing India’s price gap and scope for growth. |

Down To Earth (2024); Mint (2024); IEA (2024) |

|

Governance / Regulatory / Ethical |

Strong governance is needed for transparency, clear ownership, and MRV (Measurement, Reporting, and Verification). Ethical governance ensures equitable benefit-sharing and prevents “green colonialism.” |

India’s Economic Survey (2023–24) warned that exporting carbon credits could make domestic emission cuts costlier. Many Indian renewable projects have been criticized for limited additionality. |

The EU ETS has stringent verification and auctioning rules, while China’s ETS faces MRV and transparency issues similar to India. Brazil integrates REDD+ credits into national GHG targets — a model India can adopt. |

Mongabay-India (2025); Mint (2024); Carbon Pulse (2024) |

Source: The Hindu

|

Practice Question Q. “India’s carbon credit market has immense potential to drive low-carbon growth, but its success depends on ensuring environmental integrity and social justice.” Discuss. (250 words) |

A carbon credit represents a verified reduction or removal of one metric tonne of carbon dioxide (CO₂) or its equivalent in greenhouse gases (GHGs). It can be bought or sold in carbon markets to offset emissions.

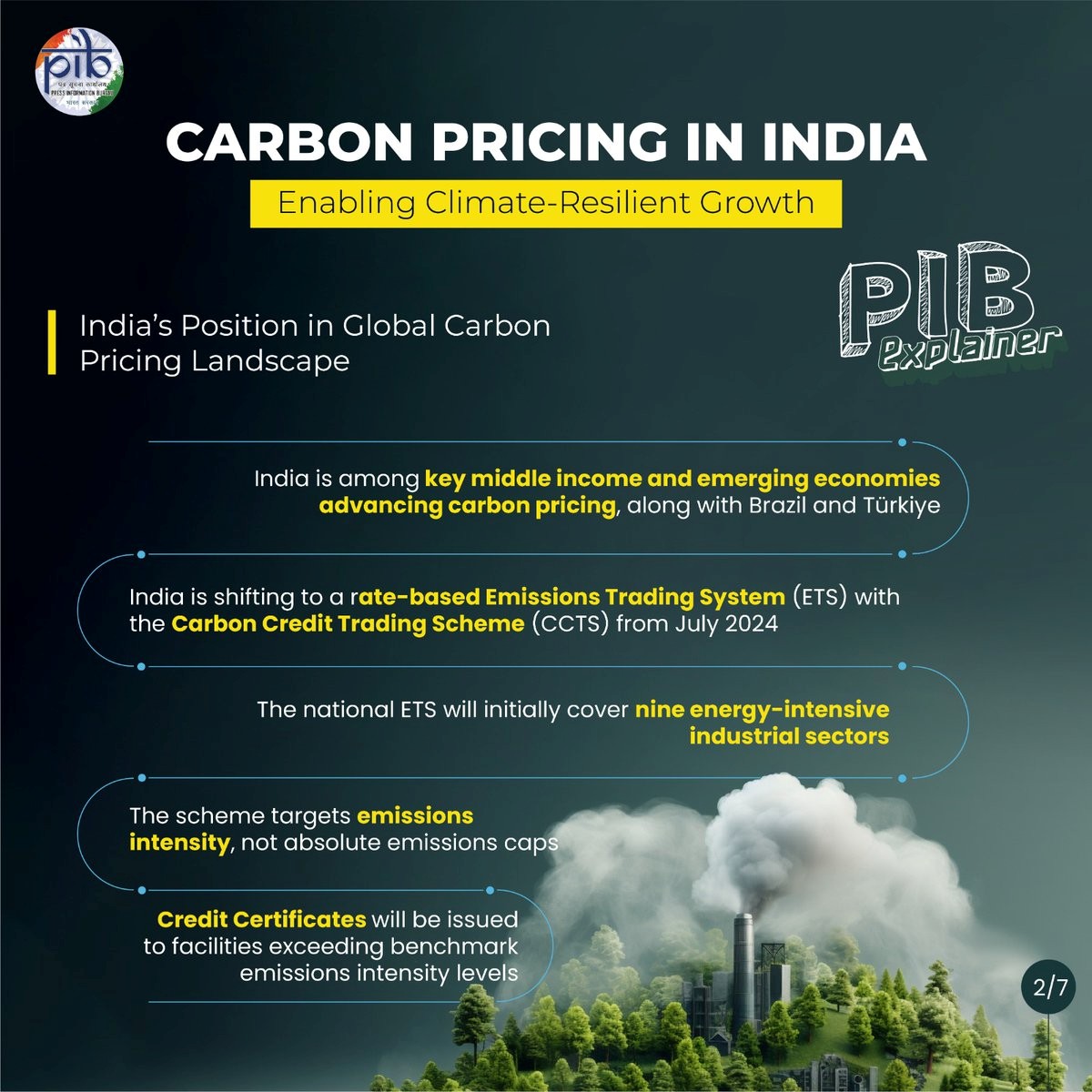

The CCTS, notified in 2023 under the Energy Conservation Act, 2001, is India’s national framework to develop a compliance-based carbon market. It will set emission-intensity benchmarks for key sectors and create a national registry and trading platform managed by the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE) and the Power Ministry.

India’s voluntary projects have issued about 298 million carbon credits, roughly 10–11% of India’s annual GHG emissions (2021 baseline).

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved