In international relations and geopolitics, there are no friends or enemies, only permanent interests. The year, 2020 marked the 70th anniversary of the establishment in diplomatic ties between India and China. But ironically the two countries have been engaged in holding disengagement talks since a few months now. Relations between contemporary China and India have been characterized by border disputes, resulting in several military conflicts.

But the question is, “Are we sharing a bitter relationship since the very beginning”?

To understand the current nature of the situation, we must travel back in time and try to analyze the evolution of relations between the two countries.

OVERVIEW

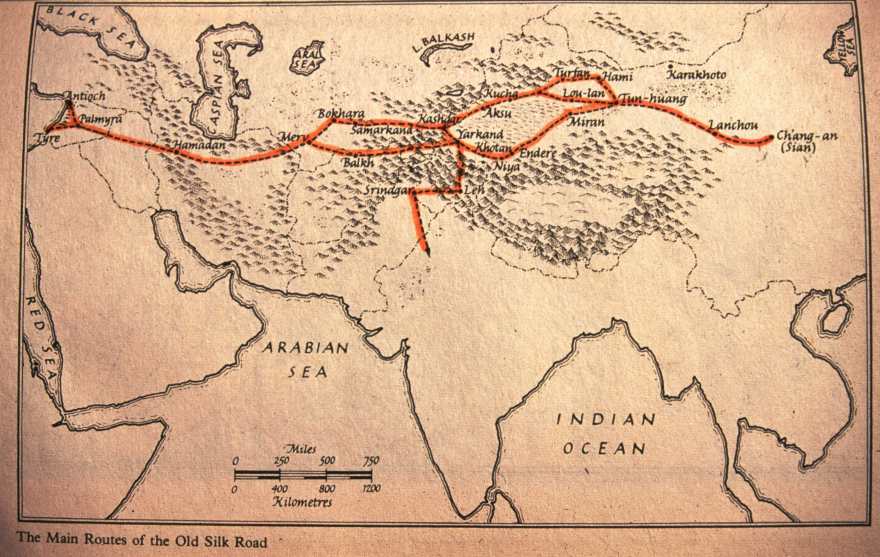

India-China-relations dates back to more than 2,000 years ago. There have been cultural and economic ties between the two countries since ancient times. The Silk Road not only served as a major trade route between India and China, but is also credited for facilitating the spread of Buddhism from India to East Asia.

India-China relationship was limited to pilgrimage and a little bit of trade till pre-1950s. However, a new chapter heralded after India got Independence in 1947 and the Communist Revolution took place in China in 1949.

|

The Chinese Communist Revolution, known in mainland China as the War of Liberation, was the conflict, led by the Communist Party of China and Chairman Mao Zedong. It resulted in the proclamation of the People's Republic of China, on 1 October 1949. It was the second part of the Chinese Civil War (1945–49). Historians have traced the origins of the 1949 Revolution to sharp inequalities in society. |

The modern relationship was setting in motion in the 1950s when India became one of the first countries to end formal ties with the Republic of China (Taiwan) and recognize the People's Republic of China (PRC) as the legitimate government of mainland China.

Also, Tibet had acted as a buffer between India and China for thousands of years. It is only after the 1950s that the two countries are sharing a common border after China invaded and occupied Tibet.

If we step back a little bit in time we can recollect how, India and China played a crucial role during the World War II by halting the progress of Imperial Japan.

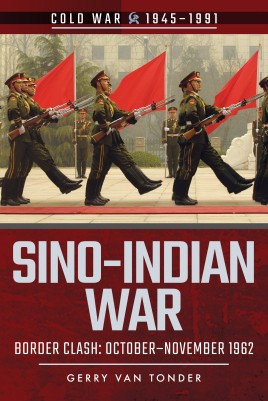

However, relations between contemporary China and India have been characterized by border disputes, resulting in military conflicts like — the Sino-Indian War of 1962, the Chola incident in 1967, the 1987 Sino-Indian and the 2020 India-China skirmish.

Since the late 1980s, both countries successfully rebuilt diplomatic and economic ties. In 2008, China became India's largest trading partner and the two countries extended their strategic and military relations to some extent.

Today, China and India are the two most populous countries and fastest growing major economies in the world. Growth in diplomatic and economic influence has increased the significance of their bilateral relationship.

Despite this, the relations between India and China have come under “severe stress” time and again in the last decade due to multiple border stand-offs along the Line of Actual Control.

“The Chinese Government has tried to delude us by professions of peaceful intentions.”

-Sardar Vallabhai Patel, 1950

THE ANNEXATION OF TIBET AND THE PANCHSHEEL AGREEMENT

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) under the Communist Party had established diplomatic relations with the Indian Government in 1950. Despite this, they saw India’s concern over Tibet as interference in their internal affairs.

Eventually, they decided to re-assert control over Tibet by force. This finally ended in Tibet conceding suzerainty to China. This would later form the basis on which China would attempt to claim Arunachal Pradesh as Southern Tibet.

It was in 1954 that India and China signed the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, known as the Panchsheel Agreement - a treaty signed between Jawaharlal Nehru and Premier Zhou Enlai to bring peace to the post-colonial sub-continent.

The principles were emphasized by the Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, in a broadcast speech made at the time of the Asian Prime Ministers Conference at Colombo just a few days after the signing of the Sino- Indian treaty in Beijing.

Five principles of Panchsheel Agreement:

On signing this treaty, India and China had an agreement of peace and non-interference. Effectively, this meant that India formally recognized China’s control over Tibet.

It was at this juncture that the deterioration in diplomatic ties began.

The Chinese began constructing a highway through the Tibet side of the borders. They went on to construct it through parts of today’s Aksai Chin that was actually a part of India. India came to know of the road only through China’s announcement in 1957, a month before the road was to be opened, and thus tensions between the countries rose.

|

In a letter dated 5th February 1960, Nehru wrote to Zhou, “In the latest note from the Government of the People’s Republic of China, emphasis has been laid on our entire boundary never having been delimited. That is a statement which appears to us to be wholly incorrect, and we cannot accept it. On that basis there can be no negotiations.” |

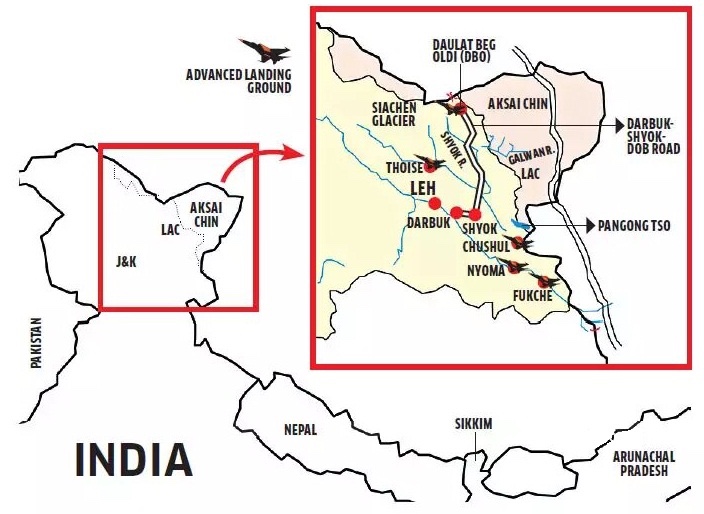

Map: China’s occupation of Aksai Chin since 1950s

By now, China even stopped pretending all friendship with India. Despite that, in the 1950s, the then Indian Prime Minister Nehru declined an informal US offer to have a permanent seat in the UNSC, and said that China be given it instead. It is said he believed that since India was ‘non-aligned’, they would not require it. Experts believe that our political strategies and leadership before the war were idealistic in nature.

However, in 1961, the Indian Government under Nehru identified a set of tactical strategies designed with the ultimate goal of effectively forcing the Chinese from India’s territories. Then the Forward Policy was introduced.

THE FORWARD POLICY

A forward policy of a country is a set of foreign policies applicable to territorial disputes where the emphasis is on securing control over targeted territories.

Around mid-June of 1962, at the disputed areas, 12–15 Indian soldiers were sent without any logistical supply or reinforcement. This instigated China, and they attacked India on the grounds of Chinese sovereignty and integrity. Control of the Aksai Chin area became difficult for both the sides due to different ideas of international borders. There were many instances of patrolling parties of both sides clashing against each other, which a lot of times took a violent turn.

All these issues slowly led to a war between India and China.

Before we discuss about the Sino-Indian War, let us understand what is the root source of Border-Tensions between the two countries..

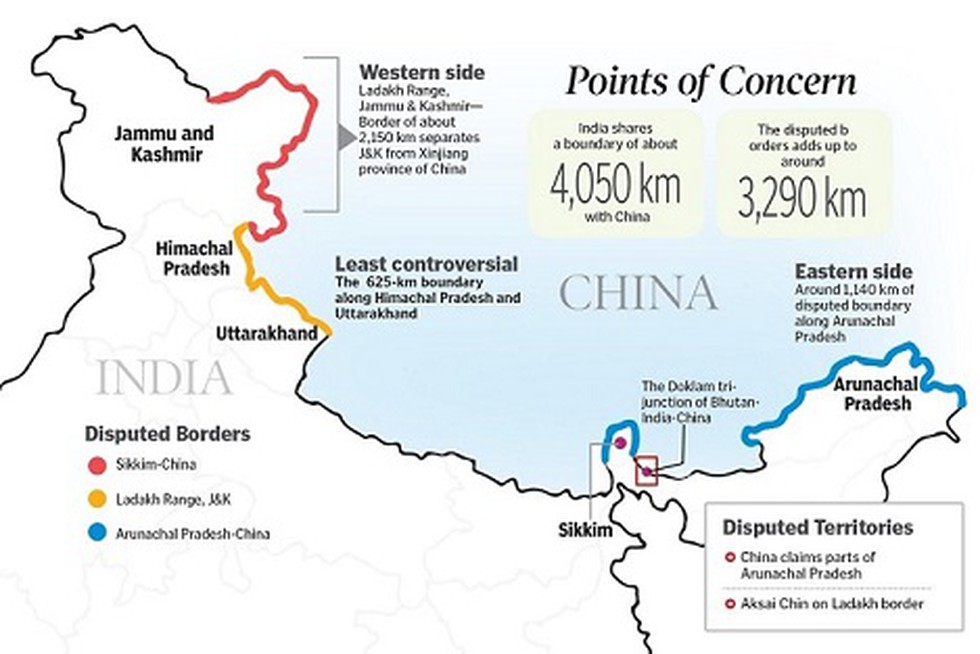

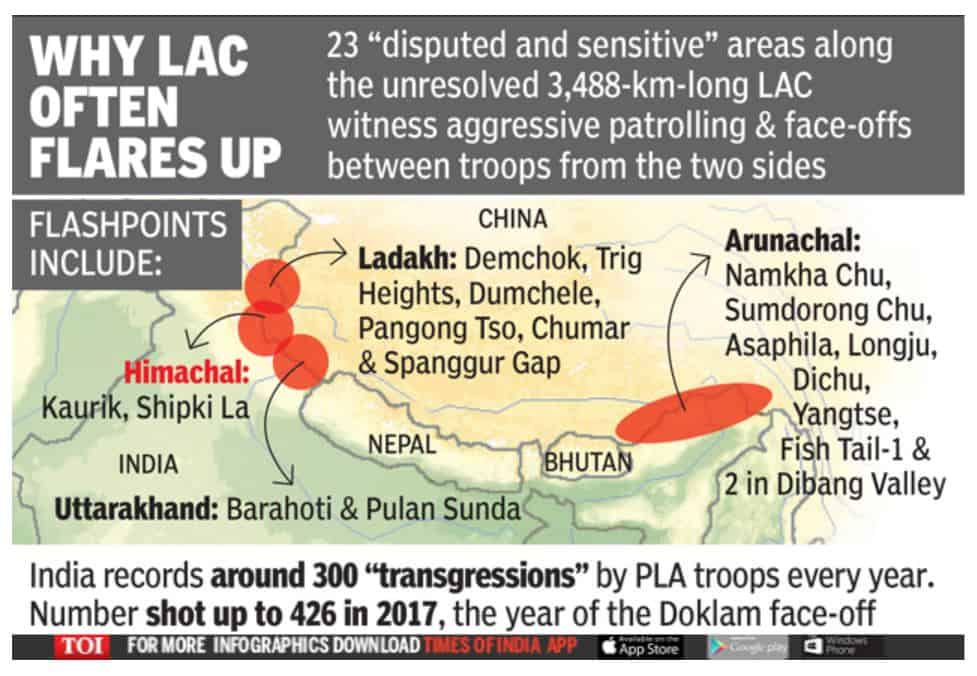

The root cause lies in an ill-defined, 3,440km (2,100-mile)-long border that both countries dispute.Four states - Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand (erstwhile part of UP), Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh and Union Territories of Ladakh (erstwhile state of Jammu & Kashmir) share a border with China.

The Sino-Indian border is generally divided into three sectors namely: Western sector, Middle sector, and Eastern sector.

Western Sector

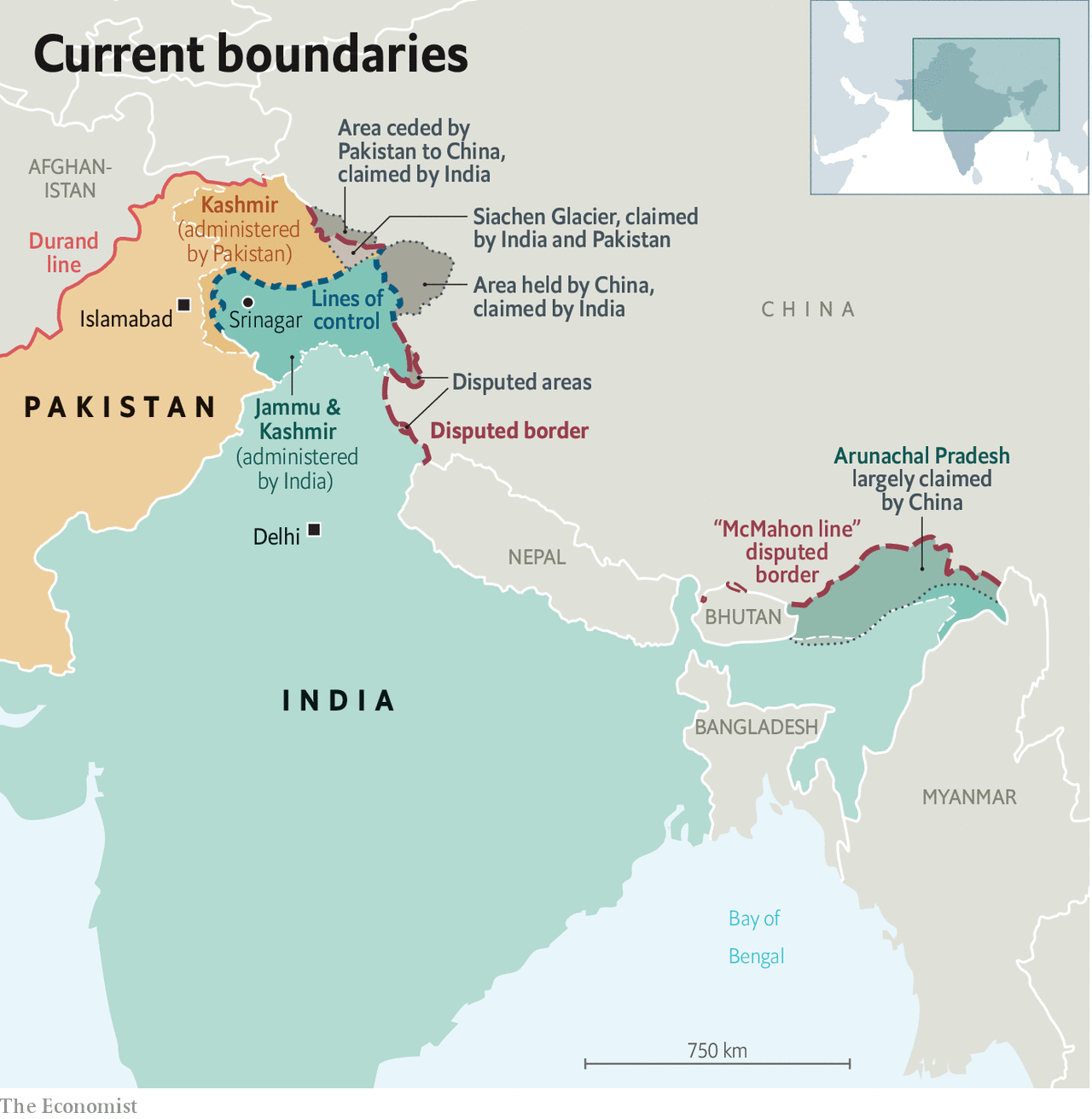

In the western sector, India shares about a 2152 km border with China. It is between the union territory of Ladakh (erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir) and the Xinjiang province of China. The territorial dispute in the western sector is over Aksai Chin. India claims it as part of erstwhile Kashmir, while China claims it is part of Xinjiang.

The dispute is said to be due to the failure of the British empire as it failed to demarcate a legal border between both countries. During the British rule in India two borderlines were proposed – Johnson’s line and McDonald line in 1865 and 1893 respectively.

The Johnson’s line shows Aksai Chin in Ladakh i.e. under India’s control whereas McDonald Line places it under China’s control. India considers Johnson Line as a rightful national border with China, while on the other hand, China considers the McDonald Line as the correct border with India. The different claims and perceptions of LAC have led to an overlapping area, within that area lies a small zone which both the sides patrol causing clashes of the Indian and the Chinese army.

At present, Line of Actual Control (LAC) is the line separating Indian areas of Ladakh from Aksai Chin. It is concurrent with the Chinese Aksai Chin claim line.

Middle Sector

In the middle sector, India shares about 625km of the border with China. This is the only sector where the both countries have less disagreement. The border runs from Ladakh to Nepal. The states of Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand touch the border with Tibet in this sector.

Eastern Sector

In the eastern sector, India shares a 1140km boundary with China. The boundary line is called McMahon Line runs from the eastern limit of Bhutan to a point near the Talu Pass at the trijunction of Tibet, India, and Myanmar. The majority of the territory of Arunachal Pradesh is claimed by China as a part of Southern Tibet.

China considers the McMahon line illegal. McMahon proposed the line in the Simla Accord in 1914 to settle the boundary between Tibet and India, and Tibet and China. Though the Chinese representatives at the meeting initialed the agreement, they subsequently refused to accept it.

China claims about 90,000 sq km of India’s territory in the northeast, including Arunachal, while India says 38,000 sq km of land in China-occupied Aksai Chin should be a part of Ladakh. There are several disputed areas along the Line of Actual Control (LAC), including in Himachal, Uttarakhand and Sikkim.

.jpg)

In Ladakh, the disputed areas include:

.jpg)

In Himachal Pradesh , the disputed areas are

.jpg)

In Uttarakhand, the disputed areas are-

.jpg)

In Sikkim, the disputed areas include:

.jpg)

Disputed areas in Arunachal Pradesh include:

On October 20, 1962, China’s People Liberation Army (PLA) invaded Ladakh and the McMahon Line.

China overran the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) and captured Tawang in only four days while making 3000 PoW (prisoner of war) camps.

The Indian army was significantly outnumbered on the forward posts. The war ended with China declaring a ceasefire and withdrawing its troops behind the ‘Line of Actual Control’, or the LAC.

The war taught us a lot of things, most importantly the necessity of military preparedness. The Army did an excellent job for the security of the nation, but the Government lacked political strategy and war preparation.

It was a massive humiliation to the country that the Chinese managed to enter our area and declared a ceasefire at the point till where their claim lied. According to China’s official military history, the war achieved China’s policy objectives of securing borders in its western sector.

The war also helped us see the Salami Slicing techniques used by China.

|

What is Salami Slicing? In the context of China, salami slicing denotes its strategy of territorial expansion in the South China Sea and the Himalayan regions. It is the process of making many small changes along the border which finally amass into a big change. Salami slicing means small, stealth military operations against neighbouring countries which accumulate over time in a large territorial gain. Such military operations are too small to lead to a war but significant enough to stump the neighbour who is not sure how and how much it should respond. A series of such actions not only accumulate territory for China but also become too frequent to attract international diplomatic attention. China's development of border areas helps it keep pushing into Indian Territory where infrastructure is poor which becomes a handicap for Indian forces. China's salami slicing works due to lack of even basic roads in large parts of border areas in India. China has assiduously built an extensive network of railway lines, highways, metal-top roads, air bases, radars, logistics hubs and other infrastructure in the entire Tibet Autonomous Region. China is the only country which has been expanding its territorial jurisdiction post-World War II at the expense of its neighbours. This expansion has taken place in both territorial and maritime regions. Acquisition of Tibet, capture of Aksai Chin and annexation of Paracel Islands are some of the glaring example of Chinese expansionist policy using this Salami Slicing Technique. |

The 1962 War left the border open for China to continue its creeping attempt to change the facts on military ground.

However, since 1962 here have also been many instances when China had to face setbacks after initiating aggression against India. Here's looking back at a few of them…

The Nathu La conflict is better known as the India-China war of 1967. In a strong message to China that the mistakes of 1962 won't be repeated, India landed a stern blow on the PLA's pride at the Nathu La post in Sikkim. In August 1967, Chinese troops infiltrated the Nathu La region. After observing that some Chinese troops were inside Sikkim, the Indian troops asked the Chinese commander to withdraw them from the Indian territory.

Repeated infiltrations kept happening despite the verbal warnings, which later turned into a scuffle between two sides.

On 6th September the Chinese went back to their own territory. After that, the Indian Army decided to de-escalate the tension. They laid a wire at the perceived border. Clashes reportedly erupted again between India-China when PLA launched an attack on Indian post at Nathu La where the wire was being laid.

In retaliation, Indian troops opened fire from the artillery observation posts which destroyed the Chinese bunkers. The conflict lasted till 15 September 1967 and resulted in a major setback for China with the loss of 400 soldiers.

Chinese troops intruded into Cho La sector on October 1, 1967, claimed the region and raised questions on Indian Army's position there. Cho La Pass connects the Indian state of Sikkim with China's Tibet Autonomous Region. Arguments soon turned into a fight, and although China eventually lost, the lives of 88 Indian Army personnel were lost and 163 were wounded, according to Defence ministry data.

20 years after Nathu La and Cho La, China again raised the issue of border disputes when India granted statehood to Arunachal Pradesh in 1986. This led to heated protests from the Chinese. In 1986, the Chinese army reportedly crossed LAC and entered the Sumdorong Chu valley in Arunachal Pradesh and started building helipads and permanent structures. Later, the Indian Army launched Operation Falcon. The Indian army stood at the border eyeball-to-eyeball with Chinese troops until the PLA agreed to back off.

Sumdorong Chu standoff (1987) in Arunachal Pradesh is said to be one of those incidents when India and China were on the verge of war.

After this, the first formal meeting to discuss "the freezing of the situation" since 1962 was held. At the meeting, both sides agreed to discuss the matter on the table. It would eventually lead to the pact of 1993, where the two countries agreed to ensure peace along the LAC.

The Government of India accepted the Chinese definition of the LAC by the agreements signed by the two sides in 1993 and 1996. These agreements laid down the precise locations of the LAC in the entire sector- Western, Eastern & Middle.

According to these agreements, both sides cannot hold military exercises above 15,000 troops. They need to limit the combat tanks, infantry combat vehicles, guns and any other weapon system mutually agreed upon. The two sides also need to exchange data on the military forces and arms to be reduced or limited.

They need to decide on ceilings on military forces and arms to be kept by each side within mutually agreed geographical zones along the LAC in the India-China border areas.

The 1993 and 1996 agreements have been broken by the PLA many times in the past. In the last decades, many incidents occurred in three different sectors Depsang(2013), Chumar(2014) and Doklam(2017) and now the Galwan Valley Incident (2020)

It started in the Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO) which is claimed by both sides. As a part of confidence-building measures (CBMs), both the Indian Army and the PLA had no permanent camps in the area.

But, on April 15 2013, the PLA set up a few permanent camps in Rakhi Nula which were immediately spotted by the Indian Army.

Negotiations between the two sides lasted for three weeks. Finally PLA took their bases back and India agreed to demolish some structures on the Indian side. No military aggression occurred throughout the entire incident.

Reason: Chinese construction of a highway that crossed to the Indian Territory. This standoff lasted for roughly two weeks.

The entire activity cooled down when the Chinese Government agreed to stop the highway construction.

On the other hand, the Indian Army agreed to destroy a newly formed watch station which helped the Army keep a watch on the Chinese activity far over the border with high accuracy.

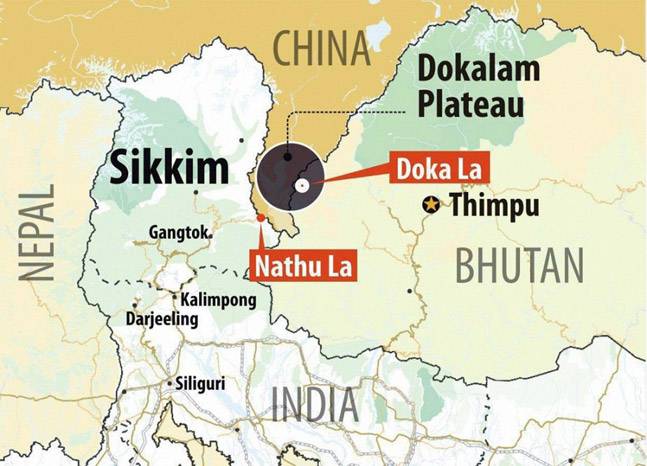

Doklam is plateau land in Bhutan and extremely strategic to both countries. It protects the vulnerable Siliguri Corridor (also called Chicken’s Neck), the only connection of Indian mainland to the northeast.

For China, however, the interest is for Chumbi valley. Doklam gives a commanding view of this valley which is strategic for bothsides. As the Government of Bhutan has cultivated special ties with India, the Indian Army extends protection to Bhutan whenever required. So, when the Chinese destroyed a few bunkers of Bhutanese Army and began road construction through Doklam as a part of their One Belt One Road (OBOR) project, the Bhutanese Army immediately asked India for backup.Two days after the infiltration by the Chinese Army, Indian forces managed to catch up and stop the PLA from infiltrating further.

The entire standoff continued for 73 days and has been one of the most dangerous situations near the country’s borders in recent times. The incident was solved diplomatically when both sides mutually agreed upon de-escalation and India agreed to attend the BRICS summit in China.

In recent times, the two countries have tried to nurture their bilateral relation through political meetings and even movies, like Kung Fu Yoga. However, at present, conditions have deteriorated due to the ongoing military standoff between the countries since May 2020.

The 2020 China–India skirmishes are part of an ongoing military standoff between China and India. Since 5 May 2020, Chinese and Indian troops have engaged in aggressive face-offs and skirmishes at locations along the Sino-Indian border.

This includes Pangong Tso Lake in Ladakh and the Tibet Autonomous Region; near the border between Sikkim. Additional clashes also took place at locations in eastern Ladakh along the Line of Actual Control (LAC).

The 2020 Galwan incident was the first military casualty after 1975 at the LAC between India and China. Twenty Indian Army personnel lost their lives at the hands of Chinese troops in the Galwan Valley of Ladakh. The incident represents a watershed in India’s relations with China and marks the end of a 45-year chapter which saw no armed confrontation involving loss of lives on the Line of Actual Control (LAC).

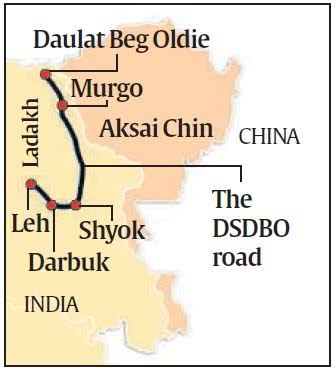

2020 Tensions have their roots, in both China and India’s expansion of military infrastructure along the LAC. India’s construction of a feeder road that would connect with the road from Darbuk-Shyok in Galwan Valley to Daulat Begh-Oldi was a trigger to Chinese Officials. China saw this as an aggressive tilt in India’s border strategy.

Galwan Valley’s strategic significance is because of its proximity to the vital road link to Daulat Beg Oldie (DBO)---the world’s highest airbase that lies close to the Line of Actual Control. This road strategically connects Leh to the Daulat Begh-Oldi military airbase allowing expedient mobility of troops and equipment to the LAC. Control over this road requires a control of the Galwan valley ridgeline where the June 15 clashes took place.

More importantly, control of the valley would provide India access to Aksai-Chin, which holds the Tibet-Xinjiang highway.

India’s changing Border StrategyIndia has been engaged in building up border infrastructure, including the all weather 255 km Darbul-Shayok- DBO road. Construction of the Darbuk-Shyok-DBO (DSDBO) road by India from Leh through Chushul — that leads to DBO, a military base with an airstrip — was completed last year. DSDBO runs almost parallel to the LAC and extends up to the base of the Karakoram pass. It reduced the travel time from Leh to DBO from the two days to just six hours. Adjacent Road and bridge construction works have recently been speeded up. And the Feeder Road which was being recently constructed by India was a part of this strategy. DSDBO passes near the Galwan Valley. For China, the Galwan region provides a vantage point overlooking the road to DBO. For India, control of the Galwan valley gives access to the Aksai Chin plateau, through which part of the Xinjiang-Tibet highway passes. |

West of DaulatBegh-Oldi is Gilgit-Baltistan, part of the POK (Pakistan Occupied Kashmir) region and part of CPEC (China Pakistan Economic Corridor). China is apprehensive of India’s strategic leverage in the region to compromise the CPEC. This could have a disastrous impact on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and China’s socio-economic and political stability.

This road also raises China’s trepidations regarding Aksai-Chin which it occupied after the 1962 war.

It is part of China’s ‘nibble and negotiates policy’. Their grand aim is to ensure that India does not build infrastructure along the LAC and change the status of Ladakh. Additionally, the remarks of Indian Union Minister, Amit Shah, in 2019, claiming the Chinese-occupied Aksai Chin to be within the territory of India had served China’s geopolitical and nationalistic insecurity no better.

The military talks to ease tensions between India and China are still underway. Recently, Five points of agreement were set forth after the sixth round of talks between the senior military commanders.

Though the two sides have inked towards a quick disengagement, there is no clear mention of final restoration of status quo in the five points. While diplomatic talks for de-escalation continue, there is uncertainty in the minds of many, awaiting the decisions that the countries will take.

Additionally there are other agreements related to the border question such as the 2005 "Agreement on the Political Parameters and Guiding Principles for the Settlement of the India-China Boundary Question".

There are five Border Personnel Meeting points (BPM) for holding rounds of dispute resolution talks among the military personnel. These are – Bum La and Kibithu in Arunachal Pradesh; Daulat Beg Oldi and Chushul in Ladakh, and Nathu La in Sikkim.

Historically, Beijing has made some offers on settling the border dispute. The simplest of them was the “package" deal.

It involved both the countries recognizing the status quo—Chinese occupation of Aksai Chin and Indian sovereignty over Arunachal Pradesh—on both fronts. This offer was first made by former Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai in 1960. This offer is arguably the best formula for settlement according to historian Mahesh Shankar because the region is not strategically important to India.

The offer was however rejected by former Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru as he was concerned that any concession, even in the west would only invite further aggression from Beijing all across the frontier.

Note: While Mahesh Shankar’s argument is indeed compelling, it must also be noted that according to Historian Sarvepalli Gopal New Delhi had always recognized the McMahon line in the west which awarded Arunachal Pradesh (then the North-East Frontier Agency) to India. Thus, a straight swap seemed unreasonable.

As Justice A.G. Noorani quoted:

“If a thief breaks into your house and steals your coat and your wallet, you don’t say to him that he can have the coat if he returns the wallet. You expect him to return all that he has stolen from you."

The second offer, which is still better for New Delhi than the “package" deal, is the “LAC plus solution"

The LAC-plus solution involved recognition of the status quo in the east and some concessions by China in the west. This offer, however, was not followed through on the Indian side.

And very soon, in the year 1985, China hardened its stand against this offer and it has roughly remained the same till date.

Beijing has specifically eyed Tawang, and asked India to put forward its offer on the eastern front, following which it would reveal what it could offer on the western front.

Any solution which requires India trading away any part of Arunachal Pradesh will not pass muster in New Delhi.

A resolution of the border dispute seems far away. Economist Arun Shourie summarized it aptly:

We really should not be in a hurry to ‘solve’ the dispute—especially not when the distance between China and India is as vast as it has become;

Secondly, an agreement is worth something only if we are sure that the other side would not violate it. And we can actually make it expensive for the other side if it violates the agreement.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved