Description

Disclaimer: Copyright infringement not intended.

Context

- Recently, the Congress on Thursday halted its ‘Mekedatu march’, a day after the Karnataka High Court raised questions on how it was being carried out amid rising Covid-19 cases.

Mekedatu Balancing Reservoir Project

About

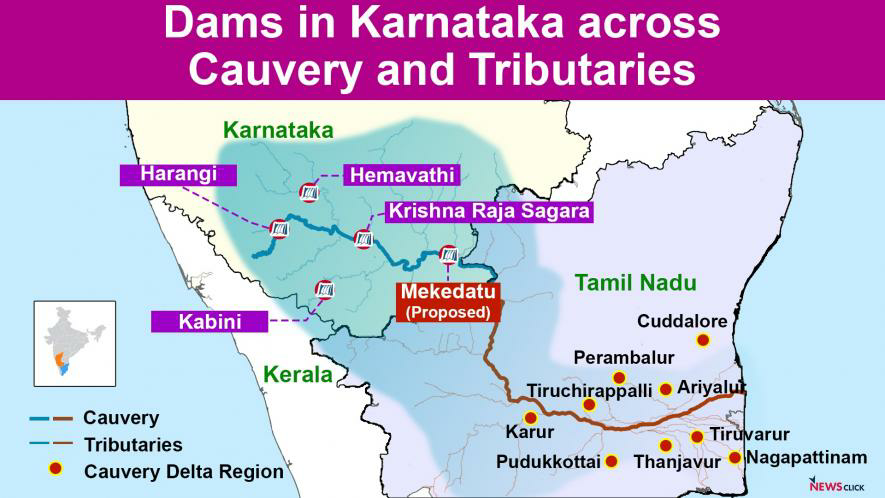

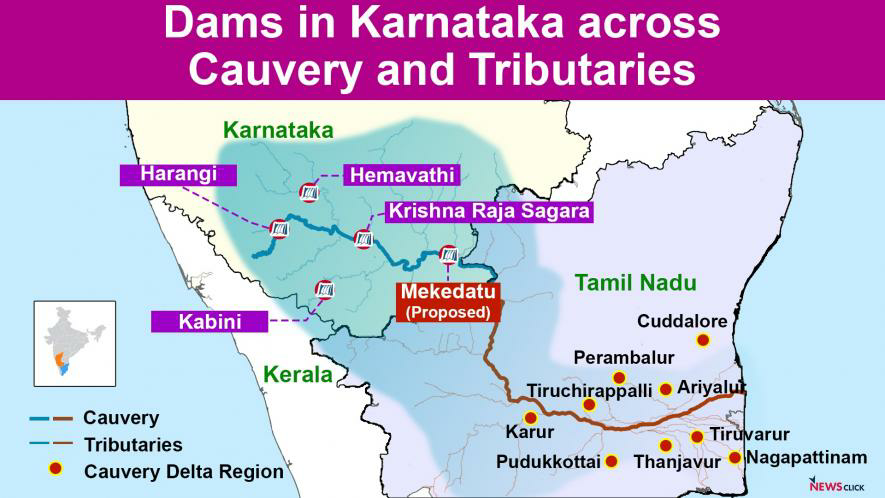

- Karnataka wants to construct a concrete gravity dam at Mekedatu with a storage capacity of 67.16 tmcft. The project was first announced in 2013.

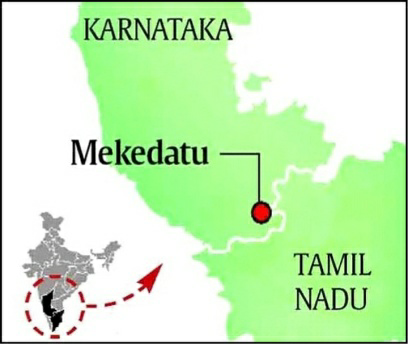

Location

- The project will actually come up at Ontigondlu, about 1.5 km from what is known as Mekedatu (literal meaning, goat's leap), at the confluence of Cauvery and Arkavathi rivers. It is about 90 km southwest of Bengaluru and 4 km from the Tamil Nadu border.

Objective

- It's primarily aimed at supplying 4.75 tmcf (thousand million cubic feet) of drinking water to Bengaluru and surrounding areas but will also generate 400 MW of hydroelectric power.

Project area

- The project requires a total of 5,252 hectares of land.Of the total land required, 3,181 hectares fall in the Cauvery Wildlife Sanctuary.

Current status of the project

- In January 2019, Karnataka submitted the Detailed Project Report (DPR) to the Central Water Commission (CWC) and later to the Cauvery Water Management Authority (CWMA) to get the consent of the co-basin states.

- The CWMA is yet to approve the DPR because Tamil Nadu, which is the co-basin state, has opposed the project.

- Tamil Nadu the lower riparian state has also approached the Supreme Court against Mekedatu, and the matter is pending adjudication.

- The project will need multiple clearances from the Centre and courts as it involves the Cauvery water sharing dispute.

Why is Tamil Nadu opposing Mekedatu

- Eat into the state’s share of Cauvery water: If the reservoir is constructed, Tamil Nadu fears, Karnataka will hoard water in the dam, thereby cheating it of its share of the Cauvery water.

- Violates Inter-State River Water Disputes Act: It has argued that as per the Inter-State River Water Disputes Act, Karnataka cannot build the dam without the consent of the lower riparian state, which is Tamil Nadu in this case.

Other hurdles to the project

- Environmental price: Green activists have questioned the environmental price of the project. A major chunk of the land that will be submerged by the dam will be of the Cauvery Wildlife Sanctuary area, which is a key elephant corridor.

- Threat to Endangered animals: The sanctuary is also home to many endangered wildlife species. The sanctuary also acts as a buffer area for wildlife animals such as tigers in the nearby Male Mahadeshwara Hills and Biligiriranga Hills.

- Man- Animal Conflict: Activists fear that the loss of this space will only lead to more man-animal conflict.

Karnataka's argument

- Within its rights: The Karnataka government has maintained that it is well within its rights to construct the dam as long as it makes sure that Tamil Nadu gets its annual share of water as prescribed by the Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal.

- No violation of Inter-State River Water Disputes Act: Since the dam will come up within Karnataka, the state is not violating any law.

- Redressal of water shortage issue: There is also an acute power shortage in Karnataka. The state sees Mekedatu as an opportunity to supply sufficient water to meet the ever-growing needs of Bengaluru and the surrounding districts.

- Boost to Tourism: The state also hopes that the dam will boost tourism in the area.

The recent ‘Mekedatu march’

- The ‘Mekedatu march’ had been launched for implementation of a project to build a reservoir on the Cauvery.

- The ‘Walk for Water’, March by Karnataka has been temporarily suspended due to rising Covid-19 cases.

River Cauvery

- Ancient name and Literature: It was also called as Ponni (the golden maid- as the Cauvery is sometimes called, in reference to the fine silt it deposits) in Tamil literature. Profusely described in the Tamil Sangam literature

- Source: Rises at Talakaveri in the Brahmagiri range in the Western Ghats, Kodagu district of the state of Karnataka.

- States flowing through: Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.

- Drains: It reaches the sea in Poompuhar in Mayiladuthurai district before its outfall into the Bay of Bengal.

- Size: It is the third largest river – after Godavari and Krishna – in southern India and the largest in the State of Tamil Nadu, which, on its course, bisects the state into North and South.

- Spiritual significance: The Kaveri is a sacred river to the people of South India and is worshipped as the Goddess Kaveriamma.

- Major Tributaries: Harangi, Hemavati, Kabini, Bhavani, Lakshmana Tirtha, Noyyal and Arkavati.

- Minor Tributaries: Three minor tributaries, Palar, Chinnar and Thoppar enter into the Kaveri on her course, above Stanley Reservoir in Mettur, where the dam has been constructed.

- Drainage Basin: The river basin covers three states and a Union Territory as follows: Tamil Nadu, 43,868 square kilometers; Karnataka, 34,273 square kilometres; Kerala, 2,866 square kilometres, and Puducherry, 148 square kilometers.

- Falls associated: In Chamarajanagar district, Karnataka, it forms the Shivanasamudra Falls. Upon entering Tamil Nadu, the Kaveri continues through a series of twisted wild gorges until it reaches Hogenakal Falls.

- Dams on it: Mettur Dam was constructed for irrigation and hydel power in Tamil Nadu.

- Islands Formed: Srirangapatna and Shivanasamudra.

|

Cauvery Water Dispute: A Timeline

The Cauvery water dispute is 122 years old.

Roots: Agreements of 1892 and 1924 between the then Kingdom of Mysore and the then Madras Presidency. Madras disagrees to Mysore administration’s proposal to build irrigation systems, arguing that it would impede water flow into Tamil Nadu.

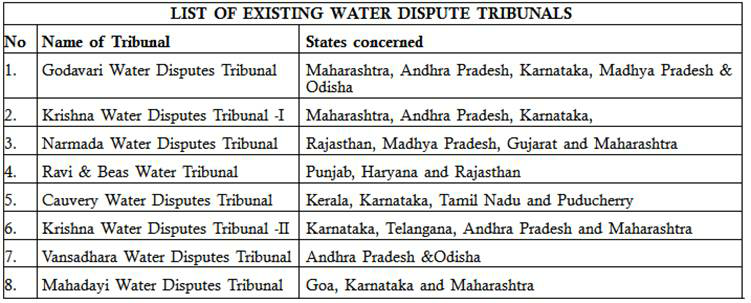

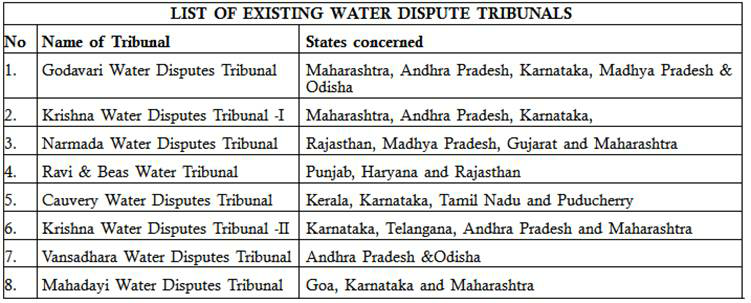

1990: A Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal (CWDT), set up under the centre after the Supreme Court’s direction.

2007: Tribunal delivered its final verdict on how water should be shared between Tamil Nadu, Karnataka Kerala and Puducherry. All states challenged the share assigned to them.

2012, 2016, 2017: Supreme Court Interventions and directions.

2018 SC final verdict: Karnataka will get 284.75 tmc ft, Tamil Nadu will get 404.25 tmc ft, Kerala will get 30 tmc ft and Puducherry will get 7 tmc ft, 10 tmc ft will be reserved for Environmental Protection and 4 tmc ft will be reserved for Inevitable Wastage into the Sea. Central government notified the ‘Cauvery Water Management Scheme’ as per SC’s direction constituting the ‘Cauvery Water Management Authority’ and the ‘Cauvery Water Regulation Committee’.

|

Interstate (River) Water Disputes

- Interstate (River) Water Disputes (ISWDs) are a continuing challenge to federal water governance in India.

- Rooted in constitutional, historico-geographical, and institutional ambiguities, they tend to become prolonged conflicts between the states that share river basins.

Subnational disputes are far more omnipresent, and are much more economically and socially disruptive in nature.

Constitutional Approach for Inter-state River water dispute

- Entry 17 of State List deals with water i.e. water supply, irrigation, canal, drainage, embankments, water storage and water power.

- Entry 56 of Union List empowers the Union Government for the regulation and development of inter-state rivers and river valleys to the extent declared by Parliament to be expedient in the public interest.

- Article 262:

In case of disputes relating to waters:

- Parliament may by law provide for the adjudication of any dispute or complaint with respect to the use, distribution or control of the waters of, or in, any inter-State river or river valley.

- Parliament may, by law provide that neither the Supreme Court nor any other court shall exercise jurisdiction in respect of any such dispute or complaint as mentioned above.

- Laws according to Article 262:

- River Board Act, 1956: The river Boards were supposed to advise on the inter-state basin to prepare development scheme and to prevent the emergence of conflicts. Till date, no river board as per above Act has been created.

- Inter-State Water Dispute Act, 1956: In case, if a particular state or states approach to Union Government for the constitution of the tribunal:

- Central Government should try to resolve the matter by consultation among the aggrieved states.

- In case, if it does not work, then it may constitute the tribunal.

Provisions of the Inter-State River Dispute (Amendment ) Act, 2019

- A dispute between two states will first go to a dispute resolution committee. In case of its failure, dispute will go to the permanent tribunal.

- A single Tribunal with different benches for all the river disputes.

- Maximum duration for a tribunal award is 6 years. 1.5 years for dispute resolution committee and 4.5 years for tribunal’s hearing and verdict.

- Tenure of Tribunal Members will be of 5 years or 70 years of age. Tribunal will consist of domain experts.

- Tribunal decisions are binding and have authority of Supreme Court order.

- It will require maintenance of basin database.

Major Impediments

- Institutional lacunae: led to a fractured landscape of interstate river water governance in India.

- Lack of political will

- Inadequate appreciation of the ecological and economic costs of such protracted conflict has constantly evaded a sustainable and holistic approach to this issue based on federal cooperation.

- Institutional ambiguity: Article 262 deters the highest judiciary from adjudicating interstate river water disputes but article 136 empowers the Supreme Court to hear appeals against the tribunals and also ensure implementation of the tribunal. This creates an institutional ambiguity regarding which body i.e. the tribunals or the Supreme Court is the ultimate adjudicatory power in the realm of interstate river water disputes in India.

Way Ahead

- Distress sharing formula: the Supreme Court has to get the states to agree on a practical distress sharing formula in a deficit season.

- Institutional mechanisms for implementing tribunal awards: The Supreme Court has to clear the questions of law about who and what kind of institutional mechanisms should be put in place for implementing tribunal awards.

- Interstate coordination: There is a huge vacuum with respect to institutional avenues and credible practices for interstate coordination. The solution lies in cooperation and coordination, not in conflict.

- Interstate governance mechanisms: Creation of enduring and effective interstate governance mechanisms is the key to manage interstate water disputes.

- Conservation: Ecological restoration and conservation of aquatic biodiversity, in addition to the balancing of water supply and demand for human use in the management objectives and outcomes of the basin plan.

- Address River Basin issues: The identification of key issues and risks to river basins and the strategies needed to address them in both the short and long term.

- Consensus building: Consensus-building, based on sustained political deliberation. An example of such a consensus-based model, in which the Centre and the states have found an amicable way to coordinate, is the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST). The Centre brought the states on board to negotiate the reform in the spirit of “cooperative federalism.

- Complete Depoliticisation: Formulating an alternative to political negotiation is the only long-term and durable solution to river water conflicts, with a political will that can forge an amicable consensus for mutually agreed river-water sharing.

- Positive Politicisation: The issue in question and the demand for a solution must be highly politicised to ensure that the dispute gets adequate public attention and, consequently, electoral priority. A case in point is the 2012 mass-based anti-corruption movement in India, which relied on the extreme politicisation of the issue of corruption and the subsequent passing of the anti-corruption legislation – The Lokpal and Lokayuktas Act, 2013. Such “positive politicisation” of an issue can pave the way for concrete political action for conflict resolution.

- Need for clarity: Any concrete step towards a more responsive and effective river water governance mechanism, despite its well-meaning intent, would remain chequered unless deep-rooted Institutional ambiguities regarding the issue are constantly comprehended, recognised and interrogated in a bipartisan manner. (In ref to Art. 262 and Art. 136)

Final Thought

- The current condition of interstate river water governance in India warrants a new approach for cooperative federalism and interstate water governance.

https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-politics-and-controversies-around-proposed-dam-on-cauvery-7723390/