Description

Disclaimer: Copyright infringement not intended

Context

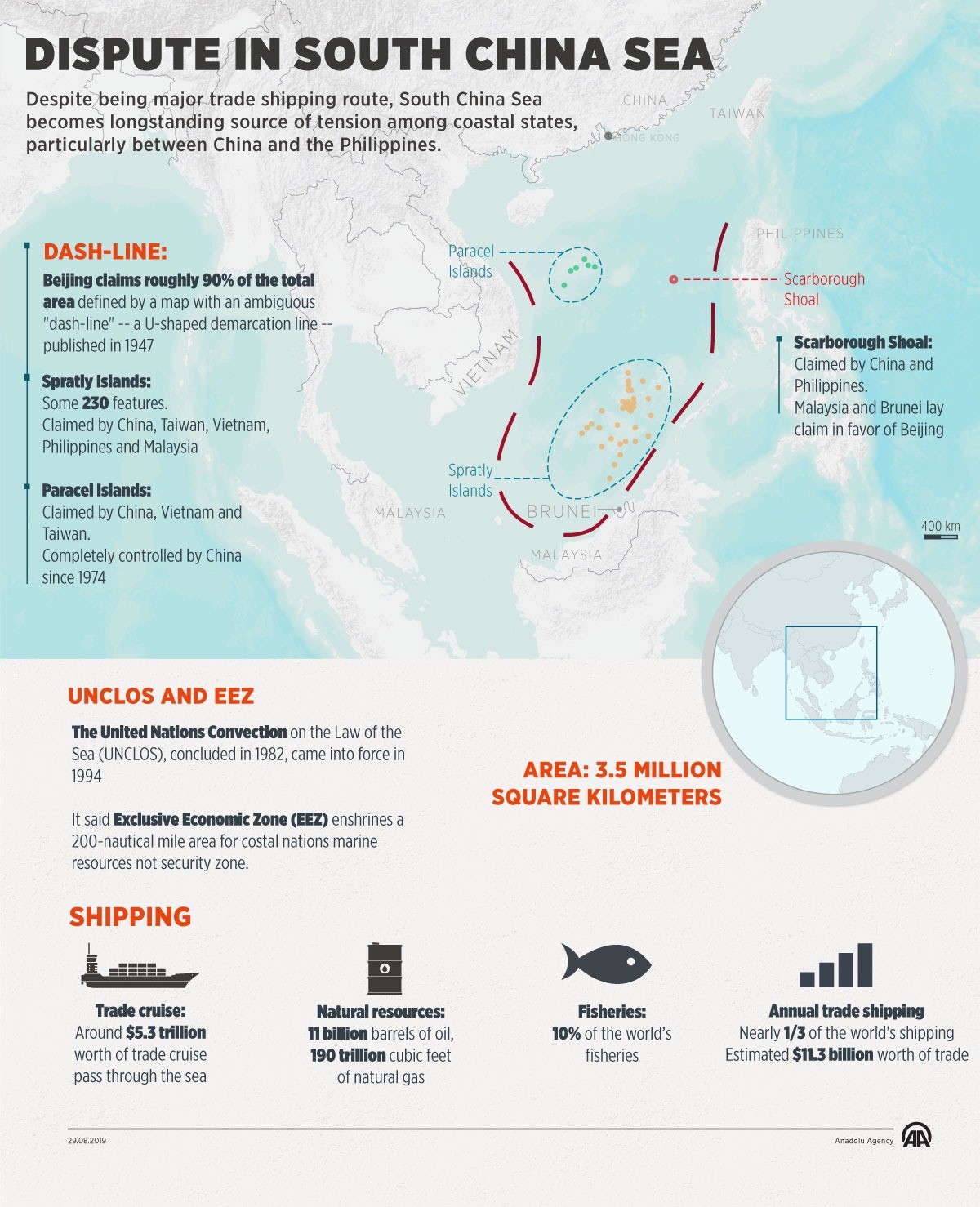

- A fresh controversy broke out recently after China installed a barricade near the South China Sea’s Scarborough Shoal.

- Both countries have been embroiled in a tussle over the shoal’s territorial claim since 2012.

- The development once again brought the South China Sea dispute to the forefront.

MUST READ ARTICLES ON SOUTH CHINA SEA:

https://www.iasgyan.in/daily-current-affairs/south-china-sea-23

https://www.iasgyan.in/daily-current-affairs/south-china-sea

What is the South China Sea Dispute?

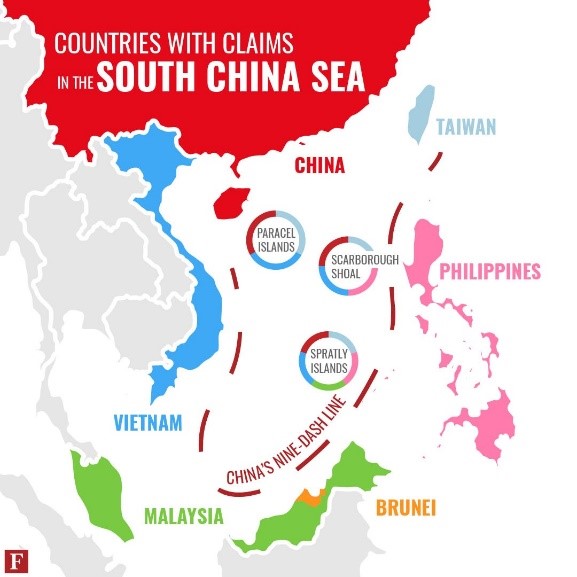

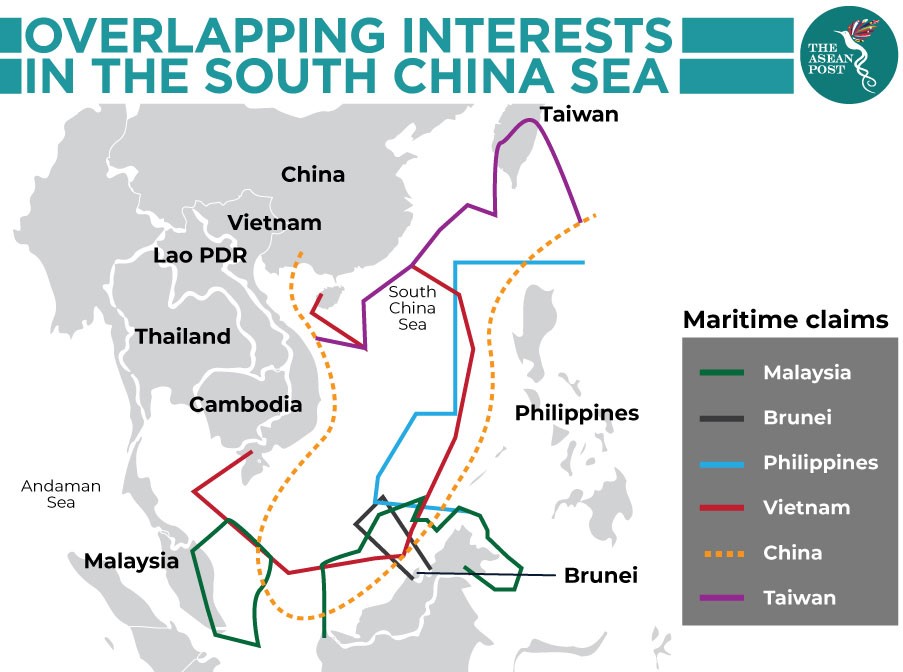

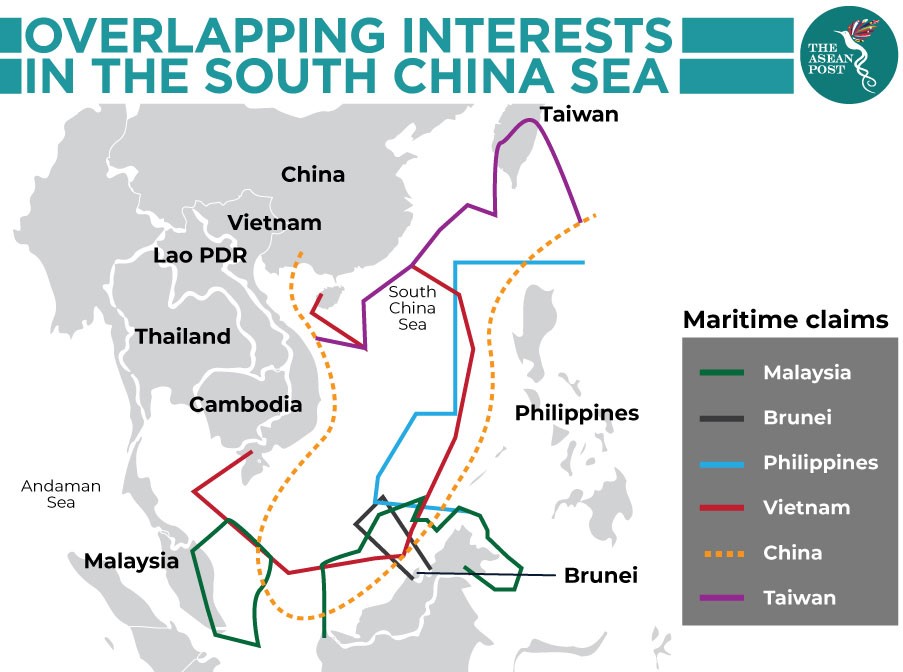

- The South China Sea is situated just south of the Chinese mainland and is bordered by the countries of Brunei, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam.

- The countries have bickered over territorial control in the sea for centuries, but in recent years tensions have soared to new heights.

Reason behind the rise

- The South China Sea is one of the most strategically critical maritime areas and China eyes its control to assert more power over the region.

- Due to its economic and geostrategic importance, the South China Sea becomes a venue of several complex territorial disputes that have been the cause of political as well as military conflict and tension within the region and throughout the Indo-Pacific.

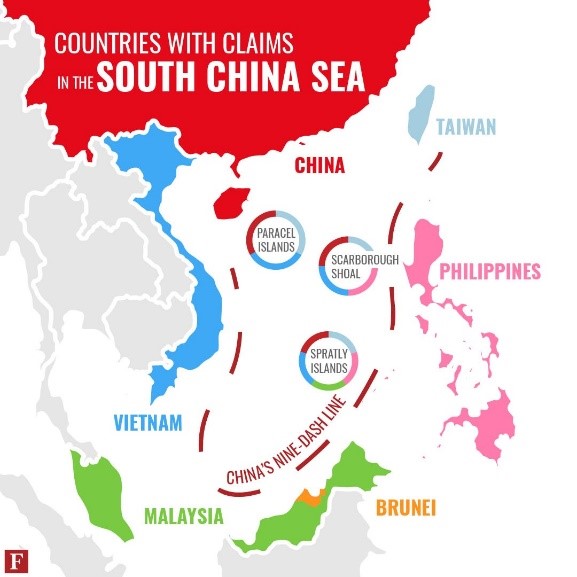

Nine-Dash Line

- In 1947, the country, under the rule of the nationalist Kuomintang party, issued a map with the so-called “nine-dash line”.

- The line essentially encircles Beijing’s claimed waters and islands of the South China Sea — as much as 90% of the sea has been claimed by China.

- The line continued to appear in the official maps even after the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) came to power.

- The line runs as far as 2,000 km from the Chinese mainland to within a few hundred kilometers of the Philippines, Malaysia and Vietnam.

- In the past few years, China has also tried to stop other nations from conducting any military or economic operation without its consent, saying the sea falls under its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

Response of Neighbouring Countries and China’s repurcussions

- China’s sweeping claims, however, have been widely contested by other countries. In response, China has physically increased the size of islands or created new islands altogether in the sea, according to the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR).

- China has also constructed ports, military installations, and airstrips—particularly in the Paracel and Spratly Islands, where it has twenty and seven outposts, respectively.

- China has militarised Woody Island by deploying fighter jets, cruise missiles, and a radar system.

- To challenge China’s assertive territorial claims and protect its own political and economic interests, the US has intervened in the matters.

- It has not only increased its military activity and naval presence in South Asia but also provided weapons and aid to China’s opponents.

Importance of the South China Sea

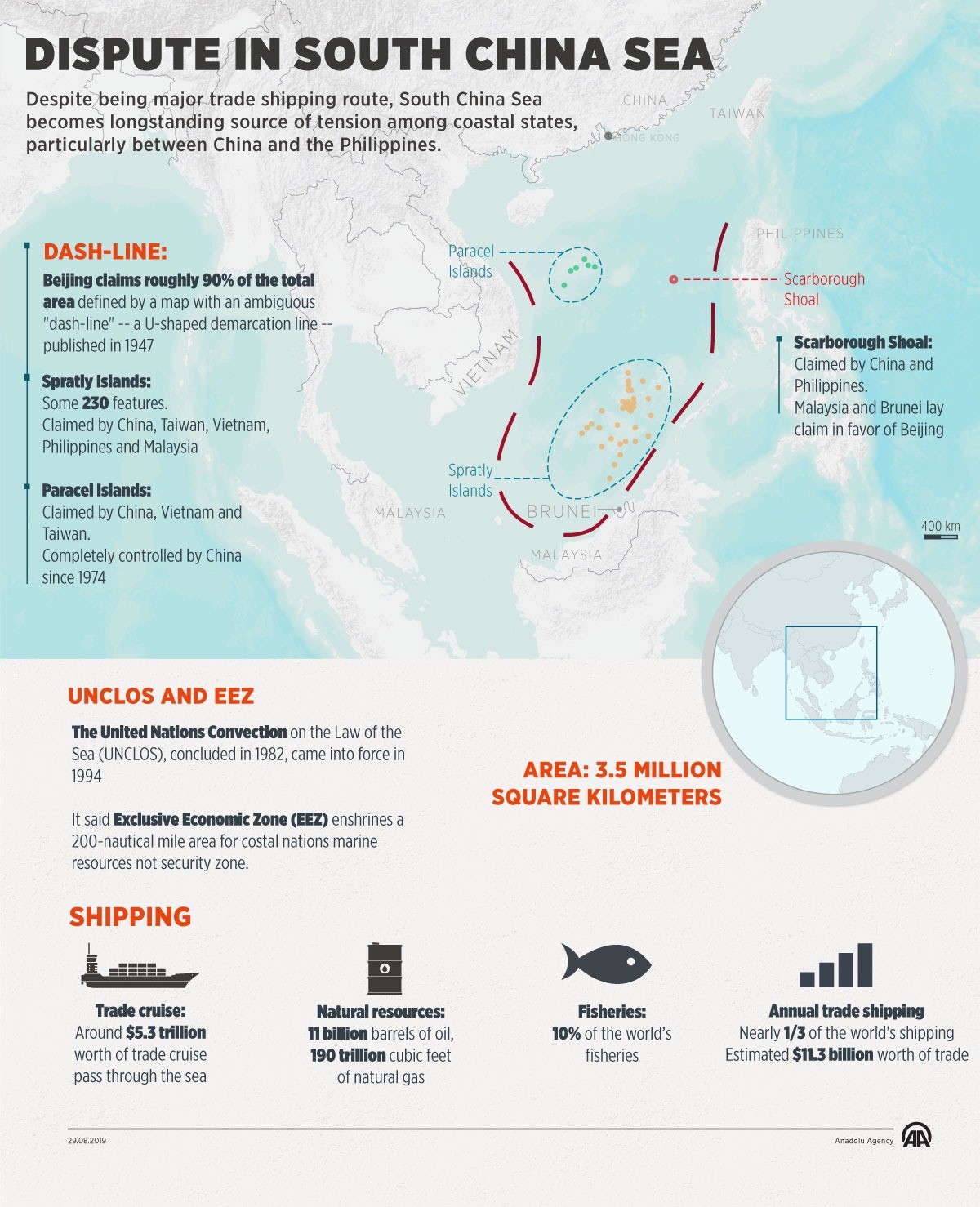

- There are 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas in deposits under the South China Sea, according to the estimates of the United States Energy Information Agency.

- Moreover, the sea is home to rich fishing grounds — a major source of income for millions of people across the region. The BBC reported that more than half of the world’s fishing vessels operate in this area.

- Most significantly, the sea is a crucial trade route. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development estimates that over 21% of global trade, amounting to $3.37 trillion, transited through these waters in 2016.

Shipping

- Spreading over the 3.5 million square kilometers, nearly one-third of the world's shipping, estimated $11.3 billion worth of trade annually pass through this waterway according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

- Japan and South Korea heavily rely on the South China Sea as an export route and for their supply of fuels and raw materials.

- Around $5.3 trillion worth of trade cruise through the South China Sea annually, with $1.2 trillion of that total accounting for trade with the U.S., said the Washington-based think tank in a report, "How Much Trade Transits the South China Sea?", published in 2017.

- Fisheries

- The South China Sea also contains rich, though, unregulated and over-exploited fishing grounds, containing an estimated 10% of the world’s fisheries, the report said.

Natural resources

- The South China Sea holds significant reserves of undiscovered oil and gas, which is an aggravating factor in maritime and territorial disputes, it said.

- It covers an estimated 11 billion barrels of oil, plus an estimated 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, according to the Energy Information Administration.

- The major island and reef formations in the South China Sea are the Spratly Islands, Paracel Islands, Pratas, the Natuna Islands and Scarborough Shoal.

DISPUTES

- China claims nearly all of the 3.5-million-square-kilometer South China Sea, which is one of the fiercely contested regions in the world.

Dash-line

- Beijing claims roughly 90% of the total area defined by a map with an ambiguous "dash-line" -- a U-shaped demarcation line -- published in 1947.

- The Paracel Islands, along with the Spratly group to the south, are located within China’s so-called nine or ten "dash-line".

Spratly Islands

- China, Taiwan and Vietnam, each claims sovereignty over all the Spartly’s some 230 features, according to Lowy Institute, an Australia-based think-tank.

- However, the Philippines claims 53 features and Malaysia claims 12. Vietnam occupies 27 features, followed by China with eight, the Philippines with seven, Malaysia with five, and Taiwan with one, said the institute.

- China has been building artificial islands, containing port facilities, military buildings and an airstrip in the Spratly archipelago, a disputed scattering of reefs and islands.

Paracel Islands

- The Paracel Islands are the subject of overlapping claims by China, Vietnam and Taiwan. But the group of islands is completely controlled by Beijing since 1974, the institute said.

Scarborough Shoal

- Both the Philippines and China have competing for claims over the Scarborough Shoal, while Malaysia and Brunei laying claim to maritime territory in the sea to assert their sovereignty. The Scarborough Shoal is the scene of ongoing tensions between Beijing and Manila. Since a standoff in 2012, Chinese vessels have de facto controlled the waters around the reef, according to the Australian think-tank.

- In 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague concluded that Beijing's claims to areas of the resource-rich sea have no legal basis. The arbitration was launched by the Philippines, while China rejected the ruling.

UN law and Exclusive Economic Zone

- As the disputes over the South China Sea escalated day by day, the global community took several steps to reach a settlement. The UN concluded a law in 1982 due to establish a legal framework to balance the economic and security interest of coastal states.

- The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which came into force in 1994, enshrines a 200-nautical mile area to extend sole exploitation rights to coastal nations over marine resources.

- However, the area, officially called as the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), was never intended to serve as a security zone, and UNCLOS also guarantees wide-ranging passage rights for naval vessels and military aircraft.

- Despite being signed and ratified by all concerned countries in the region, the interpretation of UNCLOS in the South China Sea is still fiercely disputed.

Likely Solution

- Each claimant keeps what it currently occupies and drops its claims to the other features. There is a legal name for this principle: uti possidetis, ita possideatis – what you have is what you keep.

- No state would have to suffer the indignity or strategic disadvantage of withdrawing from any feature that they currently occupy. Each state would simply have to acknowledge reality – that they are never going to acquire all the rocks and reefs they rhetorically claim. This is already implicit in the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (the DoC) adopted by ASEAN and the PRC in 2002.

- Under Article 5, all the signatories are committed to “self-restraint in the conduct of activities that would complicate or escalate disputes and affect peace and stability including, among others, refraining from action of inhabiting on the presently uninhabited islands, reefs, shoals, cays, and other features and to handle their differences in a constructive manner.

- This would be a price worth paying if the quid pro quo is regional stability. For Vietnam, recognition of Chinese possession of the Paracels would be painful but it could unlock an agreement between Vietnam and China over the maritime boundary at the mouth of the Gulf of Tonkin and areas further south. This would, in effect, end China’s U-shaped line claim and open areas of the sea for Vietnamese energy exploration and fisheries.

Way Ahead

- In the current geopolitical situation, there is a clear incentive for Southeast Asian governments to begin a process of formally recognizing each other’s occupations in the Spratly Islands. Such mutual recognition would help solidify their own claims and facilitate the creation of a clearer negotiating position with China.

- Some cases will be more difficult to resolve than others, and the sequencing of recognition will need to take this into account. Non-governmental organizations could play a key role in helping governments scope out likely obstacles and pitfalls and in generating support for the necessary political compromises.

India and South China Sea

- India has historically taken a neutral position in the disputes along the South China Sea involving China and countries of Southeast Asia, even as the tensions have threatened the security in the region.

- In more recent times, however, there has been a noticeable change in India’s stance. This brief ponders this shift: the rationale behind India’s responses vis-à-vis the disputes, and their implications on the country’s ‘Act East’ and Indo-Pacific policies.

India’s Stakes in the South China Sea

- India uses the SCS waterways—the second-most used in the world—for trade worth nearly US$200 billion every year. Nearly 55 percent of India’s trade with the Indo-Pacific region pass through these waters.

- Overall, one-third of the world’s shipping pass through these SLOCs, carrying over US$3 trillion worth of trade each year, including most of the world’s requirement for vital commodities like energy and raw materials.

India itself signed an agreement with Vietnam in October 2011 to expand and promote oil exploration in the South China Sea. While China has always objected to India’s oil exploration activities in the Vietnamese waters in the SCS, India reaffirmed its intent to pursue such activities.

- For India, its economic vitality rests on assured supply of energy and safe and secure trading routes in the region, including the Straits of Malacca. It has high stakes in keeping the sea lanes open in the SCS—the junction between the Indian and Pacific Oceans—and many other countries do as well.

- Clearly, the South China Sea is becoming a factor in India’s own strategic calculations and strategic debates, and India is becoming a factor in the strategic calculations of South China Sea states.

- India engages with the region through regular naval deployments, visits and exercises in these waters, through established and growing strategic-military partnerships with the littoral states, involvement in oil exploitation in these waters, and diplomatic discussions.

- As the Indian Navy also operates in the Western Pacific, secure access through the waters of the South China Sea becomes important.

- The SCS has the potential to enhance regional growth and further India’s engagement with Southeast Asia.

- India’s interest in the Indo-Pacific is known, and India views the region as “an integrated and organic maritime space with the ASEAN at its centre.”

- ASEAN and the far-eastern Pacific are the focus areas of India’s Act East policy, and the Southeast Asian commons are a “vital facilitator of India’s future development.”

- As ASEAN countries’ relations with China come under more strain, India is eager to play the role of a responsible regional stakeholder that can help find a balance amidst the disputes.

India’s Historical Approach to SCS Disputes

Diplomatic tact

- New Delhi has tried to balance the many competing interests in the South China Sea and not offend Beijing. India’s concern is that if it wades too deeply in SCS affairs, China might heighten its own naval operations in the Indian Ocean.

- India’s stance in the South China Sea disputes was indicated in the joint ASEAN-India Vision Statement of December 2012. It stressed “India’s role in ensuring regional peace and stability, and for that we agree to promote maritime cooperation to address common challenges on maritime issues.”

Naval posturings

- India’s naval presence in the South China Sea has been bigger. The Indian Navy has been engaging in deployments in the disputed waters since 1995. These deployments include unilateral appearances by the Indian Navy, bilateral exercises, friendly port calls, and transit through these waters.

Table 1. India’s Naval Exercises and Deployments in the Indo-Pacific

|

Year

|

Operations and overseas deployments in the Eastern Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific

|

|

2004

|

Deployments of a five-ship flotilla (two Kashin class destroyers, INS Ranjit and Ranvijay; the frigate Godavari; the missile corvette Kirch; the offshore patrol vessel Sukanya; and the fleet tanker Jyoti) to the South China Sea.

|

|

2015

|

INS Kamorta was deployed to participate in the Langkawi International Maritime and Aerospace Exhibition (LIMA-15) scheduled from 17 – 21 Mar 2015.

|

|

2015

|

INS Kamorta, Satpura took part in SIMBEX-15 in May 2015.

|

|

2015

|

INS Saryu, participated in a week-long ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) Disaster Relief Exercise (DiREx) 2015 conducted in Penang, Northern Malaysia from 24 to 28 May 2015.

|

|

2016

|

INS Airavat participated in the ADMM Plus (ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus) Exercise on Maritime Security and Counter Terrorism (Ex MS & CT) from 01 to 09 May 2016, which commenced at Brunei and culminated at Singapore, with various drills and exercises in the South China Sea.

|

|

2016

|

The Indian Navy’s Eastern Fleet sailed out on 18 May 2016 on a two-and-a-half-month-long operational deployment to the South China Sea and North West Pacific. During this overseas deployment, the ships of Eastern Fleet made port calls at Cam Rahn Bay (Vietnam), Subic Bay (Philippines), Sasebo (Japan), Busan (South Korea), Vladivostok (Russia), and Port Klang (Malaysia).

|

|

2016

|

INS Sumedha arrived in Padang, Indonesia on 10 Apr 2016 to participate in the International Fleet Review and the second edition of the Multilateral Naval Exercise KOMODO (MNEK).5

|

|

2019

|

INS Kamorta exercised with the Indonesian Warship KRI Usman Harun in the Bay of Bengal as part of the Indian Navy – Indonesian Navy Bilateral Exercise ‘Samudra Shakti’ from 6 to 7 November 2019.

|

|

2020

|

The 30th edition of the India-Thailand Coordinated Patrol (Indo-Thai CORPAT) between the Indian Navy and the Royal Thai Navy was conducted from 18 – 20 November 2020.

|

|

2020

|

The 35th edition of the India-Indonesia Coordinated Patrol (IND-INDO CORPAT) between the Indian Navy and the Indonesian Navy was conducted from 17 to 18 December 2020.

|

|

2020

|

The Indian Navy (IN) undertook a Passage Exercise (PASSEX) with Russian Federation Navy (RuFN) in the Eastern Indian Ocean Region (IOR) from 4 to 5 December 2020.

|

|

2020

|

The 2020 edition of SIMBEX in the Andaman Sea

|

|

2020

|

2nd edition of India, Singapore and Thailand Trilateral Maritime Exercise SITMEX, from 21 to 22 November in the Andaman Sea.

|

|

2020

|

The Indian Navy carried out a military exercise with a US Navy carrier strike group led by the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier USS Nimitz off the coast of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

|

|

2020

|

The IN undertook PASSEX with the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) in the East Indian Ocean Region from 23 to 24 September 2020.

|

|

2021

|

India and the US on March 28 kicked off a two-day naval exercise in the eastern Indian Ocean region.

|

Source: Compiled by the author from the Indian Navy website, https://www.indiannavy.nic.in/operations/10/page/1/0

- There has been a distinct naval dimension in India’s Act East policy.

- The traditional clear distinctions, then, between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific are beginning to blur. India is now looking beyond the Strait of Malacca to include the South China Sea in its national security calculus.

Why the Shift in India’s Approach?

The momentum of India’s ‘Act East’ policy

Bilateral Trade

- Even with India pulling out of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the country’s existing engagement with ASEAN is back in focus.

- A 2019 industry study suggests that India’s bilateral trade with the ASEAN economies would double by 2025 to US$ 300 billion from the 2018 level of US$ 142 billion.

Table 2. India-ASEAN Trade (2013-2020)

|

India’s trade with ASEAN

|

2013-14

|

2014-15

|

2015-16

|

2016-17

|

2017-18

|

2018-19

|

2019-20

|

|

Exports (US$ billions)

|

33.13

|

31.81

|

25.13

|

30.96

|

34.20

|

37.47

|

31.55

|

|

% Growth

|

0.38

|

-3.99

|

-21.00

|

23.19

|

10.47

|

9.56

|

-15.82

|

|

Imports (US$ billions)

|

41.28

|

44.71

|

39.91

|

40.62

|

47.13

|

59.32

|

55.37

|

|

% Growth

|

-3.71

|

8.33

|

-10.75

|

1.77

|

16.04

|

25.86

|

-6.66

|

|

Total (US$ billions)

|

74.41

|

76.53

|

65.04

|

71.58

|

81.34

|

96.80

|

86.92

|

|

Trade Balance (US$ billions)

|

-8.14

|

-12.90

|

-14.78

|

-9.66

|

-12.93

|

-21.85

|

-23.82

|

Source: https://commerce.gov.in/about-us/divisions/foreign-trade-territorial-division/foreign-trade-asean/

- The ASEAN-India Free Trade Agreement (AIFTA) of 2009 has boosted bilateral trade.

- India’s exports to ASEAN in 2019-20 were worth US$31.49 billion, while its imports from the bloc reached US$55.37 billion.

- In comparison, China became Southeast Asia’s largest trade partner in the January-June 2020 as the trade war with the US has forced Beijing to recalibrate its global supply chains. China’s total imports and exports with the ASEAN increased by 2 percent on the year to $297.8 billion. The bloc accounted for 14.7 percent of China’s overall trade for the period, up from 14 percent in 2019.

Defence Links

- India’s defence links with ASEAN have increased over time, in particular in the naval domain.

- With countries like Vietnam, India has been deepening its defence cooperation since the 1990s.

- In December 2020 seven agreements were inked between India and Vietnam. These included one on implementing arrangements on defence industry cooperation, and another on nuclear cooperation between India’s Atomic Energy Regulatory Board and Vietnam’s Agency for Radiation and Nuclear Safety.

- The summit also provided an opportunity to hand over one high-speed guard boat to Vietnam, launch of two other vessels manufactured in India, and keel-laying of seven vessels being manufactured in Vietnam under the US$100-million defence Line of Credit being extended by India. The two sides also agreed to explore new and practical collaborations to build capacities in the areas of blue economy, maritime security and safety, marine environment and sustainable use of maritime resources, and maritime connectivity.

- Meanwhile, the mainstay of India-Philippines defence relations is underlined by capacity-building and training, exchange visits of delegations, and naval and coast guard ship visits.

- Indian Navy and coast guard ships regularly visit the Philippines and hold consultations with their counterparts.

- In February 2019, ICGS Shaunak visited Manila on the occasion of Indian Coast Guard Day; earlier, Indian Navy Vessel, INS Rana visited Manila from 23-26 October 2018.

- These are just some of the most important examples of how India has deepened bilateral and multilateral engagements with the Southeast Asian countries.

- Mutually supporting each other in the South China Sea and the Bay of Bengal, has allowed the ASEAN nations and India to sustain their relations.

- It is only a matter of time before India’s naval capabilities, maritime infrastructure, closer naval partnerships and capacity-building programmes progress into stronger cooperative partnerships in the region.

- The collaborative interests between the ASEAN countries and India are further evident in the prioritisation of freedom of navigation and overflight in the South China Sea.

China’s belligerence

- China’s growing assertiveness in the South China Sea is a cause of concern for India.

- The ‘Incremental Encroachment Strategy’ that China is exhibiting in the South China Sea, East China Sea (ECS) and Ladakh is a serious concern not only for the countries directly affected by overlapping EEZs or unsettled borders, but also for the rest of the world.

- There is rising incidence of Chinese intelligence ship sightings in the IOR.

- Chinese Dongdiao class intelligence-gathering ships – known earlier to stalk US, Australian and Japanese warships in the Western Pacific – are now operating in the waters of the Eastern Indian Ocean, keeping an eye on India’s naval movements.

- In response, the Indian Navy intends to maintain a presence in the South China Sea.

- Vietnam and other ASEAN nations have requested India’s assistance in stabilising naval cooperation and balancing China’s assertiveness in the region.

- Philippines’ former Deputy Minister for international economic relations, had once stated: “India should go East, and not just Look East.”

Stronger positions from other extra-regional players

- India is looking to work more closely with like-minded countries in the Indo-Pacific, and is entering into issue-based minilateral partnerships like Japan-Australia-India, India-Australia-France, and the Quad.

- The Quad, since its revival in 2017, has reiterated its aim of working towards a free and open Indo-Pacific.

- Of the four partner countries, only India has not directly spoken about the South China Sea disputes. However, following the Galwan Valley clash of June 2020, a change in India’s attitude towards China started becoming more noticeable, even in relation to the SCS disputes.

.jpg)

Conclusion

- Policy researchers in New Delhi have long advocated that given China’s growing presence in the Indian Ocean region, which is considered as India’s primary theatre of interest, it is time for India to also increase its presence and influence in China’s backyard—the Western Pacific.

- From speaking up on the South China Sea when its interests in oil exploration in the disputed waters in Vietnam were encroached upon, to releasing official statements that call attention to Chinese encroachments in the disputed territories—a tilt is noticeable in the Indian government’s approach.

- For having a stronger presence in this part of the world and gaining greater trust from its Southeast Asian neighbours, India would need to interact and engage more as part of its Act East policy along with the other Quad members that have similar influence in the region.

- India must harden its stance on the South China Sea conflicts, and work towards developing a composite strategy on dealing with the issues to make its presence felt in the region and, ultimately, craft a more meaningful Indo-Pacific strategy.

|

PRACTICE QUESTIONS

Q. India has historically taken a neutral position in the disputes along the South China Sea involving China and countries of Southeast Asia, even as the tensions have threatened the security in the region. In more recent times, however, there has been a noticeable change in India’s stance. Why the Shift in India’s Approach? Discuss in the context of ‘Act East’ and Indo-Pacific policies.

Q. The South China Sea is becoming a factor in India’s own strategic calculations and strategic debates, and India is becoming a factor in the strategic calculations of South China Sea states. Elucidate.

Q. India must harden its stance on the South China Sea conflicts, and work towards developing a composite strategy on dealing with the issues to make its presence felt in the region and, ultimately, craft a more meaningful Indo-Pacific strategy. Do you agree?

|