The Telangana dispute over Lambadas’ ST status pits indigenous tribes against a community granted recognition in 1976. Adivasi groups allege benefit monopolization, while Lambadas cite historic marginalization. Now before the Supreme Court, the issue exposes tensions around identity, reservation equity, politics, and ST identification under Article 342.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: DOWNTOEARTH

Context

The decades-old dispute over granting Scheduled Tribe (ST) status to the Lambada (Sugali/Banjara) community in Telangana has been reignited and is now before the Supreme Court.

|

Read all about: ST Status in India: Process & Criteria l Criteria To Define STs |

What is Adivasi-Lambada Conflict?

It is an ongoing socio-political dispute in Telangana between aboriginal tribal communities (Adivasis) and the Lambada (Banjara) community.

The core of the tension is the Adivasis' demand for the exclusion of Lambadas from the Scheduled Tribes (ST) list.

Core of the Conflict

ST Status Dispute

Adivasis (Gonds, Kolams, Pardhans, etc.) allege that Lambadas, a nomadic group from Rajasthan, were "unfairly" added to the ST list via an unconstitutional ordinance in 1976 during the Emergency.

Resource and Opportunity "Cornering"

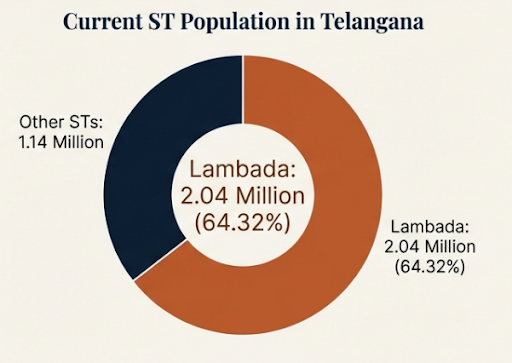

Adivasis allege that Lambadas, who are more educationally advanced and populous, have disproportionately occupied government jobs and educational seats meant for STs.

Land Alienation

There are frequent clashes over land. Adivasis accuse Lambadas of encroaching on their ancestral lands in "agency" (tribal) areas, sometimes aided by controversial administrative circulars.

Cultural Differences

Cultural symbols cause tension; in 2017, Adivasis vandalized a Lambada statue at the Kumram Bheem Tribal Museum, alleging Lambadas excluded themselves from historical tribal uprisings.

Arguments of Both Communities

|

Argument Point |

Adivasi Groups' Position |

Lambada Community's Position |

|

Indigeneity |

Lambadas, who migrated from Rajasthan centuries ago, are not indigenous to Telangana and lack the cultural and historical traits of the region's aboriginal tribes. |

They have a distinct nomadic culture, language, and history of marginalization that justifies their tribal status. |

|

1976 Inclusion |

The inclusion was a political decision made without proper anthropological verification and has disrupted the social fabric of tribal areas. |

The amendment corrected a historical oversight by removing regional restrictions and recognizing their tribal identity statewide. |

|

Socio-Economic Status |

Lambadas' socio-economic and educational advancement enables them to unfairly monopolize ST reservation benefits. |

Historically disadvantaged, the community still needs affirmative action for upliftment. |

Constitutional and Legal Framework For ST Status

Key Constitutional Provisions

Article 366(25): Defines Scheduled Tribes as communities deemed as such under Article 342.

Article 342(1): Empowers the President of India, after consulting the Governor of a state, to specify the tribes or tribal communities to be considered STs in that state or Union Territory via a public notification.

Article 342(2): Grants the Parliament the exclusive power to include or exclude any community from the ST list through a law. Any modification to the initial presidential notification requires a Parliamentary Act.

Criteria for ST Identification (Lokur Committee, 1965)

The Constitution does not define the criteria for ST status, the Lokur Committee laid down five benchmarks for identification:

Adivasi groups argue that the Lambada community does not fulfill several of these criteria in the context of Telangana.

Procedure for Inclusion in the ST List

What are the reasons for Increasing Demand for ST Status?

Socio-Economic Benefits

Access to reservations in educational institutions (Article 15(4)) and government jobs (Article 16(4)). Eligibility for numerous welfare schemes and funds under the Tribal Sub-Plan (TSP).

Political Representation

Reservation of seats in the Lok Sabha and State Legislative Assemblies (under Article 330 and 332), ensuring political voice and representation.

Protection of Land & Culture

Special legal protections against land alienation and for self-governance under laws like the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act (PESA), 1996, and the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 (FRA).

Challenges of the Identification Process

Outdated and Subjective Criteria

The criteria from the 1965 Lokur Committee—specifically "primitive traits" and "shyness"—used for tribal classification are considered outdated and difficult to apply objectively in modern India.

Political Influence

The inclusion process is often driven by political calculations and vote-bank politics rather than genuine socio-economic need, undermining its integrity.

Dilution of Benefits

The inclusion of more populous and relatively advanced communities can lead to them capturing a disproportionate share of reservation benefits, disadvantaged the most vulnerable tribal groups.

Fueling Inter-Community Conflict: It creates resentment and conflict between existing STs and newly included groups over resources, jobs, and political power.

|

Judicial Intervention The Supreme Court ruling in State of Punjab vs Davinder Singh (2024) case affirmed the states' power to create sub-classifications within the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes lists. This allows for "quotas-within-quotas" to ensure reservation benefits fairly reach the most disadvantaged communities within the ST list. |

Way Forward

Modernize the Criteria

An expert committee should be formed to replace the Lokur Committee's criteria with new, objective socio-economic guidelines (e.g., poverty, health, education), abandoning colonial "primitiveness" standards.

Ensure Data-Driven Transparency

Inclusion must use rigorous, independent, and public data. Prior mandatory consultation with existing ST Gram Sabhas (under the PESA Act) is required before adding any community to a state's list.

Strengthen Institutional Roles

The National Commission for Scheduled Tribes (NCST) and the Registrar General of India (RGI) must be empowered with greater autonomy and resources to conduct unbiased and thorough assessments, free from political pressure.

Focus on Effective Implementation

Prioritize fully implementing the PESA Act of 1996 and the Forest Rights Act of 2006 to secure tribal rights over land, resources, and self-governance, directly tackling the root causes of marginalization.

Conclusion

Reforming the Scheduled Tribes identification process with a modern, data-driven framework is essential for social justice, national integrity, and empowering tribal communities by ensuring constitutional safeguards reach the marginalized.

Source: DOWNTOEARTH

|

PRACTICE QUESTION Q. The inclusion of new communities into the Scheduled Tribes list often leads to conflicts over the distribution of affirmative action benefits. 150 words |

The core issue is the inclusion of the Lambada (Banjara) community in the Scheduled Tribes (ST) list in 1976. Adivasi groups claim that Lambadas are not indigenous to the region and, being more populous and advanced, have cornered a disproportionate share of reservation benefits in jobs and education meant for vulnerable tribes.

The Lambadas were included in the ST list for the Telangana region through the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Orders (Amendment) Act, 1976, passed by the Indian Parliament.

Article 342 of the Constitution empowers the President, in consultation with the Governor, to specify the tribes to be deemed as STs. However, only the Parliament has the authority to include or exclude any community from this list through a subsequent law.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved