Description

GS PAPER III: Challenges to internal security through communication networks, role of media and social networking sites in internal security challenges, basics of cyber security; money-laundering and its prevention.

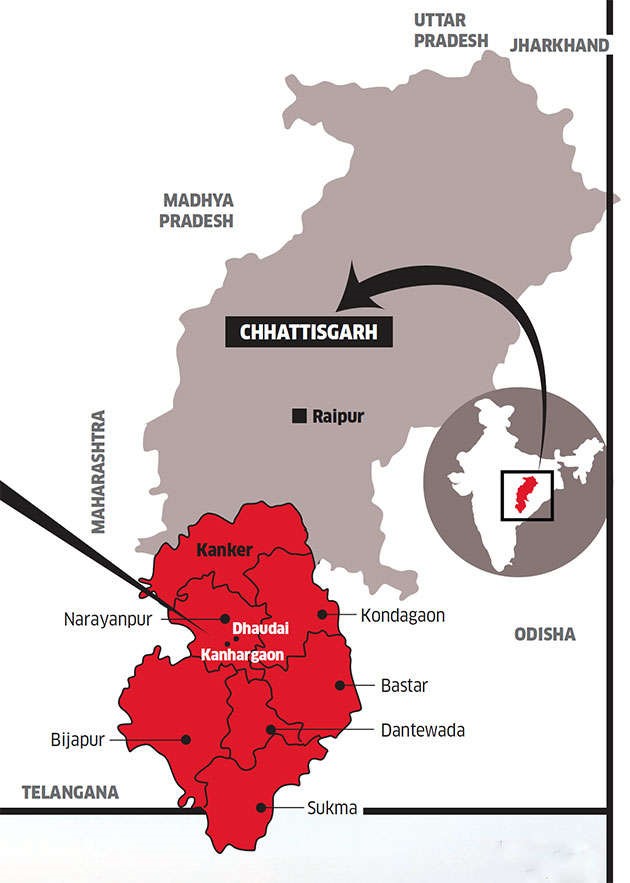

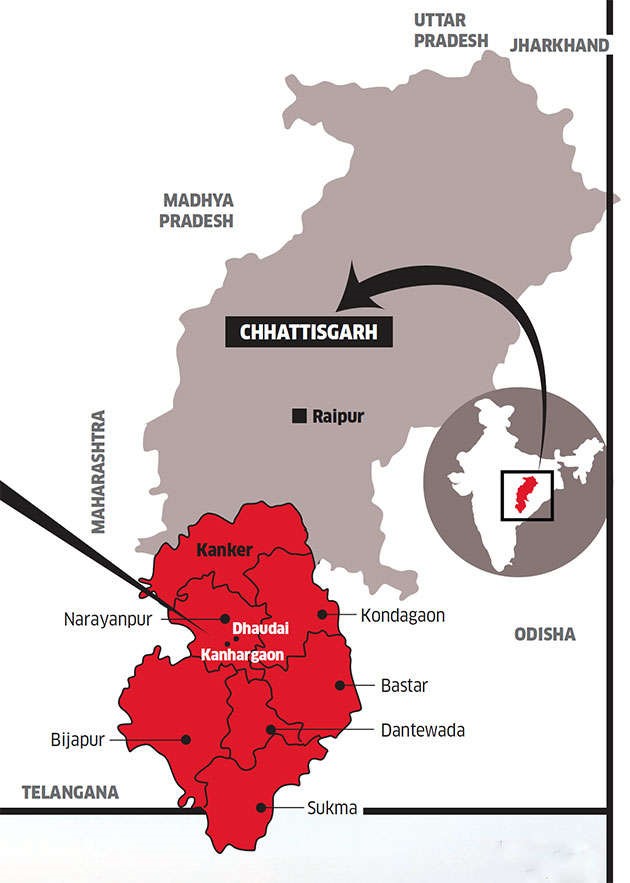

Context: On April 3, as 22 security force personnel fell to Maoist bullets in Bijapur, questions were raised not just on possible tactical mistakes by the forces but also on Chhattisgarh’s continued struggle in driving out Maoists from what is arguably their last bastion.

- Since the 2010 Chintalnar massacre that claimed 76 lives, the Dantewada-Sukma-Bijapur axis has claimed the lives of more than 175 security personnel in Maoist ambushes alone.

- Since a crackdown on Maoists starting 2005 in Left Wing Extremism (LWE) states, other states have largely tackled the problem.

- The number of districts declared Naxal-affected is now just 90, down from over 200 in the early 2000s. Yet Chhattisgarh struggles.

State police role is key

- Many have argued that Maoism has been defeated only in states where the state police have taken the lead.

- In Maharashtra, where Maoists held sway over several districts, they have now been confined to border areas of Gadchiroli thanks to local police and the C60 force.

- West Bengal achieved normalcy through an ingenious strategy adopted by the state police.

- The Jharkhand Jaguars have gained an upper hand in the past few years, and Odisha has confined Maoist activity largely to Malkangiri thanks to broad administrative interventions in Koraput.

- Central forces have the numbers and the training, but they have no local knowledge or intelligence.

- Only local police can drive out Maoists.

- The reason we are not succeeding in Chhattisgarh is because the local police have not yet taken the leadership position, although things have improved over the years.

Greatest internal security threat

- The Centre formally recognised the gravity of Maoist violence in 2004 when then PM Manmohan Singh called it the “greatest internal security threat for the country”.

- The Centre opened up purse strings for modernisation of state police forces, among various moves.

- When Maoist violence began in the 1980s, the Andhra police were poorly trained, inadequately funded and with no intelligence as public support was with the Maoists.

- Given that the Maoist movement initially had only landlords at its target, the state was late to react and after several setbacks to police, the state realised the importance of capacity building and “Work began on the principle of Defend, Destroy, Defeat and Deny.

- In 1989, the Greyhound were formed. It carried out intelligence-based operations against Maoists, while police and paramilitary personnel were pushed to hold and re-establish the rule of law in the areas cleared.

- This was coupled with a focus on development. A department called Remote and Interior Area Development Department was set up.

- The SP of the region was made an integral part of the Development Board to take decisions on roads etc. When all administrative wings become focused on one job, the punch of the government becomes mightier.

West Bengal

- West Bengal, the cradle of Naxalism, had stamped out Maoism in early 1970s, but it came back by the late 1990s, when Maoists began targeting CPM cadre in some districts.

- Maoists were eventually driven out by state police with robust use of technology and intelligence.

Odisha & Maharashtra

- There was a time in Odisha during the early 2000s when armouries of police stations in Koraput and Malkangiri were kept empty for fear of raids by Maoists.

- Thanks to rapid infrastructure development, particularly roads in Koraput, and killing of key Maoist leaders, Odisha police have confined Maoist activity to parts of Koraput and Malkangiri.

- Police have raised a force called the Special Operations Group to fight Maoists. However, due to proximity with Chhattisgarh, some trouble continues.

- Its elite commando force to fight Naxals, the C60, was raised back in 1991, and trained by the National Security Guards and at the Jungle Warfare Academy in Mizoram.

Bihar & Jharkhand

- The two states continue to have Maoist trouble in some districts, but violence has been going down.

- Jharkhand Jaguars have coordinated well with the central forces and together they have restricted the movement of Maoist leaders and cadres.

The Chhattisgarh challenge

- Trouble in Chhattisgarh started after Maoists began to be smoked out of Andhra Pradesh in the early 2000s.

- It was also the time when the Maoist movement went through a transformation of being a struggle against a class enemy (landlords) to a tribal movement against the state.

- It was also a different kind of challenge since Maoists had made strongholds in areas that had not even been mapped, let alone be administered.

- Between 2018 and 2020, Chhattisgarh has accounted for 45% of all incidents in the country and 70% of security personnel deaths in such incidents.

- Chhattisgarh is a different challenge. The terrain and demography is different from Andhra.

- Public have more sympathy for the Maoists

- Salwa Judum turned out to be counter-productive and information sources dried up after that.

- Also, the enemy strength is huge in Chhattisgarh.”

- The Chhattisgarh police too have raised a special counter-Maoist force, called District Reserve Guards (DRG).

- It is, however, relatively new and constituted differently than the Greyhounds.

- It has tribal recruits from Bastar and employs surrendered Maoists too.

- It has its advantages vis-à-vis local knowledge and intelligence gathering.

https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/fighting-left-wing-extremism-in-chhattisgarh-elsewhere-maoist-attack-crpf-7260456/