The article argues that global and national climate policies remain overly focused on forests while neglecting grasslands, despite their critical role as stable carbon sinks, biodiversity reservoirs, and livelihood systems for indigenous and pastoral communities. It highlights how institutional silos between climate, biodiversity, and land-degradation frameworks have marginalised grasslands, using examples from Australia, Brazil’s Cerrado, and India. The piece calls for integrating grasslands into national climate plans and NDCs, recognising community land rights, and building coordination among UN bodies to ensure effective, science-based, and socially just climate action.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: The Hindu

UN has declared 2026 as the International Year for Rangelands and Pastoralists. Global debate on forest-centric climate policies ignoring grasslands and savannahs. COP30 (Belém, Brazil) again focused largely on forests, sidelining other biomes.

|

Must Read: BANNI GRASSLANDS | WORLD SOIL DAY,2025 | Rangelands | KAZIRANGA | |

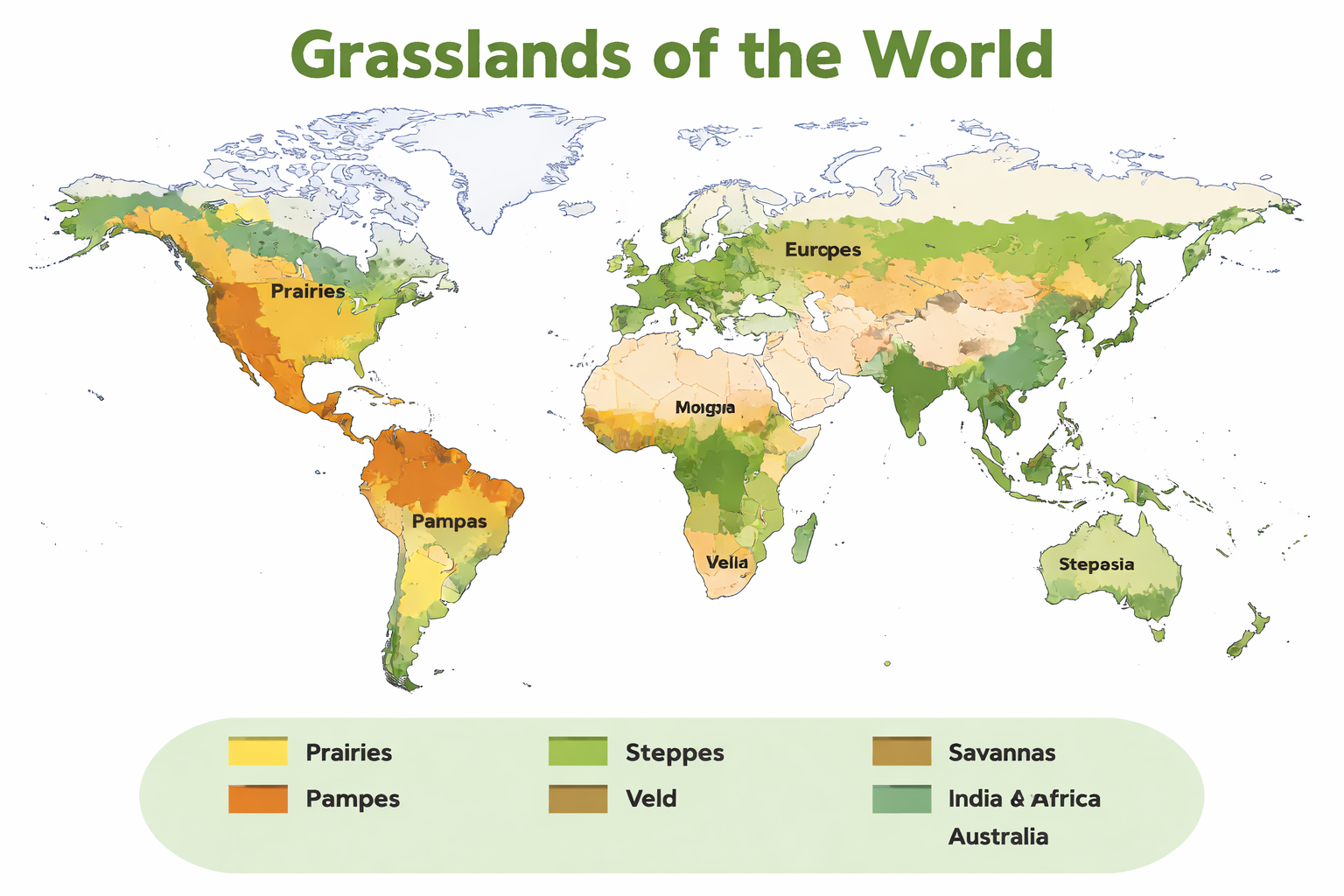

Grasslands are terrestrial ecosystems dominated by grasses and herbaceous plants, with few or no trees, occurring in regions where rainfall is moderate but insufficient to support dense forests.

Key characteristics:

Tropical Grasslands (Savannas): These grasslands occur mainly between forests and deserts in tropical regions and are characterised by grasses with scattered trees, such as the African savanna and the Brazilian Cerrado.

Temperate Grasslands: Found in mid-latitude regions, these grasslands include the Prairies of North America, the Steppes of Eurasia, and the Pampas of South America, and are known for extensive grass cover and fertile soils.

Montane and Alpine Grasslands: These grasslands occur at high altitudes and cold climates, such as the Himalayan alpine meadows and the Shola grasslands of the Western Ghats, and support specialised flora and fauna.

Tropical and Semi-Arid Grasslands: These grasslands occur in regions with low to moderate rainfall and are widespread across western, central, and peninsular India, particularly in Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, and Telangana, supporting pastoral livelihoods and species like the Great Indian Bustard.

Savanna-type Grasslands: Savanna grasslands with scattered trees are found in parts of central India and the Deccan Plateau, where seasonal rainfall and grazing maintain open grassy landscapes interspersed with shrubs and trees.

Alluvial Floodplain Grasslands: These grasslands develop along major river systems such as the Ganga–Brahmaputra plains, especially in Assam and northern Bihar, and include the tall wet grasslands of Kaziranga and Manas, which are crucial for rhinoceros, elephants, and swamp deer.

Montane Grasslands: Montane grasslands occur at higher elevations in the Western Ghats, Eastern Ghats, and parts of central India, often forming mosaics with forests and playing an important role in water regulation.

Alpine Grasslands: Alpine grasslands are found above the tree line in the Himalayas—including Jammu & Kashmir, Ladakh, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Sikkim, and Arunachal Pradesh—and are characterised by short grasses, herbs, and seasonal flowering meadows.

Shola Grasslands: Shola grasslands are unique montane grassland–forest mosaics of the upper Western Ghats (Nilgiris, Anamalai, Palani hills), where rolling grasslands alternate with patches of evergreen shola forests.

Desert Grasslands: Desert grasslands occur in the Thar Desert of Rajasthan and parts of Gujarat, dominated by drought-resistant grasses and shrubs, and are adapted to extreme aridity and temperature variations.

|

International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists (2026) Declaration and Leadership: The United Nations General Assembly has designated 2026 as the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists, with the initiative being coordinated by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). What Are Rangelands: Rangelands include grasslands, savannahs, shrublands, and deserts, forming open ecosystems that play a crucial role in maintaining ecological balance. Global Extent and Human Dependence: Rangelands occupy more than half of the Earth’s terrestrial surface and provide the primary livelihood base for over 500 million pastoralists who depend on these landscapes for livestock rearing. Climate Significance: These ecosystems are essential for biodiversity conservation, ecosystem regulation, and climate resilience, particularly in dryland and semi-arid regions vulnerable to climate change. Objectives of the International Year: The initiative aims to increase global awareness, encourage responsible and sustainable investments, protect pastoralists’ land tenure and mobility rights, promote inclusive governance systems, and improve rangeland management practices. |

Legal gaps: Grasslands in India lack a clear legal definition as distinct ecosystems and are often misclassified as “wastelands”, resulting in their diversion for afforestation, agriculture, infrastructure, and industrial use.

Low protection coverage: Less than 5% of India’s grasslands fall within legally protected areas, compared to forests which receive the bulk of conservation funding and legal safeguards, leaving most grasslands vulnerable to conversion and degradation.

Forest-centric conservation approach: National climate and conservation policies remain forest-biased, with grasslands often targeted for tree plantations under carbon sequestration and afforestation schemes, despite scientific evidence that such actions degrade native grassland biodiversity and soil carbon.

Institutional fragmentation: Grasslands fall under the jurisdiction of multiple ministries and departments (around 18 in India)—including environment, agriculture, rural development, and animal husbandry—leading to overlapping mandates, policy conflicts, and weak coordination.

Weak data, mapping, and monitoring: India lacks high-resolution, nationwide mapping and long-term ecological monitoring of grasslands, resulting in poor baseline data on grassland extent, health, carbon stocks, and biodiversity trends.

Neglect of indigenous and pastoral knowledge: Traditional grazing systems and controlled burning practices of pastoral and indigenous communities are often restricted or criminalised, despite evidence that such practices historically maintained grassland productivity and ecological balance.

Land-use change and development pressures: Rapid conversion of grasslands for agriculture, solar and wind energy parks, mining, roads, and urban expansion has led to widespread habitat fragmentation, particularly affecting grassland-dependent species.

Invasive species and poor management: Invasive species such as Prosopis juliflora and Lantana camara have spread across Indian grasslands, while limited resources and technical capacity hinder effective restoration and invasive control.

Climate policy exclusion: Grasslands are largely absent from India’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and national climate strategies, despite their potential role in soil carbon sequestration, drought resilience, and adaptation.

Biodiversity blind spot: Conservation prioritisation tends to favour charismatic forest species, while grassland specialists—such as bustards and floricans—receive limited attention, even though over half of India’s grassland birds are declining.

Strengthening grassland conservation in India requires legal recognition, ecosystem-appropriate policies, effective use of existing government initiatives, and active involvement of pastoral communities to safeguard biodiversity, livelihoods, and climate resilience.

Source: The Hindu

|

Practice Questions Q. “Climate action has remained forest-centric, often overlooking grasslands despite their ecological and carbon sequestration potential.” Discuss. (250 words) |

Grasslands store 70–90% of their carbon below ground in soils and roots, making them stable carbon sinks and resilient to fires, droughts, and climate extremes.

Climate negotiations under the UNFCCC are largely carbon-centric and forest-focused, while grasslands fall between the mandates of climate, biodiversity, and land degradation conventions.

COP30 primarily focused on forests, particularly the Amazon, with grasslands receiving attention mainly through side events, civil society advocacy, and indigenous protests, rather than formal negotiations.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved