Cervical cancer remains a major rural health crisis in India despite being preventable, due to low screening coverage, late diagnosis, weak referral systems, limited access to diagnostic and treatment facilities, and gaps in HPV vaccination. The high burden reflects systemic health inequities rather than medical limitations, underscoring the need for integrated prevention, early detection, and equitable healthcare delivery aligned with global elimination goals.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: Down to earth

Cervical cancer continues to be a major public health challenge in India, particularly in rural and underserved regions. Despite being largely preventable and slow-growing, it remains one of the leading causes of cancer deaths among Indian women.

|

Must Read: REPORT ON CERVICAL CANCER | WHO LAUNCHES STRATEGY TO ACCELERATE ELIMINATION OF CERVICAL CANCER | |

Cervical cancer is a type of cancer that develops in the cervix, the lower part of the uterus that connects the uterus to the vagina. It occurs when normal cervical cells undergo abnormal changes and begin to grow uncontrollably.

The disease is caused almost entirely by persistent infection with high-risk types of Human Papillomavirus (HPV), a very common sexually transmitted virus. While most HPV infections clear naturally, long-term infection with certain strains can lead to cancer.

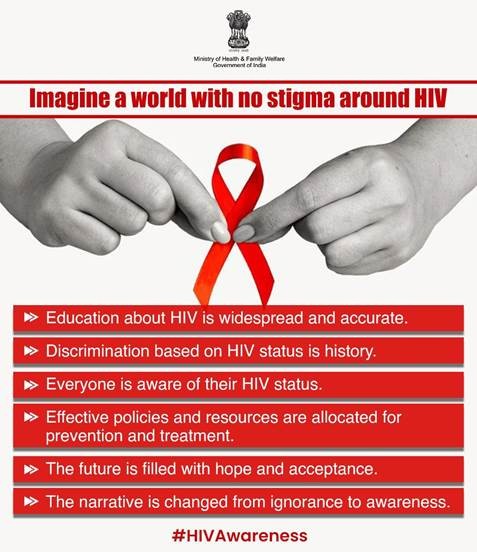

Cervical Cancer and HIV

Women living with HIV face a substantially higher risk of developing cervical cancer due to compromised immune function. Evidence shows they are about six times more likely to develop the disease than women without HIV, and approximately 5% of global cervical cancer cases are attributable to HIV infection.

Because cervical cancer often affects women in their productive and reproductive years, it has wider social consequences. Nearly one-fifth of children who lose a mother to cancer do so as a result of cervical cancer, underscoring its intergenerational impact.

Disease Progression:

Almost all cases of cervical cancer are caused by persistent infection with oncogenic strains of human papillomavirus (HPV), a very common sexually transmitted infection. While most HPV infections are cleared naturally by the immune system, long-term infection with high-risk types can lead to abnormal cellular changes in the cervix.

If left untreated, these precancerous lesions can progress to invasive cancer over 15–20 years. In women with weakened immunity, such as those with untreated HIV, progression can be much faster, sometimes occurring within 5–10 years.

Several factors influence the likelihood of progression, including:

Preventing cervical cancer requires a life-course approach that integrates awareness, vaccination, regular screening, and timely treatment.

HPV vaccination: HPV vaccination for girls aged 9–14 years is highly effective in preventing HPV infection and related cancers. As of 2025, several HPV vaccines are available globally, all of which protect against HPV types 16 and 18, responsible for most cervical cancer cases.

Vaccination schedules vary by country and immune status. While some countries also vaccinate boys to reduce community transmission and prevent HPV-related cancers in men, universal coverage among adolescent girls remains the priority.

Additional preventive measures include avoiding tobacco use, consistent condom use, and voluntary male circumcision.

Cervical screening and management of precancer: Regular screening is essential for detecting precancerous changes before they progress to cancer. Women are advised to begin screening at 30 years of age, while women living with HIV should start earlier, usually at 25 years.

High-performance tests, particularly HPV-DNA testing, are recommended at 5–10 year intervals. Self-sampling has emerged as a reliable and acceptable option, especially for women facing access, privacy, or social barriers.

When screening results are positive, early treatment of precancerous lesions can effectively prevent cervical cancer. Common treatment options include thermal ablation, cryotherapy, loop excision procedures (LEEP/LEETZ), and cone biopsy, where required. These procedures are generally quick, safe, and minimally uncomfortable.

Early Detection and treatment of invasive cancer: Cervical cancer is highly curable when detected early. Awareness of symptoms and prompt medical consultation are crucial. Warning signs may include abnormal vaginal bleeding, persistent pelvic or back pain, unusual discharge, unexplained weight loss, or swelling of the legs.

Diagnosis involves clinical evaluation, imaging, and histopathological testing, followed by stage-appropriate treatment such as surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and supportive or palliative care.

Effective outcomes depend on clear referral pathways and multidisciplinary care, ensuring timely diagnosis, guideline-based treatment, and holistic support addressing physical, psychological, and social needs.

High burden with disproportionate rural impact: India accounts for nearly one-fourth of global cervical cancer deaths. In 2022, the country recorded about 1.27 lakh new cases and nearly 80,000 deaths. Rural women face a significantly higher risk because over 60–70% of cases are detected at advanced stages, compared to earlier-stage detection in urban areas.

Extremely low screening coverage: Despite national programmes, screening remains limited. Population-based surveys and programme data indicate that less than half of eligible women have ever been screened, with some estimates placing routine screening coverage as low as 1.9% among women aged 30–49 years. This directly contributes to delayed diagnosis and high mortality.

Overreliance on VIA with weak follow-up: Most rural screening relies on Visual Inspection with Acetic Acid (VIA). While cost-effective, VIA is operator-dependent and subjective, requiring strong referral systems.

Fact: Studies show that a large proportion of women who test positive on VIA do not receive confirmatory colposcopy or treatment, mainly due to distance, cost, and poor counselling.

Limited access to diagnostic and treatment facilities: Advanced diagnostics such as HPV-DNA testing, colposcopy, biopsy, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy are concentrated in urban tertiary hospitals. Rural women often travel 50–200 km for confirmatory diagnosis or treatment, leading to high out-of-pocket expenditure and loss of daily wages.

Capacity gaps: ASHAs and ANMs are the backbone of outreach, but cancer prevention has been added to their roles without proportional training or time allocation. National Health Mission reviews have highlighted skill gaps in counselling, sample handling, and follow-up, weakening continuity of care.

Low HPV vaccination uptake: Although HPV vaccination is globally recognised as a game-changer, systematic nationwide rollout remains limited in India, especially in rural areas. Lack of awareness, misinformation, and weak school-based delivery systems restrict coverage, reducing long-term prevention impact.

National Programme for Prevention and Control of Cancer, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Diseases and Stroke (NPCDCS): Under the NPCDCS, cervical cancer screening has been integrated into population-based screening for non-communicable diseases. Women aged 30–65 years are screened primarily using Visual Inspection with Acetic Acid (VIA) at the primary care level, with referral linkages to higher facilities for diagnosis and treatment.

Ayushman Arogya Mandirs (Health and Wellness Centres): Upgraded primary healthcare facilities, now known as Ayushman Arogya Mandirs, serve as the frontline for cervical cancer prevention. These centres provide:

As of mid-2025, over 100 million women had been screened under the population-based NCD programme, though rural gaps persist.

National Health Mission (NHM) support: The National Health Mission provides financial and operational support to states for:

Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY): Under PM-JAY, eligible beneficiaries receive cashless treatment for cervical cancer at secondary and tertiary hospitals. This reduces catastrophic health expenditure for poor households requiring surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy.

WHO global strategy for Cervical Cancer elimination: In 2020, the World Health Organization launched the Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer, marking the first coordinated global effort to eliminate a cancer.

It is built around the 90–70–90 targets by 2030:

Achieving these targets could prevent over 60 million deaths globally by the end of the century.

UN Joint Global Programme on Cervical Cancer: Multiple UN agencies including WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, and UN Women collaborate under a joint global programme to:

This approach recognises cervical cancer as both a health and gender equity issue.

Australia is on track to eliminate cervical cancer by the 2030s due to near-universal HPV vaccination and HPV-based screening.

Rwanda achieved over 90% HPV vaccination coverage through strong political commitment and school-based delivery.

Bhutan combined HPV vaccination with organised screening, demonstrating success in a low-resource setting.

Cervical cancer remains a major yet preventable health challenge, particularly in rural and low-resource settings. Its continued high burden reflects gaps in vaccination, screening, timely diagnosis, and equitable access to treatment rather than limitations of medical knowledge. Aligning national efforts with global strategies—especially universal HPV vaccination, high-quality screening, and strengthened referral systems—can transform cervical cancer from a leading cause of death into a disease of the past.

Source: Down to Earth

|

Practice Question Q. Cervical cancer is increasingly described as a public health failure rather than a medical challenge in India. In this context, examine why cervical cancer continues to remain a rural health crisis despite the availability of preventive and curative measures. Suggest a comprehensive way forward in line with global best practices. (250 words) |

Cervical cancer can be prevented through HPV vaccination, regular screening, and early treatment of precancerous lesions, as the disease progresses slowly over many years.

Rural women face low screening coverage, late diagnosis, weak referral systems, limited access to diagnostic and treatment facilities, and socio-cultural barriers, leading to higher mortality.

VIA is a subjective test and requires strong follow-up and referral systems. In many rural areas, women who test positive do not receive timely confirmatory diagnosis or treatment.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved