Description

Disclaimer: Copyright infringement not intended.

Context

- Central and State Governements are tussling over centralized Market-Based Economic Dispatch (MBED) mechanism.

Background

- Electricity distribution companies (discoms) in India predominantly buy electricity from the wholesale power market under long-term (typically 25 years), medium-term (up to 5 years), and short-term (up to 1 year) contracts.

- A majority of their daily power demand is met through long-and-medium-term contracts, while the rest is met through bilateral transactions between discoms via traders or power exchanges1, 2.

- Though a discom buys capacity through contracts of varying durations, it schedules power supply only on a day-ahead basis. To balance possible mismatches between procurement and supply, the discom either buys additional power from the market or other discoms (if the demand is expected to increase) or sells or curtails the excess contracted capacity (if the demand is expected to decrease)3.

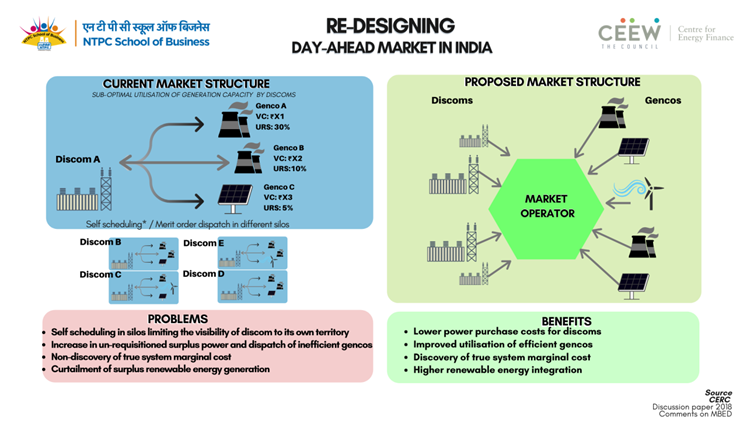

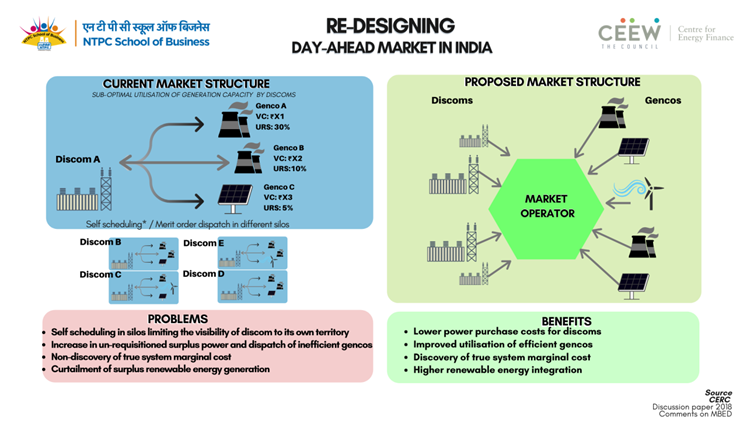

- In the current mechanism, power generators (gencos) supply power to the discoms as per their contracts. The discoms schedule power based on their demand estimate and the available capacity for each 15-minute time block for the day ahead. This is called ‘self-scheduling’. However, demand and supply can fluctuate unexpectedly and across time blocks.

- To handle such real-time imbalances between demand and supply, mechanisms such as rescheduling, deviation settlement, and ancillary services are deployed.

- Each of the 70+ discoms in the country schedule their required power with their respective contracted gencos. However, discoms are not obligated to disclose the cost (specifically, the variable cost) of their scheduled generation to the system operator. Interestingly, though there may be a genco offering its excess capacity at relatively low prices, this cheaper power may go underutilised as discoms are unaware of this availability. Given the financial distress of discoms, it is critical that we reduce such systemic inefficiencies.

- In December 2018, the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC) published a discussion paper Market-based Economic Dispatch of Electricity: Re-Designing of Day-ahead Market (Dam) In India.

- The paper proposes a day-ahead market where discoms and gencos can make demand and supply bids based on variable costs to a centralised platform mediated by a market operator (power exchange). The objective is to dispatch the power that costs the least first by giving discoms the ability to source power from all gencos, as long as grid security is maintained.

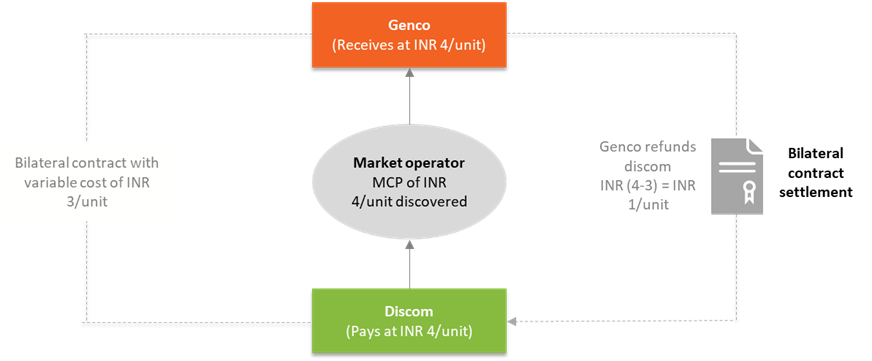

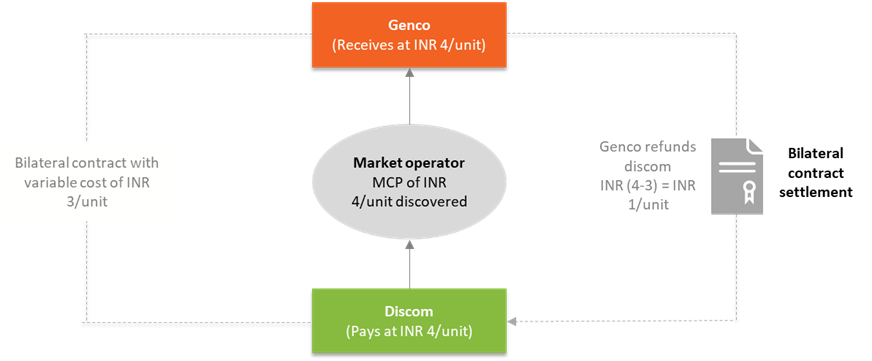

- The market operator will arrive at a market clearing price (MCP) by matching the last generators’ supply offer matched to meet the demand offers. The discoms would have to procure the required electricity from the market operator at the MCP, which, in turn, would be paid to the gencos supplying power.

- The settlement for fixed costs shall be outside the ambit of this market. Discoms shall pay the same to their contracted gencos based on the latter’s availability. However, if the MCP is higher than the contracted price (variable cost) a genco had agreed with a discom, then the genco will refund the excess to the discom.

- This ensures that the discom will not be forced to pay more for its contracted capacity.

- This mechanism, referred to as ‘bilateral contract settlement’, shall be applicable in cases where a bilateral contract already exists between a genco and a discom to ensure price hedging for the latter. A sample transaction has been explained below.

MBED

- The MBED proposes a centralized scheduling model for dispatching India’s total annual electricity consumption of ~1,400 billion units. This is in line with the Centre’s ‘One Nation, One Grid, One Frequency, One Price’ formula.

- These remain inconsistent given power is a concurrent subject, with the right to legislation shared by both the Centre and the states.

- Power dispatch, too, is premised on a decentralized model for the last so many years, reinforced by the Electricity Act 2003 and the subsequent reforms. The proposed MBED effectively challenges the legislative powers of the states.

Relevance and impact

The proposed market design is expected to have the following impact on the power sector:

Reduced power purchase costs

- With a centralised pool of generation and demand offers, gencos will be forced to become more cost-efficient or shut down, thus lowering the overall variable cost of power in India.

Greater renewable energy integration

- With power being scheduled and dispatched over a larger balancing zone, renewable energy is expected to be curtailed at a lower rate.

Concerns

- The centralised nature of the mechanism challenges the provisions of the Electricity Act 2003, and the Indian Contract Act, 1872.

- Greater clarity is also needed on the legality of the proposed Bilateral Contract Settlement (BCS) mechanism under the scheme for refunding the difference between the Market Clearing Price and the contract price to keep intact the PPA prices.

|

India has a diversified electricity market ranging from long-term power purchase agreements (PPAs), cross border PPAs, short and medium term bilaterals, day-ahead power exchange, and a real-time online market. A major percentage of the installed power capacity –over 87 per cent – is tied up under long term PPAs of around 25 years. The remaining 13 per cent is transacted in the power markets, with nearly half of this over the power exchanges and the remaining through short-term and medium-term bilateral deals. At present, each control area or state follows merit-order dispatch (cheapest power dispatched first) from the basket of intra-state and inter-state resources and buys or sells on the day-ahead power exchange.

|

- The MBED model is seen as impinging on the relative autonomy of states in managing their electricity sector, including their own generating stations, and making the discoms (distribution companies that are mostly state-owned) entirely dependent on the centralized mandatory market pool requirements.

- There are concerns this could strip states of their freedom to decide their own electricity requirement while managing seasonal and local demand trends.

- The mechanism is expected to weaken market competition, thus stifling efficiency and innovation in the process.

- This also goes against the requirements of the emerging market trends with the increasing penetration of renewable energy and electric vehicles that will require decentralized markets and voluntary pools for effective functioning.

Way Ahead

- Instead of moving towards complete centralization, steps to reinforce the existing voluntary pool-based markets must be considered.

- An appropriate regulatory framework may be created for discoms and gencos to schedule transactions through the market.

- The states can be encouraged to offer their power in the open market on a ‘voluntary’ basis, bringing in additional capacity to the markets and increasing liquidity. This will help India move away from long-term PPAs, deepen power markets, and enhance efficiency/flexibility.

https://indianexpress.com/article/india/centre-states-tussle-over-a-centralised-market-for-electricity-8159047/