NEW LABOUR CODES DECODED

Labour falls under the Concurrent List of the Constitution. Therefore, both Parliament and state legislatures can make laws regulating labour. The central government has stated that there are over 100 state and 40 central laws regulating various aspects of labour such as resolution of industrial disputes, working conditions, social security and wages. The Second National Commission on Labour (2002) found existing legislation to be complex, with archaic provisions and inconsistent definitions. To improve ease of compliance and ensure uniformity in labour laws, it recommended the consolidation of central labour laws into broader groups such as: (i) industrial relations, (ii) wages, (iii) social security, (iv) safety, and (v) welfare and working conditions.

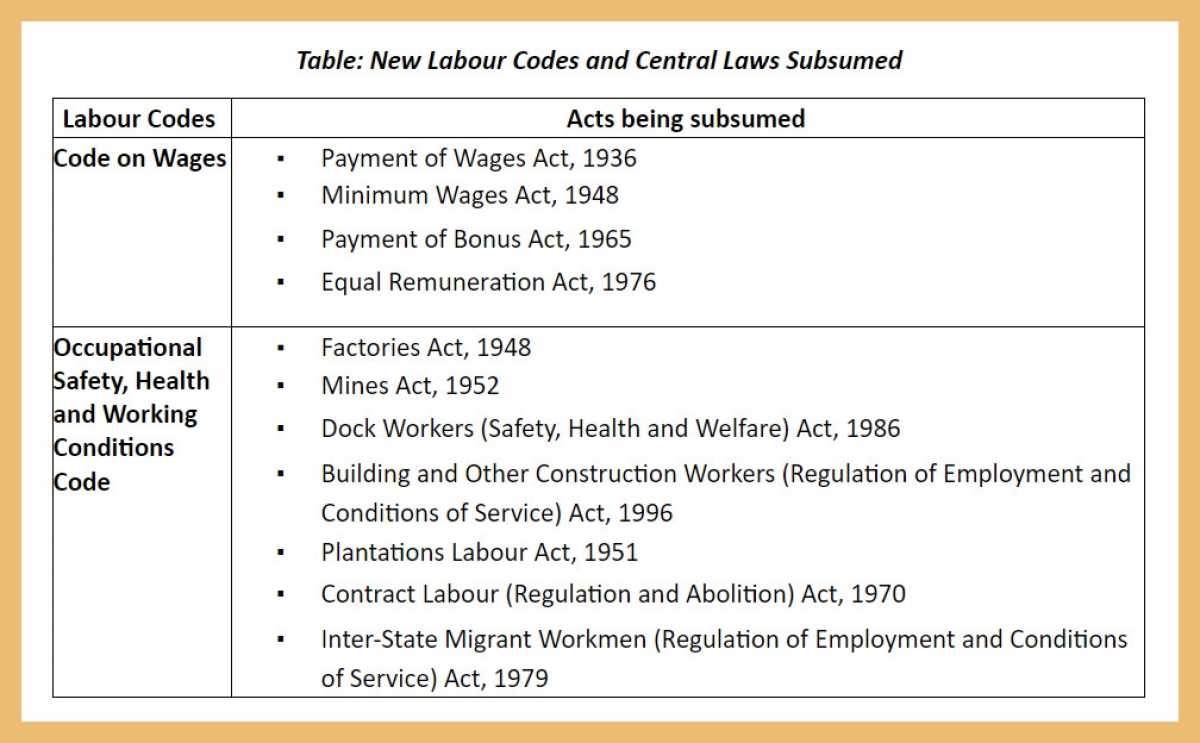

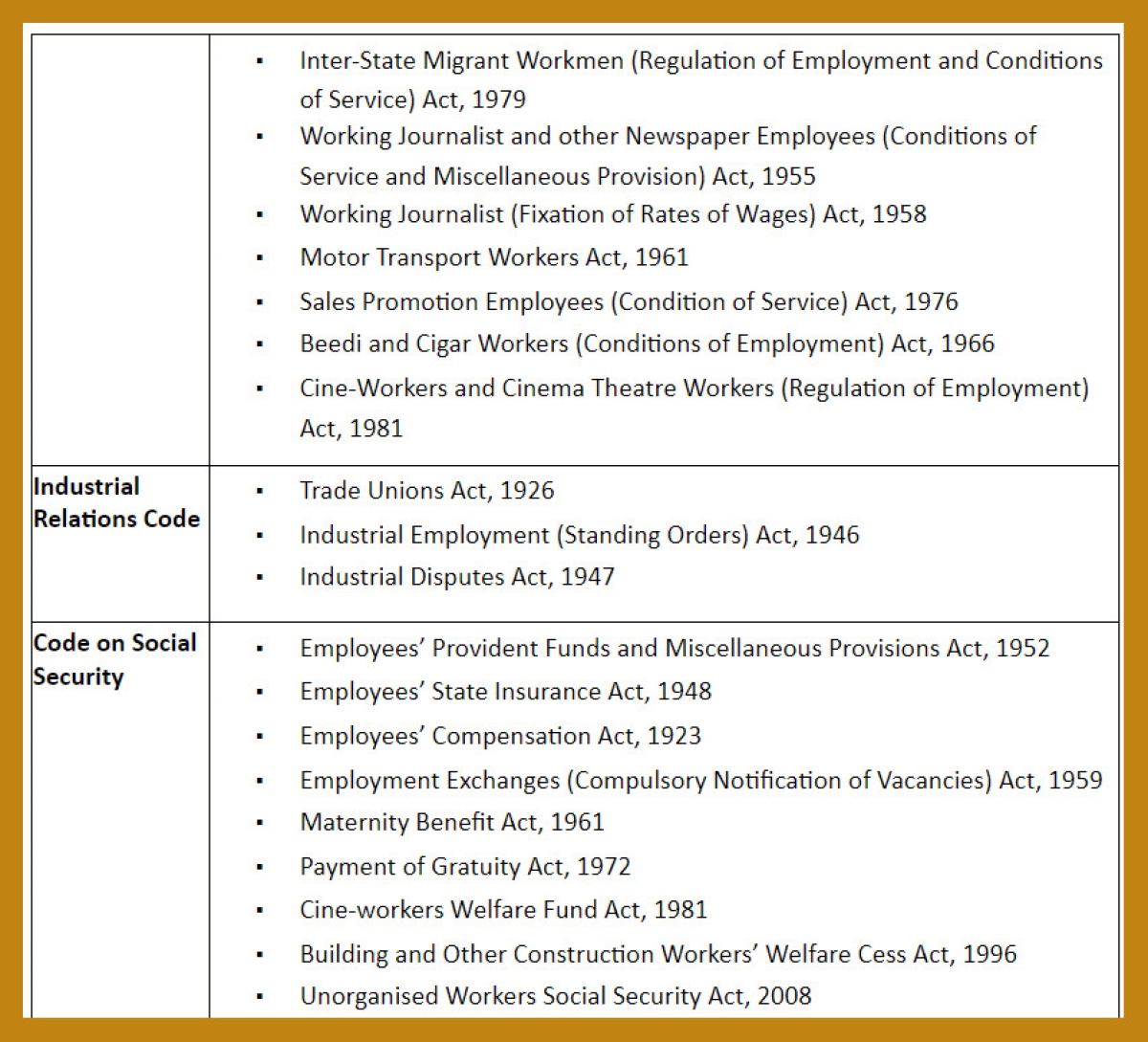

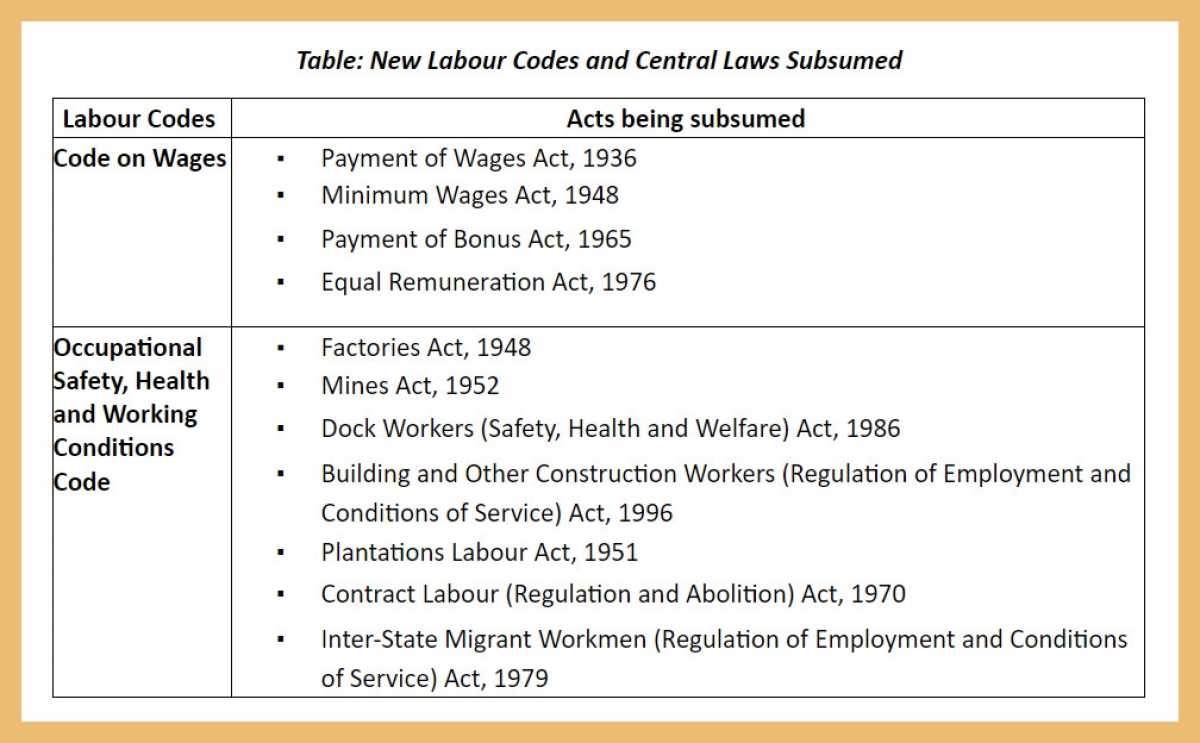

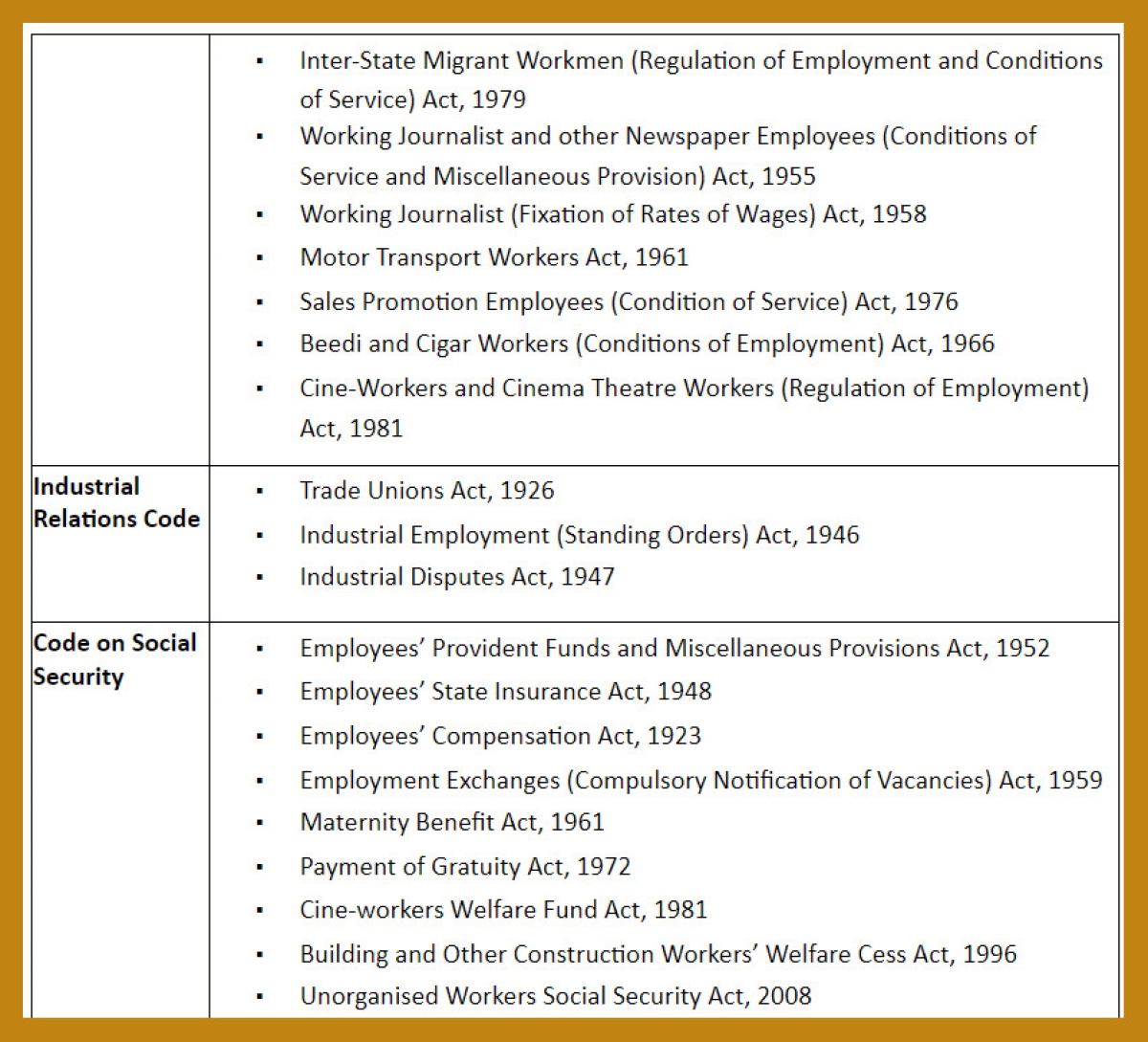

In 2019, the Ministry of Labour and Employment introduced four Bills to consolidate 29 central laws. These Codes regulate: (i) Wages, (ii) Industrial Relations, (iii) Social Security, and (iv) Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions. While the Code on Wages had been passed by Parliament in 2019, Bills on the other three areas were passed this year.

Giving equal importance to ‘Shramev Jayate’ and ‘Satyamev Jayate’ and taking into account the holistic development of the country by keeping the labour interest uppermost in the mind, 29 labour laws have been subsumed in the simplified, easy to understand transparent 4 labour codes.

NEED FOR LABOUR REFORMS

- Simplification of labour laws: It observed that there are numerous labour laws, both at the centre and in states. Further, labour laws have been added in a piecemeal manner, which has resulted in these laws being ad-hoc, complicated, mutually inconsistent with varying definitions, and containing outdated clauses.

- Facilitating job creation while protecting work: The 6th Economic Census (2013-14) reported that there were 5.9 crore establishments in India employing 13.1 crore people (of which 72% were self-employed and 28% hired at least one worker). A total of 79% workers were in establishments with less than ten workers. The central challenge to labour regulation is to provide sufficient rights to workers while creating an enabling environment that can facilitate firm output and growth, leading to job creation. Firms should find it easy to adapt to changing business environment and be able to change their output (and employment) levels accordingly. At the same time, workers need protection of assured minimum wages, social security, reduction in job insecurity, health and safety standards, and a mechanism for ensuring collective bargaining rights. This would also require a labour administration that effectively manages conflicts and ensures the enforcement of rights.

- Coverage of establishments under labour laws: Most labour laws apply to establishments over a certain size (typically 10 or over). Low numeric thresholds may create adverse incentives for establishments sizes to remain small, in order to avoid complying with labour regulation. Further, these laws only cover the organised sector (around 7% of the workforce).

- Thresholds for lay-off, closure and retrenchment: The Industrial Disputes Act (IDA) 1947, requires factories, mines and plantations employing 100 or more workers to obtain prior permission of the government before closing down, or laying off or retrenching workers. It has been argued that the requirement of prior permission has created an exit barrier for firms and hindered their ability to adjust labour workforce to production demands.

- Labour Administration: All labour laws have distinct compliance requirements for employing units. Multiplicity of labour laws has resulted in multiple inspections, returns and registers. One private study reported that states have 423 labour-related Acts, 31,605 compliances and 2,913 related filings. On the other hand, it has been argued that the labour enforcement machinery has been ineffective because of poor enforcement, inadequate penalties and rent-seeking behaviour of inspectors. Further, dispute resolution processes need reform to make them more effective.

- Contract Labour: It has been argued that labour compliances and economic considerations have resulted in increased use of contract labour. The share of contract workers in factories among total workers increased from 26% in 2004-05 to 36% in 2017-18, while the share of directly hired workers fell from 74% to 64% over the same period. This flexibility has come at a cost of increase vulnerability since contract labour have been denied basic protections (such as assured wages) and are not entitled to be regularized in cases where contract labour is prohibited by the government.

- Trade Unions: There are a large number of registered trade unions, including several within an establishment. There are no criteria to determine which unions can formally negotiate with the management. Settlements made with unions are only binding on the participating unions. This has affected collective bargaining rights of workers. Further, questions have been raised on the extent to which non-employees may be permitted in trade unions.

- Delegated Legislation: Under the Constitution, the legislature has the power to make laws and the government is responsible for implementing them. Often, the legislature enacts a law covering the general principles and policies, and delegates detailed rule-making to the government to allow for expediency and flexibility. However, certain functions and powers should not be delegated to the government. These include framing the legislative policy to determine the principles of the law. Any Rule should also remain within the scope of the delegating Act. The question is which matters should be retained by the legislature and which of these could be delegated to the government.

CODES

Code on Industrial Relations, 2020

- Exemption: The appropriate government may exempt any new industrial establishment or class of establishments from the provisions of the Code in public interest.

- Standing Orders: all industrial establishment with 300 workers or more must prepare standing orders on the matters listed in a Schedule to the Code. These matters relate to: (i) classification of workers, (ii) manner of informing workers about work hours, holidays, paydays, and wage rates, (iii) termination of employment, and (iv) grievance redressal mechanisms for workers.

- Prior permission of the government: an establishment having at least 300 workers was required to seek prior permission of the government before closure, lay-off, or retrenchment. Lay-off refers to an employer’s inability to continue giving employment to a worker in the face of adverse business conditions. Retrenchment refers to the termination of service of a worker for any reason other than disciplinary action.

- Powers to the central government to revise the threshold: government can only increase the threshold for the establishments to seek prior permission before closure, lay-off or retrenchment.

- Sole Negotiating Union: if there were more than one registered trade union of workers functioning in an establishment, the trade union having more than 51% of the workers as members would be recognised as the sole negotiating union.

- Negotiation Council: In case no trade union is eligible as sole negotiating union, a negotiating council will be formed consisting of representatives of unions that have at least 20% of the workers as members.

- Disputes relating to termination of individual worker: code classifies any dispute in relation to discharge, dismissal, retrenchment, or otherwise termination of the services of an individual worker to be an industrial dispute. The worker may apply to the Industrial Tribunal for adjudication of the dispute. The worker may apply to the Tribunal 45 days after the application for the conciliation of the dispute was made.

Code on Social Security, 2020

- Social security entitlements: central government may, by notification, apply the Code to any establishment (subject to size-threshold as may be notified).

- Social security funds for unorganised workers, gig workers and platform workers: central government will set up social security funds for unorganised workers, gig workers and platform workers. Further, state governments will also set up and administer separate social security funds for unorganised workers. Code also makes provisions for registration of all three categories of workers - unorganised workers, gig workers and platform workers.

- National Social Security for gig workers and platform workers: provides for the establishment of a national and various state-level boards for administering schemes for unorganised sector workers. In addition to unorganised workers, the National Social Security Board may also act as the Board for the purposes of welfare of gig workers and platform workers and can recommend and monitor schemes for gig workers and platform workers. In such cases, the Board will comprise of a different set of members including: (i) five representatives of aggregators, nominated by the central government, (ii) five representatives of gig workers and platform workers, nominated by the central government, (iii) Director General of the ESIC, and (iv) five representatives of state governments.

- Role of aggregators: code clarifies that schemes for gig workers and platform workers may be funded through a combination of contributions from the central government, state governments, and aggregators.

- Code changes the definitions of certain terms. These include: (i) expanding the definition of ‘employees’ to include workers employed through contractors, (ii) expanding the definition of “inter-state migrant workers” to include self-employed workers from another state, (iii) expanding the definition of “platform worker” to additional categories of services or activities as may be notified by the government, (iv) expanding the definition of audio-visual productions to include films, web-based serials, talk shows, reality shows and sports shows, and (v), exempting construction works from the ambit of “building or other construction work” if the total cost of construction work exceeds Rs 50 lakhs (and if they employ more than a certain notified number of workers).

- Term of eligibility for gratuity: educes the gratuity period from five years to three years for working journalists.

- Appeals: authorised officers were empowered to conduct inquiries and decide: (i) disputes regarding the applicability of the provisions of provident fund (PF) and employee state insurance (ESI) to certain establishments, and (ii) determine amounts due from employers under these heads. No provisions for review.

- Determination of escaped amounts: Under the 2019 Bill, after passing orders, the authorized officer could, within five years of the order, reopen any case and pass further orders to re-determine the amounts due from the employer if he had reason to believe that: (i) certain amounts had escaped his notice because of failure of the employer to disclose relevant documents/facts, or (ii) certain amounts had escaped his determination because of information received consequently. The 2020 Bill removes this provision.

- Offences and penalties: the maximum imprisonment for obstructing an inspector from performing his duty has been reduced from one year to six months. Similarly, the penalty for unlawfully deducting the employer’s contribution from the employee’s wages has been changed from imprisonment of one year or fine of Rs 50,000 to only fine of Rs 50,000.

- Composition of boards for unorganised workers: expands the representation of central government officials in the National Social Security Board for unorganised workers from five members to 10 members. Similarly, the number of state government officials in the state Boards for unorganised workers has been increased from seven to 10 members.

- Additional powers during an epidemic: the central government may defer or reduce the employer’s or employee’s contributions (under PF and ESI) for a period of up to three months in the case of a pandemic, endemic, or national disaster.

Code on Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions, 2020

- Exemption: empowers the state government to exempt any new factory from the provisions of the Code in order to create more economic activity and employment.

- Factory: defines a factory as any premises where manufacturing process is carried out and it employs more than: (i) 20 workers, if the process is carried out using power, or (ii) 40 workers, if it is carried out without using power.

- Establishments engaged in hazardous activity: defines an establishment as a place where any business, trade, or occupation is carried out regardless of the number of workers.

- Contract workers: Code will apply to establishments or contractors employing 50 or more workers (on any day in the last one year).

- Code prohibits contract labour in core activities, except where: (i) the normal functioning of the establishment is such that the activity is ordinarily done through contractor, (ii) the activities are such that they do not require full time workers for the major portion of the day, or (iii) there is a sudden increase in the volume work in the core activity which needs to be completed in a specified time. The appropriate government will decide whether an activity of the establishment is a core activity or not. However, the code defines a list of non-core activities where the prohibition would not apply. This includes a list of 11 works including: (i) sanitation workers, (ii) security services, and (iii) any activity of intermittent nature even if that constitutes a core activity of an establishment.

- Code will apply to contract labour engaged through a contractor in the offices of the central and state governments (where the respective government is the principal employer).

- Daily work hour limit: fixes the maximum limit at eight hours per day.

- Employment of women: provides that women will be entitled to be employed in all establishments for all types of work under the code It also provides that in case they are required to work in hazardous or dangerous operations, the government may require the employer to provide adequate safeguards prior to their employment.

- Inter-state migrant workers and unorganized workers: defines inter-state migrant worker as a person who: (i) has been recruited by an employer or contractor for working in another state, and (ii) draws wages within the maximum amount notified by the central government. Code adds that any person who moves on his own to another state and obtains employment there will also be considered an inter-state migrant worker. It also specifies that only those persons will be considered as inter-state migrants who are earning a maximum of Rs 18,000 per month, or such higher amount which the central government may notify.

- Benefits for inter-state migrant workers: provides for certain benefits for inter-state migrant workers. These include: (i) option to avail the benefits of the public distribution system either in the native state or the state of employment, (ii) availability of benefits available under the building and other construction cess fund in the state of employment, and (iii) insurance and provident fund benefits available to other workers in the same establishment.

- Database for inter-state migrant workers: requires the central and state governments to maintain or record the details of inter-state migrant workers in a portal. An inter-state migrant worker can register himself on the portal on the basis of self-declaration and Aadhaar.

- Social Security Fund: provides for the establishment of a Social Security Fund for the welfare of unorganised workers. The amount collected from certain penalties under the Code (including the amount collected through compounding) will be credited to the Fund. The government may prescribe other sources as well for transferring money to the Fund.

Code on Wages, 2019

- Coverage: The Code will apply to all employees. The central government will make wage-related decisions for employments such as railways, mines, and oil fields, among others. State governments will make decisions for all other employments.

- Floor wage: According to the Code, the central government will fix a floor wage, taking into account living standards of workers. Further, it may set different floor wages for different geographical areas. Before fixing the floor wage, the central government may obtain the advice of the Central Advisory Board and may consult with state governments.

- Fixing the minimum wage: The Code prohibits employers from paying wages less than the minimum wages. Minimum wages will be notified by the central or state governments. This will be based on time, or number of pieces produced. The minimum wages will be revised and reviewed by the central or state governments at an interval of not more than five years. While fixing minimum wages, the central or state governments may take into account factors such as: (i) skill of workers, and (ii) difficulty of work.

- Overtime: The central or state government may fix the number of hours that constitute a normal working day. In case employees work in excess of a normal working day, they will be entitled to overtime wage, which must be at least twice the normal rate of wages.

- Payment of wages: Wages will be paid in (i) coins, (ii) currency notes, (iii) by cheque, (iv) by crediting to the bank account, or (v) through electronic mode. The wage period will be fixed by the employer as either: (i) daily, (ii) weekly, (iii) fortnightly, or (iv) monthly.

- Deductions: Under the Code, an employee’s wages may be deducted on certain grounds including: (i) fines, (ii) absence from duty, (iii) accommodation given by the employer, or (iv) recovery of advances given to the employee, among others. These deductions should not exceed 50% of the employee’s total wage.

- Determination of bonus: All employees whose wages do not exceed a specific monthly amount, notified by the central or state government, will be entitled to an annual bonus. The bonus will be at least: (i) 8.33% of his wages, or (ii) Rs 100, whichever is higher. In addition, the employer will distribute a part of the gross profits amongst the employees. This will be distributed in proportion to the annual wages of an employee. An employee can receive a maximum bonus of 20% of his annual wages.

- Gender discrimination: The Code prohibits gender discrimination in matters related to wages and recruitment of employees for the same work or work of similar nature. Work of similar nature is defined as work for which the skill, effort, experience, and responsibility required are the same.

- Advisory boards: The central and state governments will constitute advisory boards. The Central Advisory Board will consist of: (i) employers, (ii) employees (in equal number as employers), (iii) independent persons, and (iv) five representatives of state governments. State Advisory Boards will consist of employers, employees, and independent persons. Further, one-third of the total members on both the central and state Boards will be women. The Boards will advise the respective governments on various issues including: (i) fixation of minimum wages, and (ii) increasing employment opportunities for women.

- Offences: The Code specifies penalties for offences committed by an employer, such as (i) paying less than the due wages, or (ii) for contravening any provision of the Code. Penalties vary depending on the nature of offence, with the maximum penalty being imprisonment for three months along with a fine of up to one lakh rupees.

BENEFITS OF THE LABOUR CODES

- Compulsory facility for Helpline for redressal of problems of migrant workers.

- Making a national database of migrant workers.

- Provision for accumulation of one day leave for every 20 days worked, when work has been done for 180 days instead of 240 days.

- Equality for women in every sphere : Women have to be permitted to work in every sector at night, but it has to be ensured that provision for their security is made by the employer and consent of women is taken before they work at night.

- In the event of death of a worker or injury to a worker due to an accident at his workplace, at least 50 % share of the penalty would be given. This amount would be in addition to Employees Compensation.

- Provision of “Social Security Fund” for 40 Crore unorganized workers along with GIG and platform workers and will help Universal Social Security coverage

- Pay parity to women workers as compared to their male counterparts.

- Occupational Safety & Health Code to also can now over cover workers from IT and Service Sector.

- 14 days-notice for Strike so that in this period amicable solution comes out.

- Vibrant mechanism proposed for speedier disposal by Labour Tribunals as “Justice delayed is Justice denied”.

- The Codes to Promote Harmonious Industrial Relations for higher productivity and more employment generation.

- Labour Codes to stablish transparent, answerable and simple mechanism reducing registration requirement to just one from eight; need of licence also to just one from three four under different laws earlier.

- Inspector to be now made as Inspector – cum- Facilitator and introduction of Random, Web Based Inspection System to remove to Inspector Raj.

- Penalties increase manifold; to act as deterrent.

ISSUES

Some common issues across the three Labour Bills:

- Definition of ‘appropriate government’: All three Labour Bills specify that the central government will act as the appropriate government for any central public sector undertaking (PSUs). The central government will continue to be the appropriate government for a central PSU even if the holding of the central government in that PSU becomes less than 50%. It is unclear as to why the central government should continue to exercise jurisdiction over an establishment in which it does not own controlling stake (even in cases where it has sold its entire stake)

- Delegated Legislation: Under the Constitution, the legislature has the power to make laws and the government is responsible for implementing them. Often, the legislature enacts a law covering the general principles and policies, and delegates detailed rule-making to the government to allow for expediency and flexibility. However, certain functions and powers should not be delegated to the government. These include framing the legislative policy to determine the principles of the law. Any Rule should also remain within the scope of the delegating Act. The three labour Bills delegate various essential aspects of the laws to the government through rule-making. These include: (i) increasing the threshold for lay-offs, retrenchment, and closure, (ii) setting thresholds for applicability of different social security schemes to establishments, and (iii) specifying safety standards, and working conditions to be provided by establishments under the occupational safety Code. The question is whether the power to decide such matters should be retained by the legislature or whether these could be delegated to with the government.

- Power to exempt establishments: Central and the state government have wide discretion in providing exemptions from these codes. Every factory would generate employment, and public interest could be interpreted broadly. The exemptions could cover a wide range of provisions including those related to hours of work, safety standards, retrenchment process, collective bargaining rights, contract labour.

- Question arises of the extent to which establishments should be covered by the codes. Low numeric thresholds may create adverse incentives for establishments sizes to remain small, in order to avoid complying with labour regulation. some have argued that basic provisions for enforcement of wages, provision of social security, safety at the workplace, and decent working conditions, should apply to all establishments, regardless of size.

Key Issues in the Industrial Relations Code, 2020:

- Strikes and lock-outs may become difficult for all establishments: code requires all persons to give a prior notice of 14 days before a strike or lock-out. This notice is valid for a maximum of 60 days. The Bill also prohibits strikes and lock-outs: (i) during and up to seven days after a conciliation proceeding, and (ii) during and up to sixty days after proceedings before a tribunal. This may impact the ability of workers to strike and employers to lock-out workers.

- Power to government to modify or reject tribunal awards: code provides for the constitution of Industrial Tribunals and a National Industrial Tribunal to decide disputes. It states that the awards passed by a Tribunal will be enforceable on the expiry of 30 days. However, the government can defer the enforcement of the award in certain circumstances on public grounds affecting national economy or social justice. The notification and the order will be tabled in the legislature. The question is whether such a provision would violate the principle of separation of powers between the executive and the judiciary, since it empowers the government to change the decision of the tribunal through executive action. Further, it raises the question of whether there is a conflict of interest, as the government may modify an award made by the Tribunal in a dispute in which it is a party.

- Provisions for formation of a negotiation council may be restrictive: It is unclear as to what will happen in case there are multiple registered trade unions which enjoy this support (of 10% of members) but no union has the required support of at least 20% workers to participate in the negotiating council.

- Provisions on fixed term employment: Fixed term employment may allow employers the flexibility to hire workers for a fixed duration and for work that may not be permanent in nature. Further, fixed term contracts are negotiated directly between the employer and employee and reduce the role of a middleman such as an agency or contractor. They may also benefit the worker since the Code entitles fixed term employees to the same benefits (such as medical insurance and pension) and conditions of work as are available to permanent employees. This could help improve the conditions of temporary workers in comparison with contract workers who may not be provided with such benefits. However, unequal bargaining powers between the worker and employer could affect the rights of such workers since the power to renew such contracts lies with the employer. This may result in job insecurity for the employee and may deter him from raising issues about unfair work practices, such as extended work hours, or denial of wages or leaves.

- Certain terms not defined in the Code: it does not define the terms ‘manager’ or ‘supervisor’ in this context. These terms are also used in the remaining three labour Codes, i.e., on Occupational Safety and Health, Wages and Social Security. Code does not define the term ‘contractor’, ‘establishment’.

Key Issues in the Code on Social Security, 2020:

- Purpose of the Bill: code continues to retain thresholds based on the size of establishment for making certain benefits mandatory. It also continues to treat employees within the same establishment differently based on the amount of wages earned. It also continues to retain the existing fragmented set up for the delivery of social security benefits.

- Provisions on gig workers and platforms workers are unclear: Consider the example of a driver working for an app-based taxi aggregator. Here, there is no employee-employer relationship. For example, appointment letters are not issued, social security benefits are absent, work hours are not regulated by the employer, and the driver may choose to work for a competitor taxi aggregator. Therefore, the nature of the work involved may lie outside the purview of a ‘traditional employer-employee relationship’, making him a ‘gig worker’. However, the driver is able to pursue this job only through an online platform. This would meet the definition of a ‘platform worker’ as well. Such a driver may also be an ‘unorganised worker’ as he may be self-employed. With such overlap across definitions, it is unclear how schemes specific to these categories of workers will apply.

- Provisions on gratuity for fixed term workers unclear

- Mandatory linking with Aadhaar may violate Supreme Court judgement

- Code defines the term ‘employer’ to mean a person who employs any persons and specifically includes certain categories of workers. In the case of a factory, employer means the occupier of a factory, i.e., the person with ultimate control over the affairs of the company. However, the remaining three labour codes define the term ‘employer’ to include occupier as well as the manager of the factory. It is not clear why managers of factories have not been included in the definition. Further, the code also does not define certain terms used to define an ‘establishment’. These include the terms ‘industry’, ‘trade’, ‘business’, ‘manufacture’ or ‘occupation’.

Key Issues in the Code on Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions, 2020:

- Rationale for some special provisions unclear: The Bill contains general provisions which apply to all establishments. These include provisions on registration, filing of returns, and duties of employers. However, it also includes additional provisions that apply to specific type of workers such as those in factories and mines, or as audio-visual workers, journalists, sales promotion employees, contract labour and construction workers. It may be argued that special provisions on health and safety are required for certain categories of hazard-prone establishments such as factories and mines. It may be necessary to allow only licensed establishments to operate factories and mines. Similarly, special provisions may be required for specific categories of vulnerable workers such as contract labour and migrant workers. However, the rationale for mandating special provisions for other workers is not clear. For example, the Bill requires that any person suffering from deafness or giddiness may not be employed in construction activity which involve a risk of accident. The question is why such a general safety requirement is not provided for all workers. Similarly, the Bill provides for registration of employment contracts for audio-visual workers, raising the question of why there is a special treatment for this category. The rationale for differential treatment with regard to working conditions between working journalists and sales promotion employees on the one hand, and all other workers on the other hand, is unclear.

- Civil Court barred from hearing matters under the Code

Changes and reforms in the labour laws have been conceptualized keeping in mind the changing scenario over the years and also making them futuristic so that country marches on faster growth trajectory. With these the peaceful and harmonious industrial relations will be promoted in the country which in turn will lead to growth of industry, employment, income, balanced regional development and will bring more disposal income in the hands of workers. These path breaking reforms in the country will help it to attract the Foreign Direct Investment and also domestic investment from the entrepreneurs and will end ‘inspector raj’ in the country and will bring total transparency in the system. India will become favourite investment destination in the world.