The CVC, made statutory after the Vineet Narain judgment, supervises the CBI and advises on vigilance. However, advisory powers, no independent investigation wing, limited jurisdiction, and delays weaken effectiveness. Reforms should expand jurisdiction and grant prosecutorial powers, learning from Hong Kong’s ICAC.

Copyright infringement not intended

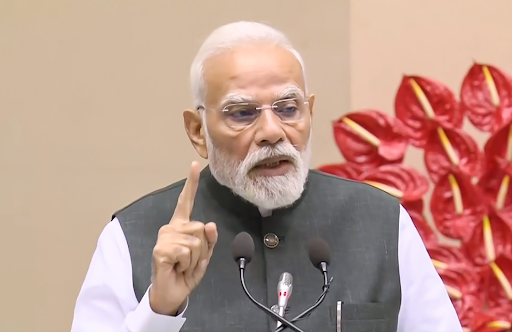

Picture Courtesy: PIB

The President of India appointed Shri Praveen Vashista as Vigilance Commissioner in the Central Vigilance Commission.

The CVC was set up in 1964 through an executive resolution.

Its creation was based on the recommendations of the Committee on Prevention of Corruption, headed by K. Santhanam.

The CVC was granted statutory status with the enactment of the CVC Act, 2003, following the Supreme Court's directives in the Vineet Narain case (1997) to ensure its independence from executive control.

Composition

A Central Vigilance Commissioner (Chairperson) and not more than two Vigilance Commissioners.

Appointment

Appointed by the President of India on the recommendation of a three-member committee consisting of:

Tenure

Four years or until they attain the age of 65 years, whichever is earlier.

Reappointment

They are not eligible for reappointment in any central or state government service after their tenure.

Superintendence over CBI

The CVC exercises superintendence over the CBI for cases investigated under the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988, ensuring fair investigations without executive influence.

Inquiry and Investigation

The CVC can order corruption inquiries or investigations, but it must depend on the CBI or departmental Chief Vigilance Officers (CVOs) to conduct them, as the CVC itself is not an investigative agency.

Advisory Role

The CVC advises Central Government departments on vigilance matters, and its annual report to the President details non-accepted advice to ensure parliamentary accountability.

Whistleblower Protection

It is the designated agency to receive and act on complaints under the Public Interest Disclosure and Protection of Informers (PIDPI) Resolution, 2004.

Powers of a Civil Court

While conducting inquiries, the CVC has the powers of a Civil Court, allowing it to summon witnesses, require the discovery of documents, and receive evidence on affidavits.

Advisory Nature: The CVC's recommendations are not binding on the government. Departments can choose to reject its advice, which dilutes its authority.

No Independent Investigation Wing: Its dependence on the CBI and departmental CVOs for investigations can lead to delays and potential conflicts of interest.

Limited Jurisdiction: Its authority is restricted to officials of the Central Government and Public Sector Undertakings. It has no jurisdiction over state government officials, ministers, or the judiciary.

No Power to Prosecute: The CVC can only recommend the registration of a Regular Case (RC) by the CBI or disciplinary action. It lacks the power to initiate criminal proceedings or prosecute offenders directly.

Resource Constraints: The commission faces a shortage of financial and human resources, which hampers its capacity to handle the high volume of complaints effectively.

Grant Prosecutorial Powers: Empowering the CVC with the authority to launch prosecutions would make it a more effective deterrent against corruption.

Strengthen Autonomy: Granting the CVC its own independent investigation wing would reduce its dependence on other agencies and ensure faster, more impartial inquiries.

Expand Jurisdiction: Broadening the CVC's ambit to include state government employees and entities funded by the central government would create a more uniform anti-corruption framework.

Make Advice Binding: Implementing a mechanism to make the CVC's advice binding on government departments would ensure that its findings lead to concrete action.

Enhance Resources: The commission must be adequately funded and staffed to handle its workload efficiently and invest in modern investigative technologies.

What India Can Learn from Global Anti-Corruption Agencies?

|

|

CVC (India) |

ICAC (Hong Kong) |

CPIB (Singapore) |

|

Investigative Powers |

Dependent on CBI/CVOs |

Independent investigation wing with powers of search, seizure, and arrest |

Independent investigation wing with vast powers, including arrest without a warrant |

|

Prosecutorial Powers |

Only recommendatory |

Can initiate prosecution |

Investigates and refers cases to the Public Prosecutor |

|

Jurisdiction |

Limited to Central Govt. & PSUs |

Covers both public and private sectors |

Covers both public and private sectors |

|

Strategy |

Mainly punitive and advisory |

Three-pronged: Investigation, Prevention, and Community Education |

Focused on robust investigation and prevention |

The CVC must be statutorily empowered with independent investigative machinery and binding authority to become a formidable anti-corruption body, transitioning it from a mere advisory entity to an effective enforcement agency.

Source: PIB

|

PRACTICE QUESTION Q. Analyze the role of the Central Vigilance Commission (CVC) in ensuring integrity in public administration. Does its advisory nature limit its effectiveness? 150 words |

The CVC is India's apex integrity institution, created to address governmental corruption. It monitors all vigilance activities under the Central Government and advises various authorities on planning and executing their vigilance work.

The CVC is a statutory body. It was initially established by an executive resolution in 1964 but was granted statutory status by the Central Vigilance Commission Act, 2003.

The Central Vigilance Commissioner is appointed by the President of India based on the recommendation of a three-member committee consisting of the Prime Minister, the Union Minister of Home Affairs, and the Leader of the Opposition in the Lok Sabha.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved