India replaced its sedition law (Section 124A of the IPC) with Section 152 of the BNS, sparking criticism for its potential threat to free speech due to broad wording, leading to the Supreme Court's review to balance national security with the fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: NEWSCLICK

India has replaced sedition law, Section 124A of the IPC, with Section 152 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), but critics argue the new law's broad wording continues to threaten free speech and dissent against government actions.

Sedition refers to an act or speech that provokes or attempts to provoke hatred, contempt, or disaffection towards the government established by law.

1870 – British enactment: Colonial government inserted IPC 124A in 1870 to suppress Indian nationalists. It was used against freedom fighters (Tilak, Gandhi, Bhagat Singh, etc.).

1942–1947 – Judicial interpretation: In Niharendu Dutt Majumdar vs King Emperor (1942), the Federal Court limited sedition to speech inciting public disorder. But in King Emperor vs Bhalerao (1947) the Privy Council rejected that limit.

Post-Independence changes: Constituent Assembly (1949) dropped sedition from the Constitution. However, the First Amendment (1951) allowed “public order” as a free-speech restriction.

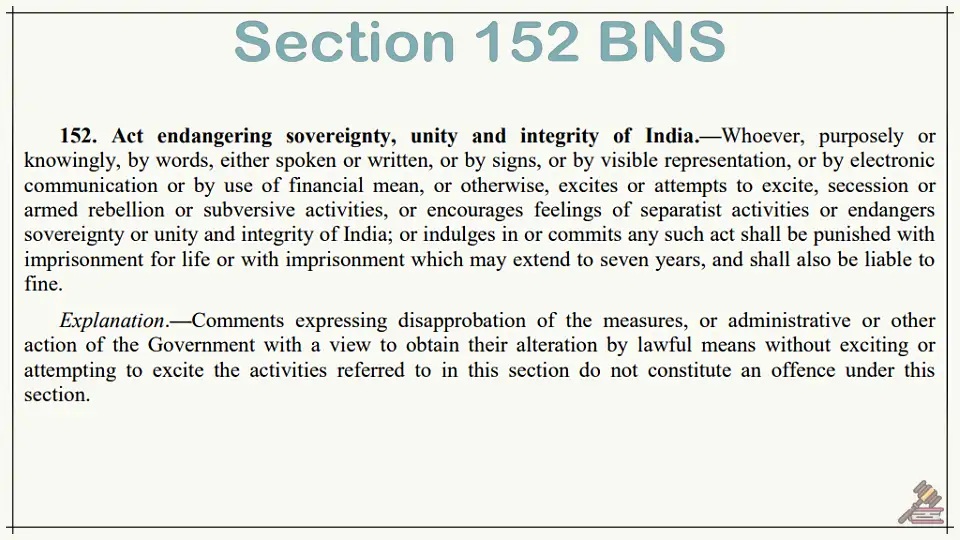

Section 124A IPC punishes anyone who, by words or signs, brings “hatred, contempt or disaffection” against the government established by law in India.

Supreme Court limits (Kedar Nath Singh, 1962): The SC upheld 124A as constitutional under Art. 19(1)(a)/(2), but narrowed it.

D.K. Basu vs State of West Bengal (1997): Supreme Court mandated that police officers making an arrest must wear proper identification, prepare a memo of arrest, inform the arrestee's family or friends, and allow the arrestee to consult a lawyer.

S.G. Vombatkere vs Union of India (2022): Supreme Court, acknowledged concerns about misuse and the colonial legacy of Section 124A, ordered its suspension, effectively barring new prosecutions and staying pending cases.

Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita 2024: Replaced the IPC.

In August 2025, the Supreme Court to examine the constitutionality of Section 152 of the BNS.

In August 2025, the Supreme Court to examine the constitutionality of Section 152 of the BNS.

Vagueness and Expansive Interpretation: Section 152 criminalizes "acts endangering the sovereignty, unity, and integrity of India" without clearly defining.

Lower threshold for offence: Section 152 includes the term "knowingly," which critics argue lowers the threshold for prosecution compared to the IPC's requirement of intent to provoke disaffection.

Negative Effect on freedom of expression: Section 152 is a cognizable and non-bailable offense, allowing arrests without warrant and leading to prolonged detention and harassment even without sufficient evidence.

Scope of misuse and absence of safeguards: NCRB data shows that between 2015 and 2020, out of 548 persons arrested under Section 124A, only 12 faced conviction.

Heightened digital surveillance concerns: Section 152 includes acts committed through "electronic communication" and "financial means" within its scope.

Judiciary's role and potential for unconstitutionality: Supreme Court is reviewing the constitutionality of Section 152, faces the challenge of balancing the state's interest in protecting national security with the fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression.

Shift in Focus: IPC Section 124A targeted acts against the "Government established by law in India," while BNS Section 152 shifts the focus to "actions endangering the sovereignty, unity, and integrity of India", protect democratic interests of Independent India.

Protection of Legitimate Dissent: Law does not punish criticism of government policies and actions, thereby upholding the democratic right to dissent.

Higher Threshold of Applicability: Inclusion of the term "purposely or knowingly" in Section 152 signifies a higher threshold for prosecution compared to the old law.

Modernization of Law: Replacing colonial-era laws with new legislation reflecting contemporary societal concerns, including cybercrimes and digital fraud.

Protection against Real Threats: Government views Section 152 as a crucial tool to protect national security and combat serious threats, such as secession, armed rebellion, subversive activities, and separatism.

Redefinition vs Repeal: Some Legal experts have advocated for repealing sedition laws, labeling them colonial origin unsuitable for a modern democracy, quoting instances where laws have been used against journalists, activists, and dissidents.

Learn from international best practices: Other democracies have largely abandoned sedition laws, opting to address genuine threats through specific crimes like treason, terrorism, or hate speech. The United Kingdom repealed sedition laws in 2009.

Procedural safeguards: Law Commission of India in its 279th Report has recommended procedural safeguards, such as requiring a preliminary inquiry by a police officer (not below the rank of inspector) before filing an FIR under sedition provisions, to prevent frivolous or politically motivated charges.

Training and sensitization: Training programs for police officers and magistrates to ensure that they understand the constitutional limits of sedition laws and adhere to Supreme Court precedents.

Ensuring accountability: Implementing penalties for law enforcement officials who file baseless/politically motivated charges under sedition provisions is necessary to deter misuse and ensure accountability.

Enhanced transparency and data collection: Government should publish regular reports on the number of cases filed, arrests made, and convictions secured, for better monitoring of the law's application and potential misuse.

Prioritizing constitutional principles: All legislative and judicial measures must adhere to the spirit of the Constitution, particularly Articles 14 (right to equality), 19(1)(a) (freedom of speech and expression), and 21 (right to life and personal liberty).

The issue surrounding sedition laws, evolving from the colonial-era Section 124A of the IPC to the BNS's Section 152, presents an ongoing challenge of balancing national security with safeguarding free speech and dissent, which demand careful legislative and judicial consideration to ensure democratic values are upheld.

Source: THE HINDU

|

PRACTICE QUESTION Q. Sedition law is a colonial relic and its continued existence is a blot on India's democratic credentials. Critically analyze. 250 words |

It is a law that punishes any act, whether through words or signs, that attempts to bring hatred or contempt against the government.

No, sedition is a non-bailable offense, which means a person can be arrested without a warrant and can't get bail as a matter of right.

The punishment can range from imprisonment up to three years, to a life term, along with a fine.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved