India plans to open civil nuclear power to private players to reach 100 GW by 2047. The shift aims to ease financing gaps and speed up projects. Progress depends on removing hurdles in the CLND Act and amending the Atomic Energy Act through the proposed 2025 Bill.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: BUSINESS-STANDARD

The Prime Minister announced that India would open the civil nuclear sector to private players.

|

Read all about: Private Sector Participation in the Nuclear Energy Sector l Nuclear Sector Opens to Private l Private Sector in Nuclear Energy l India Opens Up Nuclear Sector |

Nuclear energy is a non-fossil fuel source, generated through nuclear fission, providing reliable and low-carbon electricity.

Nuclear power is the fifth-largest source of electricity in India after coal, hydro, solar and wind.

Historically, India's nuclear sector has been exclusively controlled by the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE), with the Nuclear Power Corporation of India Ltd (NPCIL) as the sole operator of commercial reactors.

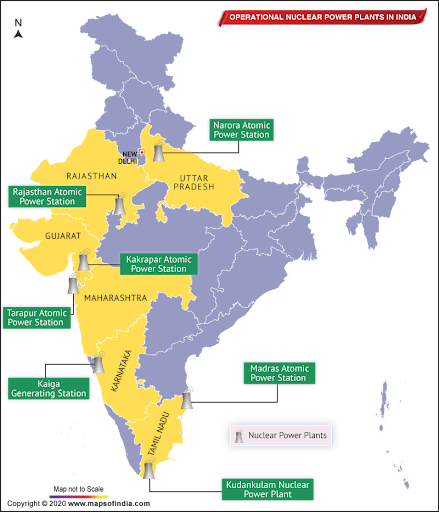

As of April 2025, India has 25 nuclear reactors in operation in 7 nuclear power plants, with a total installed capacity of 8,880 MW. Target for 22,480 MW by 2031-32 and 100 GW by 2047. (Source: PIB)

Bridging the Financing Gap: Achieving the 100 GW target by 2047 requires an estimated investment of $217 billion (Source: NucNet). Public funds alone are insufficient to meet this capital requirement.

Accelerating Capacity Addition: Private sector efficiency can help overcome historical delays and expedite project timelines.

Meeting Energy Demand: India's energy demand is projected to grow faster than any other major economy. Nuclear power provides clean, reliable, and baseload power to support this growth.

Achieving Climate Goals: Nuclear energy is essential for meeting India's commitments of 500 GW non-fossil fuel capacity by 2030 and achieving Net-Zero emissions by 2070.

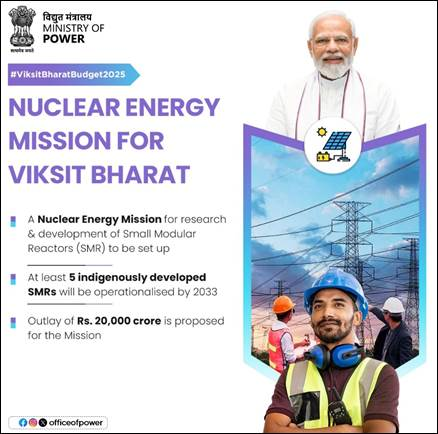

Promoting Technological Innovation: Private investment will boost R&D, especially in Small Modular Reactors (SMRs), a key focus of the Nuclear Energy Mission.

Enabling private participation requires reforms to the existing legal framework, which the government is actively pursuing.

Required Legislative Amendments

Atomic Energy Act, 1962: This act currently establishes a state monopoly and prohibits private companies from owning and operating nuclear power plants.

Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage (CLNDA) Act, 2010: This law's Section 17 gives operators "right of recourse" against suppliers after an accident, a deviation from international conventions placing sole liability on the operator. This deters foreign and private suppliers.

Proposed Participation Models

The government is exploring various models to integrate private players, drawing lessons from the successful liberalization of the space sector.

Liability Framework: The CLNDA, 2010 remains the single biggest deterrent for both domestic and international private players due to its supplier liability clauses.

High Capital Costs & Long Gestation: Nuclear projects are capital-intensive with long construction periods, creating financial risks that require robust financial models like viability gap funding or sovereign guarantees.

Regulatory Capacity: The Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB) will need strengthening in terms of autonomy and resources to effectively oversee multiple private operators while ensuring stringent safety standards.

Fuel Supply: India has limited domestic uranium reserves and relies on imports. Private players are currently not allowed to mine or process nuclear fuel, creating a dependency on state-owned entities.

Public Perception: Ensuring public trust and addressing concerns related to nuclear safety and waste management is crucial for the social acceptance of new projects.

Several major economies have successfully integrated private players into their nuclear energy sectors, offering potential models for India.

|

Country |

Model of Private Participation |

|

United States |

Private companies own and operate commercial nuclear plants. The government actively supports private innovation in advanced reactors like SMRs through programs like the Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program (ARDP). Tech giants like Microsoft and Google are also investing in nuclear power. |

|

United Kingdom |

The UK's strategy involves private investment in new large-scale reactors and SMRs, often de-risked with government guarantees and support. |

|

Canada |

Hosts private nuclear generators like Bruce Power, which operates multiple reactors and is a major contributor to Ontario's electricity supply. |

|

France |

Dominated by the state-controlled but publicly-listed company Électricité de France (EDF), which operates as a commercial entity and is a global leader in nuclear technology. |

Private sector inclusion in nuclear energy is a vital step for India's future, requiring a clear and stable government policy environment for success.

Legislative Amendments: Amend the Atomic Energy Act, 1962, to legally permit private sector ownership and operation of nuclear plants. The proposed Atomic Energy Bill, 2025, is a step in this direction.

Reforming the CLND Act: To build investor confidence, the CLND Act, 2010, should be revised to align with international norms like the Convention on Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage (CSC) by limiting supplier liability.

Creating a Clear Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Model: Establish a transparent and viable PPP framework that clearly defines risk-sharing mechanisms, tariff structures, and long-term PPAs.

Developing a Robust SMR Ecosystem: Focus on the Nuclear Energy Mission by fast-tracking R&D and creating a supportive regulatory framework for the deployment of SMRs, which offer lower costs and quicker construction timelines.

Strengthening Fuel Security: Diversify uranium import sources by strengthening diplomatic ties with supplier nations like Australia and Namibia while simultaneously exploring and developing domestic reserves.

Unlocking private capital for India's nuclear power sector to achieve the 100 GW clean energy target by 2047 requires timely legislative reforms addressing liability and ownership to create a predictable and financially attractive investment ecosystem.

Source: BUSINESS-STANDARD

|

PRACTICE QUESTION Q. Examine the governance and regulatory challenges that may emerge with the introduction of private players into the nuclear energy domain. 150 words |

India is allowing private participation to bridge the massive financing gap (estimated at Rs 15 lakh crore) and leverage private sector efficiency to meet its ambitious target of increasing nuclear capacity from 8.88 GW to 100 GW by 2047, which is crucial for its energy security and net-zero goal

The primary legal barrier is the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage (CLND) Act, 2010, particularly Section 17(b), which imposes a potential for unlimited and prolonged liability on suppliers. The Atomic Energy Act, 1962, currently prohibits private entities from owning and operating nuclear plants.

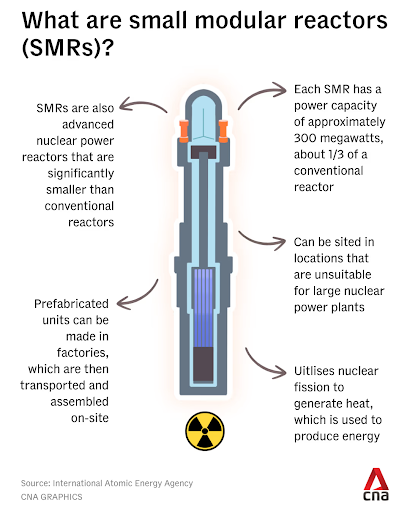

Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) are advanced nuclear reactors that are smaller in size and power output compared to conventional reactors. They are factory-built, scalable, and have enhanced safety features, making them suitable for a wider range of applications and easier to deploy.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved