Disclaimer: Copyright infringement not intended.

Context

- The Union Cabinet chaired by Prime Minister Narendra Modi approved the amendments to the National Policy on Biofuels 2018.

Biofuels

- Biofuels are liquid or gaseous fuels primarily produced from biomass —that is, plant or algae material or animal waste.

- Biofuels can be used to replace or can be used in addition to diesel, petrol or other fossil fuels for transport, stationary, portable and other applications.

- Ethanol and biodiesel are the two main transport biofuels. These fuels can be produced from a variety of biomass.

Categories of biofuels

- First generation biofuels - First-generation biofuels are made from sugar, starch, vegetable oil, or animal fats using conventional technology. Common first-generation biofuels include Bioalcohols, Biodiesel, Vegetable oil, Bioethers, Biogas.

- Second generation biofuels - These are produced from non-food crops, such as cellulosic biofuels and waste biomass (stalks of wheat and corn, and wood). Examples include advanced biofuels like biohydrogen, biomethanol.

- Third generation biofuels - These are produced from micro-organisms like algae.

- Fourth generation biofuels - These are produced from genetically modified (GM) algae to enhance biofuel production.

Note: The prices of both sugarcane and bio-ethanol are set by the central government.

India’s Biofuel Economy

- India is one of the fastest growing economies and the third largest consumer of primary energy in the world after the US and China.

- India’s fuel energy security will remain vulnerable until alternative fuels are developed based on renewable feedstocks.

- The government of India targets reducing the country’s carbon footprint by 30-35% by the year 2030.

- These targets will be achieved through a five-pronged strategy which includes:

- Increasing domestic production

- Adopting biofuels and renewable

- Implementing energy efficiency norms

- Improving refinery processes and

- Achieving demand substitution.

- The government of India has proposed a target of 20% blending of ethanol in petrol and 5% blending of biodiesel in diesel by 2030 and introduced multiple initiatives to increase indigenous production of biofuels.

Biodiesel and its benefits

- Bio-diesel is an eco-friendly, alternative diesel fuel prepared from domestic renewable resources vegetable oils (edible or non- edible oil) and animal fats.

- These natural oils and fats are primarily made up of triglycerides. These triglycerides when reacted chemically with lower alcohols in presence of a catalyst result in fatty acid esters. These esters show striking similarity to petroleum derived diesel and are called "Biodiesel".

- As India is deficient in edible oils, non-edible oil may be material of choice for producing biodiesel. Examples are Jatropha curcas, Pongamia, Karanja, etc.

The benefits of using biodiesel are as follows:

- It reduces vehicle emission which makes it eco-friendly.

- It is made from renewable sources and can be prepared locally.

- Increases engine performance because it has higher cetane numbers as compared to petro diesel.

- It has excellent lubricity.

- Increased safety in storage and transport because the fuel is nontoxic and bio degradable (Storage, high flash pt)

- Production of bio diesel in India will reduce dependence on foreign suppliers, thus helpful in price stability.

- Reduction of greenhouse gases at least by 3.3 kg CO2 equivalent per kg of biodiesel.

Benefits of India’s ethanol blending mandates include:

- Reduce Import Dependency: Will save Foreign Exchange (FOREX).

- Cleaner Environment: Reducing crop burning and converting agricultural residues/wastes to biofuels will further reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

- Health Benefits:Prolonged reuse of cooking oil for preparing food, particularly in deep-frying, is a potential health hazard and can lead to many diseases. Used cooking oil (UCO) is a potential feedstock for biodiesel and its use for making biodiesel prevents reuse of UCO within the food industry.

- Solid Waste Management: There are technologies available, which can convert solid waste and plastics to drop-in fuels.

- Infrastructural Investment in Rural Areas:Establishing additional 2G biorefineries across the country will spur infrastructural investment in rural areas.

- Employment Generation:2G biorefinery can contribute 1200 jobs across plant operations, village level entrepreneurs and supply chain management.

- Additional Income to Farmers:By adopting 2G technologies, agricultural residues/wastes that otherwise are burnt can be converted to ethanol. Farmers can realise an additional revenue source if markets are developed for these residues/wastes.

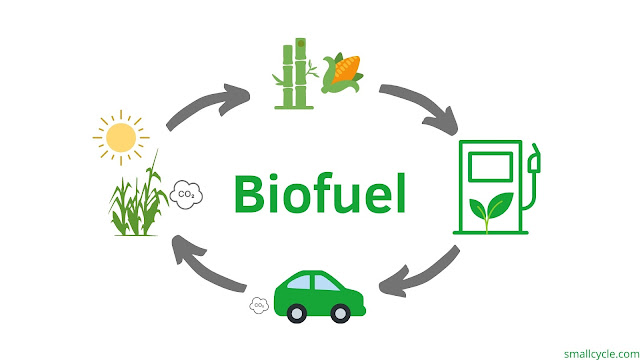

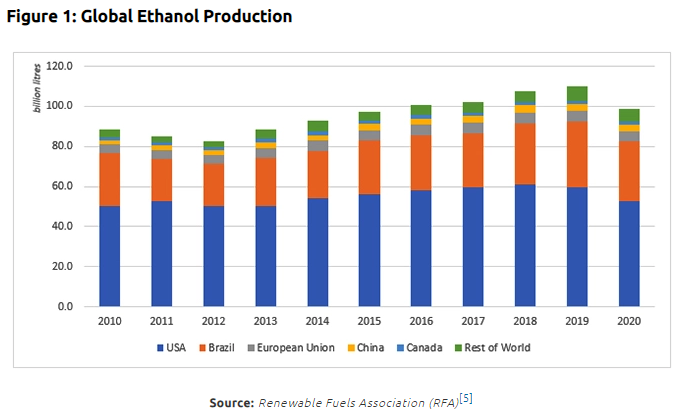

Bio-fuels: Global Scenario

- In the global transport-fuel demand, the share of biofuels remains minimal, accounting for only 2.4 percent in 2018.

- To improve the situation, many countries have implemented dedicated biofuel policies with time-bound blending mandates, incentivising the setting up of distilleries and encouraging the production of energy crops.

- Brazil’s RenovaBio programme is amongst the most ambitious and has resulted in a national ethanol blending rate of 27 percent.

- Both the EU and China have devised a roadmap to achieve a 10 percent ethanol blending rate.

- In the US, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is mandated by law to set production mandates for biofuels, which are regularly updated.

- In terms of feedstock, the global transport biofuel market is heavily dependent on 1G production methods, with 2G methods and lignocellulosic feedback producing less than 10 percent of the total share. In Brazil, ethanol is produced almost exclusively from sugarcane, accounting for 95 percent of the total production and biodiesel is produced mainly from soybean oil. In the

- US, ethanol production is mainly dependent on maize, and 40 percent of the country’s total maize production is used for ethanol production. A more diverse mix of feedstock exists for biodiesel, with soybean oil and other waste oils/fats together accounting for 46 percent of the total production.

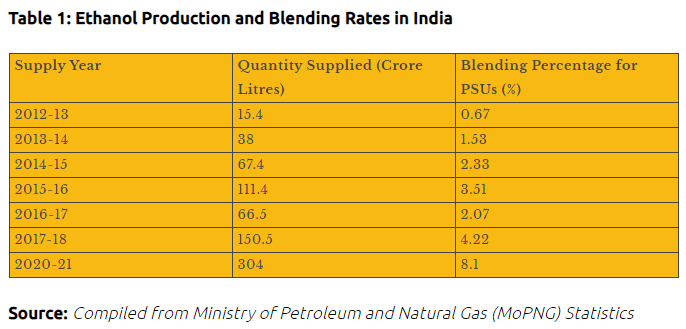

Major programs supporting the development of biofuels production and use in India

Background

- In India, the Ethanol Blending Programme in 2003 was the first significant policy step related to liquid biofuels. It mandated a five-percent blending rate for ethanol in petrol.

- The Biofuel Policy, implemented in 2009, was more ambitious, mandating a 20-percent blending rate for both ethanol and

by 2017. The 2009 policy also moved beyond molasses-based ethanol production to the direct use of sugarcane juice.

- The 2009 Policy also outlined a clear pathway for biodiesel production, utilising non-edible oils—specifically, Jatropha Curcus.

- Despite these measures, ethanol production remained low in the ensuing years. Issues in the sugarcane supply chain prevented production, and oil-marketing companies were unable to get bids for most of the amount offered for purchase.

- This prompted a slew of measures in the next few years, including the reintroduction of administered minimum support price and the opening up of alternate routes for ethanol production.

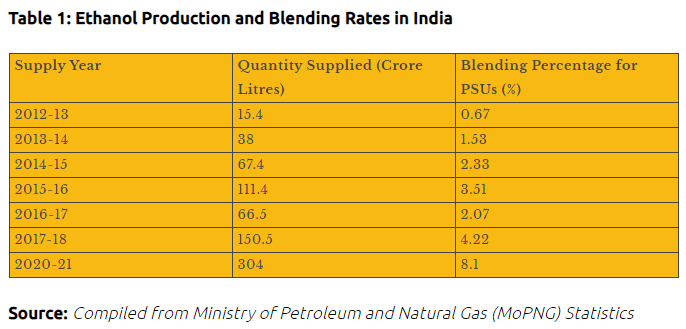

- By 2018, blending rates reached around four percent, followed by a faster uptake in the subsequent years.

‘Pradhan Mantri JI-VAN (Jaiv lndhan- Vatavaran Anukool fasal awashesh Nivaran) Yojana’

- Viable gap funding (VGF)for commercial scale 2G ethanol plants under ‘Pradhan Mantri JI-VAN.

- It is a tool to create 2G ethanol capacity in the country and attract investments in this new sector.

- Financial assistance for demonstration scale 2G integrated bioethanol under Pradhan Mantri JI-VAN Yojana.

- Grants for research and development from Direct Benefit Transfer to 5 Centres for Excellence in the Bioenergy area.

Biogas Power Generation and Thermal Energy Application Programme (BPGTP)

- The programme promotes biogas based Decentralized Renewable Energy Sources of power generation (Off-Grid), in the capacity range of 3 kW to 250 kW or thermal energy for heating/cooling applications from the biogas generation produced from Biogas plants of 30 M3 to 2500 M3 size.

New National Biogas and Organic Manure Programme (NNBOMP)

- The objective is to provide clean cooking fuel for kitchens, lighting and meeting other thermal and small power needs of farmers/dairy farmers/users including individual households and to improve organic manure system based on bio-slurry from biogas plants in rural and semi-urban areas by setting up of small size biogas plants of 1 to 25 Cubic Metre capacity.

Sustainable Alternative Towards Affordable Transportation (SATAT)

- The government is promoting the use of Compressed Bio Gas (CBG) also known as BioCNG. In a significant push that has the potential to boost the availability of more affordable transport fuels, better use of agricultural residue, cattle dung and municipal solid waste as well as to provide an additional revenue source to farmers, an innovative initiative titled SATAT i.e., Sustainable Alternative Towards Affordable Transportation initiative was brought up in

- Under this initiative, Oil PSUs IOCL, HPCL, BPCL, GAIL and IGL have invited Expression of interest (Eol) from potential entrepreneurs to procure CBG.

Ethanol Blended Petrol (EBP)

- On the occasion of World Environment Day, 2021, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, launched the ambitious E100 pilot project in Pune for the production and distribution of ethanol across the country,. The aim is to promote biofuels for a better environment.

- The government resolved to meet the target of 20 per cent ethanol blending in petrol by 2025. Earlier the target was set for 2030. Currently, the ethanol blending level in petrol is around 8.5 per cent.

Financial assistance

- Government has notified scheme for extending financial assistance to project proponents for enhancement of ethanol distillation capacity or to set up distilleries for producing first Generation (1G) ethanol from feed stocks such as cereals (rice, wheat, barley, corn & sorghum), sugarcane, sugar beet etc. vide notification dated January 1, 2021.

- Under the scheme, government would bear interest subvention for five years, including one year moratorium, against the loan availed by project proponents from banks @ 6 per cent per annum or 50 per cent of the rate of interest charged by banks, whichever is lower.

- This loan would be for setting up of new distilleries; expansion of existing distilleries; converting existing distilleries to dual feedstock; setting up of new dual feed distilleries; expansion of existing dual feed distilleries; and installation of Molecular Sieve Dehydration (MSDH) column etc.

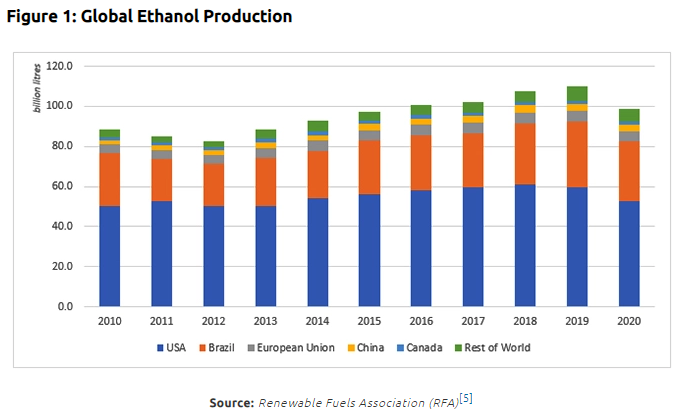

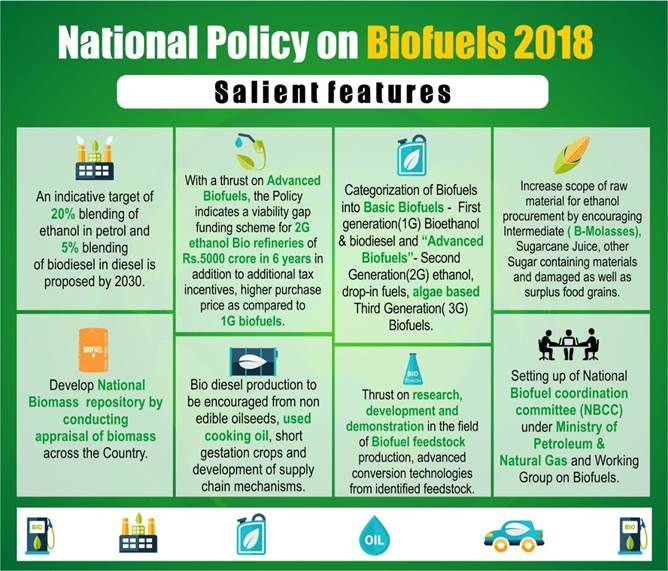

National Policy on Biofuels - 2018

- The 'National Policy on Biofuels 2018' was notified by the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas in 2018 in supersession of National Policy on Biofuels, promulgated through the Ministry of New & Renewable Energy in 2009.

- It provided an indicative target of blending 20% ethanol in petrol by 2030.

- NITI Aayog "Roadmap for Ethanol Blending in India 2020-25" report outlines the journey for 20% ethanol blending in the country.

The policy was drafted to help in meeting the target of reducing import dependence on fossil fuels by 10 per cent from 2014- 15 levels by the year 2022. This target is to be achieved by adopting a five-pronged strategy which includes, increasing domestic production, adopting biofuels & renewable, energy efficiency norms, improvement in refinery processes and demand substitution.

As of 2021, the Government of India claims a blending rate of 8.1 percent

Amendments approved to the National Policy on Biofuels, 2018

- In 2021-22, there has been a pivot from the policy articulated in 2018. The GOI has announced a scaling up of its ethanol blending ambitions—most notably, the deadline for achieving a 20 percent blending rate for ethanol has been set at 2025.

- To enable faster transition, the Union government has doubled down on 1G biofuels.

- In addition to sugar-based production, the use of food grains has been allowed, which includes maize as well as surplus rice from Food Corporation of India (FCI) stocks.

- The loan interest subvention scheme has also been expanded, to include grain-based distilleries apart from sugar or molasses-based distilleries.

- The recently constituted “Expert Committee on Roadmap for Ethanol Blending in India by 2025,” has outlined a reconfigured approach to meeting the new targets that requires 5 billion litres of ethanol to be produced by 2025—a sixfold increase from the 2.7 billion litres produced in 2021.

- The plan is to obtain 6.8 billion litres from sugarcane and 6.6 billion litres from food grains, which will have a significant impact on the agriculture sector.

The following are the main amendments approved to the National Policy on Biofuels:

- To allow more feedstocks for production of biofuels,

- To advance the ethanol blending target of 20% blending of ethanol in petrol to 2025-26 from 2030,

- To promote the production of biofuels in the country, under the Make in India Program, by units located in Special Economic Zones (SEZ)/ Export Oriented Units (EoUs). This proposal will attract and foster developments of indigenous technologies which will pave the way for the 'Make in India' drive and thereby generate more employment,

- The amendments have also called for adding more members to the National Biofuel Coordination Committee (NBCC), which is chaired by the Union Minister of Petroleum And Natural Gas and has members from 14 other ministries.

- To grant permission for export of biofuels in specific cases, and

- To delete/amend certain phrases in the policy in line with decisions taken during the meetings of National Biofuel Coordination Committee.

Significance of the amendments

- The existing National Policy on Biofuels came up during the year 2018. This amendment proposal will pave the way for 'Make in India' drive thereby leading to reduction in import of petroleum products.

- Since many more feedstocks are being allowed for production of biofuels, this will promote the Atmanirbhar Bharat and give an impetus to Prime Minister's vision of India becoming 'energy independent' by 2047.

Key Challenges to the amendments

The GOI’s increased bio-fuel ambition demands a shift towards 1G production and edible feedstocks, with serious implications on lifecycle benefits.

The low yield for sugarcane and maize in India will require land-use change, significantly affecting embodied total GHG emissions.

Sugarcane

- Sugar-based ethanol production currently uses (almost exclusively) molasses, a by-product of the sugar-making process. A 2015 study by Soam et. al. found that lifecycle emissions for molasses-based ethanol were 8,736 kg CO2 eq./tonne of ethanol, compared to 512 kg CO2 eq./tonne of ethanol when energy-use was apportioned.

- NITI Aayog goal of producing 6.78 billion litres from sugarcane will require an additional 6.26 million hectares under sugarcane by 2025, which will thus have a significant negative impact on the lifecycle emissions from this feedstock.

- The other sugarcane pathway involves the use of sugarcane juice directly, possibly reducing the need for land-use change. However, sugarcane cultivation is water-intensive and depends heavily on consistent rainfall patterns. Indeed, the cultivation of sugarcane has led to severe water stress and drought-like conditions in some districts, affecting all forms of livelihood.

- Increased sugarcane cultivation will divert irrigation water away from critical food-grain crops. Furthermore, high fertiliser requirement for sugarcane cultivation also increases the environmental footprint of this pathway. Thus, meeting the ambitious ethanol goal from sugarcane is not necessarily environmentally sustainable from the perspective of the entire agricultural system.

Rice

- The process of using FCI-procured rice for ethanol is essentially uneconomical, since the economic cost of the stored paddy is usually much higher than the minimum support price at which it is procured, and includes incidental expenses such as transport, labour, taxes, freight, and handling.

Maize

- Searchinger et al. estimated that maize-based ethanol could nearly double GHG emissions over 30 years, compared to gasoline.

- Considering an ethanol yield of 380 litres/ tonne as suggested by the NITI Aayog, meeting the food-grain requirement for ethanol production from maize will require an additional 4.82 million ha. of land under maize cultivation—more than half of the present 9.42 ha. under maize cultivation.

- Thus, a maize-dependent pathway will require major land-use changes. The US experience has already shown that a low-yield maize pathway combined with land-use changes not only leads to minimal carbon emission benefits but can also increase maize prices, severely impacting the poultry and livestock industry.

Biodiesel

- The use of Jatropha for biodiesel production has largely been unsuccessful due to low yields. The expected yield was 2-5 mg/ha. per year, whereas the actual yield was closer to 0.5-1.5mg/ha. per year.

- Thus, the actual land required to produce a five percent blending rate is much higher than expected and farmers’ profits much lower. Further, Jatropha was found to increase weeding in many areas, ruining local habitats and leading to the loss of other ecosystem services.

Also,

- The agricultural sector receives subsidies for inputs and power, in addition to MSP, leading to unsustainable use of water and fertilisers.

- Land revival programmes are inhibited by the lack of a robust mechanism for the classification of wastelands and complicated land ownership patterns

- The use of competing agricultural feedstocks can create conflict between different agricultural lobbies. Just recently, sugarcane farmers wrote a letter to the prime minister, alleging that OMCs were increasingly favouring ethanol from maize, affecting their livelihoods.

- Promoting 1G biofuels will lead to technology lock-ins, delaying the switch to 2G feedstocks. Incentives for sugarcane- and maize-based production will be difficult to repeal once implemented, given the strength of agricultural lobbies in most states.

Policy Recommendations

- For a sustainable transition, the long-term biofuel pathway should be based on waste (2G) and algal biomass (3G). Such approaches will ensure reductions not only in oil imports but also in carbon emissions.

- Furthermore, a waste-based pathway will ensure higher levels of biofuel production, since a larger part of the biomass can be apportioned for fuel production, without posing a threat to food security and land.

- In the long run, waste-based biofuels will also be cheaper for consumers, since the raw materials are cheaper than edible feedstock.

- In India, the cost of ethanol is significantly higher than in other countries, due to government-regulated pricing of agricultural commodities. It can also be an effective solution to the problem of air pollution arising from the burning of agricultural wastes.

- Currently in India, Biofuel development is centred around the cultivation of Jatropha plant seeds. There is need to develop new feedstock for biofuels.

- To facilitate the blending of biofuels with conventional fuels, there is need to set up advanced biorefineries.

- Research and development should be promoted to support generation of bio-fuel from waste. As it will ensure realizing the goal of waste management and waste to energy.

- According to the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI), India produces around three million tonnes of used cooking oil (UCO), 60 percent of which goes back to the food chain, leading to adverse health impacts. Currently, the FSSAI does not have the resources required to enforce the established standards for the disposal of used cooking oil. Thus, larger agencies such as State Pollution Control Boards must be deployed, and the procurement of UCO for conversion to biodiesel strengthened. The government has announced a scheme for greater procurement of UCO. Going forward, such efforts need to be sustained and amplified.

- Faster uptake of 2 G fuels is hindered by the high costs of production and high risks, which throttle innovation. To tackle this issue, public enterprises should scale up investment in pilot projects for 2G biofuels. International grants and loans should be redirected towards 2G fuels, and existing frameworks (e.g., the Clean Development Mechanism) can be leveraged to direct funding to this sector. Innovation will also need to be encouraged through fiscal incentives, such as tax credits for the production of cellulosic biofuel and loan guarantees for pilot projects. Some of the measures have already been successfully applied in other countries.

Table 2: Snapshot of Lignocellulosic Biomass Options for Second-Generation Biofuels

|

Feedstock

|

Advantages

|

|

Availability

|

|

Dedicated Energy Crops

|

|

Short-rotation crops

|

Poplar,

willow

eucalyptus,

Locust.

|

Fast-growing, prevention of soil erosion, increased soil fertility in some cases.

|

|

Year-round

|

|

Perennial crops

|

Miscanthus switchgrass, reed canary grass, and other grasses

|

Useful for reviving degraded land, prevention of soil erosion, increased soil fertility in some cases.

|

|

Summer and Autumn

|

|

Primary Residues

|

|

Agriculture

|

Straw, stover

|

Cheap, promotes a circular economy, no land-use change, additional value creation for farmers, reduced pollution from waste burning

|

|

Only during crop harvesting season

|

|

Forestry residues

|

Treetops, branches, stumps

|

Cheap, no land-use change, prevents forest fires

|

|

Year-round

|

|

Secondary Residues

|

|

Crop processing

|

Coffee, rice, corn, cacao

|

No land-use change, concentrated at processing site, reduces disposal costs,

|

|

Year-round

|

|

Sugar ethanol production

|

Sweet sorghum, bagasse, pulp

|

|

Only harvesting season

|

|

Forestry processing

|

Sawdust, bark

|

|

Year-round

|

|

Tertiary Residues

|

|

Municipal solid waste

|

Palettes, furniture, timber

|

Concentrated at landfill sites, reduces disposal costs, no additional land

|

|

Year-round

|

Conclusion

- The key tenets of India’s Biofuel Policy are unique and forward-looking, with a clear focus on 2G feedstocks and land regeneration. However, in its desire to accelerate biofuel blending targets, the administration has redoubled its focus on food-grain based feedstock. Such a pivot has significant negative implications in terms of lifecycle GHG emissions, water stress, ethanol pricing, and distortions to the agricultural supply chain—exacerbating unsustainable land-use practices without guaranteeing emissions reduction.

- The GOI needs to refocus on 2G production and 3 G production methods, based on a clear roadmap and backed by policy and financial support.

- While this can delay biofuel blending targets by some years, it will not only ensure a sustainable reduction in GHG emissions but also provide multiple economic and environmental co-benefits. A long-term, sustainable approach to biofuel production can help India become a champion for sustainable transport biofuels.

https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1826265