Masala Bonds are rupee-denominated bonds issued abroad to raise capital without exposing Indian issuers to currency risk. After early momentum, the market declined due to rising global interest rates, rupee depreciation, stricter RBI norms, weak offshore INR liquidity, and better domestic borrowing options. In Kerala’s case, KIIFB’s 2019 masala bond has come under ED scrutiny for alleged FEMA and RBI guideline violations, particularly related to end-use restrictions. With politics intensifying ahead of elections, the issue reflects larger debates on off-budget borrowing, fiscal autonomy, and the evolving role of rupee internationalisation in shaping India’s external financing landscape.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: The Hindu

The Kerala Infrastructure Investment Fund Board (KIIFB)—the State’s main funding arm for large infrastructure projects—had raised money through a Masala Bond in 2019.

In November 2025, the Enforcement Directorate (ED) issued show-cause notices for alleging violations of FEMA and RBI rules in connection with the bond.

|

Background of the Story In 2019, the Kerala Infrastructure Investment Fund Board (KIIFB) raised ₹2,150 crore through a Masala Bond listed abroad to finance State infrastructure. Although the entire amount was repaid by March 2024, the transaction has remained controversial. The Enforcement Directorate (ED) is now examining whether KIIFB violated FEMA and RBI’s External Commercial Borrowing rules, particularly the alleged use of ₹466.91 crore for land purchases—an activity prohibited under masala bond regulations. Earlier, the CAG had questioned the RBI’s approval for the bond and flagged concerns about Kerala’s expanding off-budget borrowings through KIIFB. With the 2025 local body elections approaching, the issue has resurfaced, intensifying political accusations between the LDF government and the Opposition. |

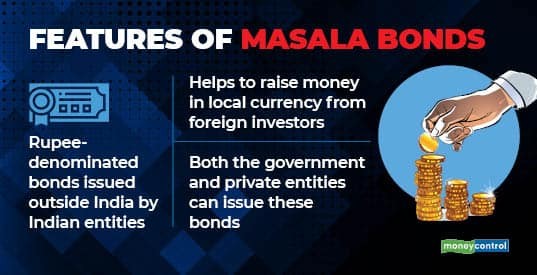

Masala bonds are rupee-denominated debt instruments issued in foreign markets by Indian entities.

They allow borrowers in India to raise money overseas in Indian rupees, not in foreign currency.

The first such bond was issued in October 2013 by the International Finance Corporation (IFC)—a World Bank Group institution—under its USD 2-billion offshore rupee programme.

Picture Courtesy: Money control

Key Features:

Rupee-Denominated: The bonds are issued overseas but priced and repaid in Indian rupees, not in foreign currency.

Currency Risk on Investor: Any exchange-rate fluctuation is borne by foreign investors, reducing currency risk for Indian issuers.

Issued Abroad: Indian entities issue these bonds in international financial markets—often listed on exchanges like London or Singapore.

Eligible Issuers: Both government bodies (e.g., KIIFB) and private companies can issue them with RBI approval.

Wider Investor Base: Investors from FATF-compliant countries, IOSCO-regulated markets, and multilateral agencies can participate.

Attractive Interest Rates: To offset higher currency risk, masala bonds usually carry higher yields than comparable bonds in investors’ home markets.

Depreciating rupee increased investor risk: Masala bonds lost traction because they are rupee-denominated, meaning foreign investors bear the full currency risk, and the ₹ depreciated by nearly 18% between 2018 and 2020.

Higher cost of borrowing reduced issuer interest: As global interest rates hardened between 2022–24, issuers had to offer higher coupon rates to compensate for currency risk, often exceeding 9–10%, compared to 7–8% available in India’s improving domestic bond market.

RBI’s tightened regulatory framework discouraged new issuances: RBI strengthened its ECB and Masala Bond guidelines by imposing stricter end-use norms (such as prohibiting land purchase), mandating a minimum maturity of 3–5 years, and enhancing compliance scrutiny.

Stronger domestic bond market made offshore issuances redundant: India’s corporate bond market deepened significantly, with annual corporate bond issuance crossing ₹40 lakh crore by 2023, offering cheaper and more liquid options for funding.

Companies like HDFC, which had earlier tapped masala bonds in 2016 and 2017, subsequently shifted entirely to domestic bonds as yields became more competitive and regulatory processes were simpler.

Post-COVID global risk aversion shifted investors away: After the COVID-19 shock and global monetary tightening, foreign investors moved away from emerging market local-currency debt, causing rupee-risk instruments like masala bonds to lose investor demand.

Reduced need for rupee-denominated borrowing abroad: As India promotes the internationalisation of the rupee (INR) through rupee trade settlement, Vostro accounts, and bilateral currency arrangements, foreign investors and trading partners now have more avenues to hold and transact in INR.

Shift toward direct rupee trade lowers investor dependence on bonds: With more countries (e.g., Russia, UAE, Sri Lanka, Mauritius) settling trade in rupees, foreign institutions gain natural INR exposure, reducing the need to buy external rupee bonds like masala bonds to access rupee assets.

Greater INR stability reduces the original purpose of Masala bonds: Masala bonds were attractive because they transferred currency risk to investors.

As India’s push for INR internationalisation stabilises the rupee through higher global demand, stronger forex buffers, and multiple rupee-settlement corridors,

Global INR liquidity remains limited, restricting Masala bond growth: Even with internationalisation efforts, rupee liquidity outside India is still thin compared to USD or EUR.

Masala bonds require a deep offshore INR market, which has not yet fully developed. For example, the London Stock Exchange masala bond market, once seen as a major growth driver, saw almost no large new issuances after 2020 due to low offshore INR liquidity.

Masala bonds began as a promising tool to attract global capital into India’s rupee market, but rising currency risk, high borrowing costs, stricter regulations, and stronger domestic financing options led to their rapid decline. With the internationalisation of the rupee and improved onshore bond markets, the relevance of masala bonds has steadily diminished, leaving them as a niche instrument rather than a mainstream borrowing avenue.

Source: The Hindu

|

Practice Questions Q. “Masala Bonds, once viewed as a tool to attract global capital into India's rupee market, have lost momentum in recent years.” Discuss the factors behind their decline and analyse how rupee internationalisation is reshaping their relevance. (250 Words) |

Masala Bonds are rupee-denominated bonds issued in foreign markets by Indian entities to raise funds without taking on foreign exchange risk.

The term “Masala” was introduced to give these offshore rupee bonds a distinct Indian identity, similar to how “Dim Sum Bonds” (China) or “Samurai Bonds” (Japan) are named.

Both corporates and government-linked entities such as PSUs and State financial agencies (e.g., KIIFB) can issue these bonds with RBI approval.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved