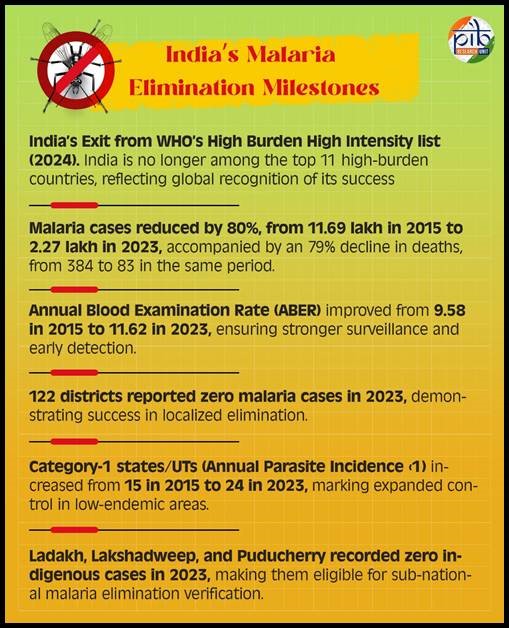

India has made major progress toward malaria elimination under its National Framework for Malaria Elimination (2016–2030), with cases falling by around 80% between 2015 and 2023. Many districts have already reported zero indigenous cases, and the country has exited the WHO High Burden to High Impact group. The strategy now focuses on strong surveillance through the “Test, Treat and Track” approach, universal access to diagnosis and treatment, and intensified vector control.

However, challenges remain in the form of migration, urban malaria, hard-to-reach tribal and forested areas, and the persistence of Plasmodium vivax, which can relapse. Drug and insecticide resistance are also emerging concerns. India aims to achieve zero indigenous cases by 2027 and full elimination by 2030, but success will depend on accurate reporting, strong urban and community participation, and preventing re-establishment of transmission in malaria-free areas.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: The Hindu

India is on track to eliminate malaria by 2030, but achieving this requires sustained efforts across surveillance, treatment, prevention and addressing challenges like migration, urban malaria and drug resistance.

|

Must Read: Malaria | WORLD MALARIA REPORT | WORLD MALARIA DAY | MALARIA VACCINE | |

Current status of Malaria in India

|

World Malaria Report 2025 (WHO) It highlights continued progress globally, with billions of cases and millions of deaths averted since 2000. India remains a major contributor to cases in the WHO South-East Asia Region (over 70 %), underlining both progress and the scale of the challenge. The report reiterates that sustained surveillance, diagnostic capacity and targeted regional coordination remain crucial. It also flags antimalarial drug resistance threats, which need monitoring and adaptation of treatment protocols. |

Source: PIB

What is Malaria and how does it spread?

Malaria is a serious infectious disease caused by Plasmodium parasites. People become infected when they are bitten by an infected female Anopheles mosquito, which transmits the parasite into the bloodstream. The disease is most common in warm, tropical climates.

Malaria does not usually spread directly from one person to another, but transmission can rarely occur through blood transfusions, shared needles, or from mother to child during pregnancy. If prompt treatment is not given — especially in infections caused by Plasmodium falciparum — the illness can quickly become severe and may turn fatal within a short time.

Symptoms:

Early signs of malaria often resemble flu-like illness. The most frequent symptoms are:

These symptoms typically appear about 10 to 15 days after an infective mosquito bite. In people who have had malaria before, symptoms may be milder, which can delay diagnosis.

In more serious cases, malaria can progress to severe disease, leading to:

Certain forms of malaria are particularly dangerous and can be life-threatening if not treated quickly.

Prevention:

Prevention mainly focuses on protecting against mosquito bites and, when necessary, using preventive medication.

Key challenges in malaria elimination:

Persistent high-transmission pockets: Even though India reduced malaria cases by about 80.5% between 2015 and 2023, transmission remains concentrated in certain tribal, forested and hard-to-reach districts, making consistent intervention difficult.

Migration: Movement of people from high-burden areas continues to pose a threat of reintroducing malaria to places that have achieved low transmission, undermining elimination gains.

Urban Malaria spread: The spread of invasive vectors like Anopheles stephensi in urban settings has increased malaria risk in cities, where dense populations and infrastructure challenges complicate control.

Species complexity and relapse: Plasmodium vivax, which makes up a large share of India’s malaria cases, can lie dormant and cause relapses, hindering complete interruption of transmission.

Surveillance and reporting gaps: Timely and complete case reporting remains uneven, especially from private health providers and peripheral areas, limiting accurate tracking of residual transmission.

Resistance to insecticides and drugs: Emerging resistance among mosquito vectors to insecticides and among parasites to antimalarial drugs threatens the effectiveness of current prevention and treatment strategies.

Government initiatives on Malaria elimination:

|

Initiative |

Description |

|

National Framework for Malaria Elimination (NFME) 2016–2030 |

A strategic roadmap launched to eliminate malaria (zero indigenous cases) by 2030, with phased targets (interruption by 2027), developed through national consultation under the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. |

|

National Strategic Plan (NSP) for Malaria Elimination 2023–27 |

Builds on the NFME to accelerate elimination, emphasising real-time, case-based surveillance and the “Test, Treat, Track” approach to detect every infection, initiate prompt treatment, and interrupt transmission. |

|

National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme (NVBDCP) |

The nodal programme under the Government of India coordinating malaria control and elimination efforts alongside other vector-borne diseases, with objectives including reducing morbidity & mortality and interrupting transmission. |

|

High Burden to High Impact (HBHI) Strategy Implementation |

In collaboration with WHO, high-endemic states were targeted with intensified interventions to reduce malaria burden, contributing to India exiting the HBHI group in 2024. |

|

Integrated Health Information Platform (IHIP) Data System |

Enables real-time tracking of cases and enhances surveillance quality, helping policymakers tailor responses based on live data. |

|

State-Level Elimination Drives |

States like Uttar Pradesh are running intensified elimination campaigns with deep case investigations, community education, and vector control measures to achieve zero indigenous cases by set targets. |

|

Targeted High-Burden District Programmes (e.g., IMEP-3) |

Special efforts in priority districts include enhanced surveillance, treatment access, vector control, and community mobilisation under intensified elimination projects. |

|

Alignment with WHO & Global Goals |

India’s national plans align with the WHO Global Technical Strategy for Malaria 2016–2030 and aim to meet global milestones such as substantial incidence reduction and certification pathways. |

Way Forward:

Conclusion:

India has made remarkable progress in reducing malaria and is moving steadily toward elimination, but the final phase demands vigilant surveillance, targeted action in high-risk areas, and sustained political and community commitment. Preventing re-establishment of transmission will be just as important as eliminating the remaining cases to achieve a malaria-free India by 2030.

Source: The Hindu

|

Practice Question Q. “India has moved from malaria control to malaria elimination, but the last mile is the toughest.” |

India has set two milestones: achieving zero indigenous cases by 2027 and complete malaria elimination by 2030. This aligns with the World Health Organization’s Global Technical Strategy for Malaria and is being implemented through the National Framework for Malaria Elimination (2016–2030) and the National Strategic Plan for Malaria Elimination (2023–27).

Malaria elimination means that no malaria cases are transmitted locally within India. Imported cases from other countries may still occur, but no onward local transmission happens. It is different from eradication, which means the disease disappears globally.

India has shown remarkable progress over the last decade. Total cases and deaths have dropped significantly, and malaria is now largely confined to specific pockets instead of being widespread. However, tribal and border regions still report higher transmission.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved