Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: THE HINDU

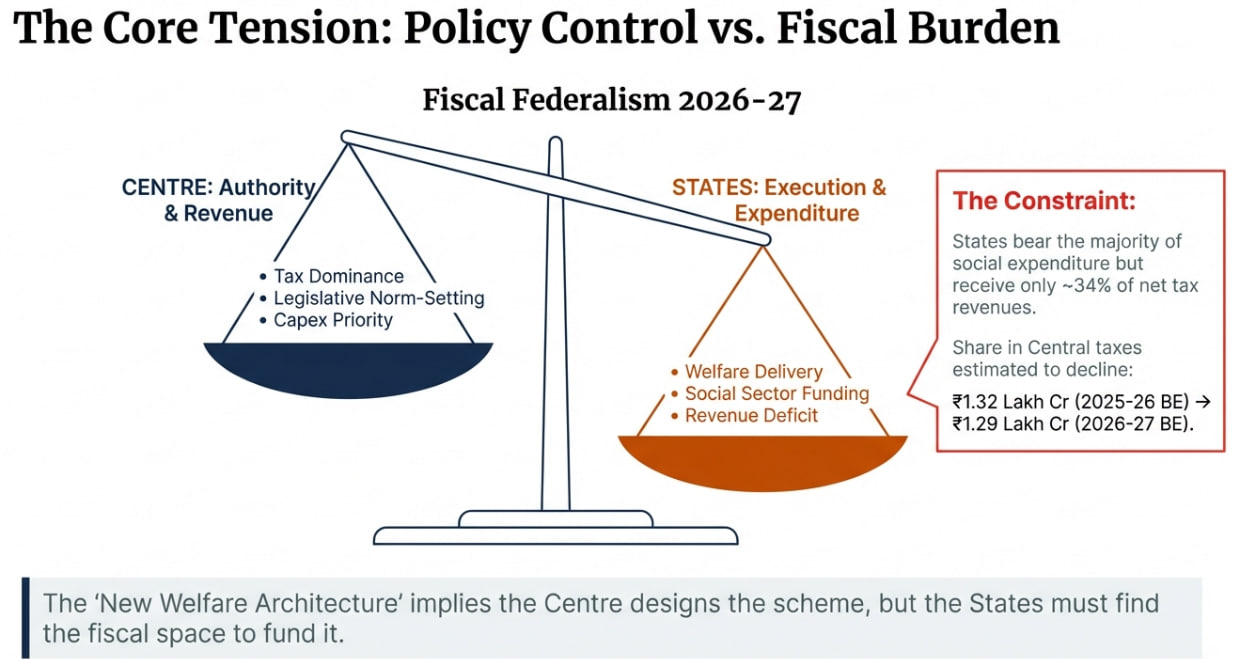

The increasing transfer of financial responsibility for social sector schemes to State governments strains fiscal federalism and raises doubts about the long-term viability of welfare delivery in India.

|

Read all about: Union Budget 2026 l 16th Finance Commission Report |

Fiscal Federalism refers to the division of financial powers, responsibilities, and resources between different levels of government (Union, State, and Local).

It is a critical component of India's quasi-federal structure, designed to ensure efficient public service delivery, promote regional equity, and maintain macroeconomic stability.

Its foundation lies in the Constitution of India, particularly in Articles 268 to 281 and the distribution of taxation powers in the 7th Schedule.

Key Instruments of Fiscal Federalism

Tax Sharing

The Constitution mandates the sharing of certain taxes collected by the Union government with the States. The Finance Commission (a constitutional body under Article 280) recommends the formula for this vertical (Centre to States) and horizontal (among States) distribution.

Grants-in-Aid

The Centre provides various grants to States to supplement their resources, address specific needs, or incentivize performance. These can be statutory, discretionary, or tied to specific schemes.

Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS)

These are programs funded jointly by the Centre and States but are largely designed and mandated by the Union government. States are responsible for their implementation.

State Borrowing

The Constitution lays down provisions for borrowing by the Centre and the States. State borrowing is subject to limits and conditions, often linked to the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act norms.

Shrinking the Divisible Pool: Cesses and Surcharges

The Issue: The Union government increasingly uses cesses and surcharges on taxes (e.g., income and corporation tax).

Impact on States: Revenue from cesses and surcharges is not part of the divisible pool of taxes and does not have to be shared with the states. This reduces the overall quantum of funds transferred to states as per the Finance Commission's recommendations.

The Goods and Services Tax (GST) Regime

The Goods and Services Tax (GST) Regime

Reduced Autonomy

With the implementation of GST, states have lost their power to set tax rates on a wide range of goods and services and are now dependent on the decisions of the GST Council, where the Union government holds influence.

Compensation Issues

The five-year promise to compensate states for revenue shortfalls has ended, leaving many states financially vulnerable as their revenue growth has not yet stabilized.

Conditionalities and Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS)

Increased Conditionalities

Much of central funding is conditional (CSS) or scheme-based, restricting states' ability to spend on their specific local priorities.

Unfunded Mandates

Inadequate financial support for mandated central policies forces states to merely implement them, straining their budgets and eroding their autonomy as governing units.

Constraints on State Borrowing

FRBM Limits

The Centre sets the net borrowing ceiling for states as a percentage of their GSDP, which, while promoting fiscal discipline, can restrict states from making crucial capital investments, especially during economic downturns.

Debt Servicing

High loan interest rates and rising debt are draining state revenues, which reduces the funds available for development and welfare.

Social Sector (Health & Education)

Cuts in funding for state-run hospitals, primary health centres (PHCs), and public schools.

Reduced ability to hire teachers, doctors, and healthcare workers.

Increased out-of-pocket expenditure for citizens on essential services.

Infrastructure & Economic Growth

Stalling or abandonment of state-led infrastructure projects like roads, irrigation, and urban transport.

Negative impact on job creation and economic activity.

Reduced investor confidence in state-level projects.

Governance & Accountability

Erosion of state autonomy to design policies tailored to local needs.

Weakens the accountability of state governments to their citizens, as they have limited control over expenditure.

Widens the development gap between financially stronger and weaker states.

Stagnant Allocations & Under-execution

Stagnant Allocations in Real Terms: While there are nominal increases, they fail to match inflation, leading to a real-term decline in resources for vulnerable populations.

Persistent Underspending: A systemic issue is the gap between Budget Estimates (BE) and Revised Estimates (RE), indicating poor execution and absorption capacity at the central level.

Prioritizing Capital over Human Development

The Capex Push: The allocation of over ₹12 lakh crore for capex is driven by the theory that infrastructure development will create a 'trickle-down' effect, boosting growth and crowding in private investment.

Unaddressed Economic Gaps: This focus overlooks fundamental challenges that require direct social investment, such as:

Mechanisms for Shifting the Welfare Burden

Reformed Cost-Sharing Norms: Since 2015, the cost-sharing ratios for most Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS) have been revised, compelling states to contribute a larger share of funds.

Restructuring of Schemes: The repealing of MGNREGA and its replacement with a new scheme, VB-G RAM G, with a 60:40 Centre-State cost-sharing ratio for its ₹96,000 crore allocation, exemplifies this shift. States are now legally mandated to provide 40% of the funds for a central-level legislation.

Mandate without Money: The Centre retains legislative and normative control, dictating the 'what' and 'how' of welfare, while states are left to manage a larger portion of the 'who pays'.

Rising Fiscal Stress on States

Shrinking Divisible Tax Pool: The states' actual share in total central tax revenue is around 34%, lower than the 41% recommended by the Finance Commission, because of the Centre's increasing reliance on cesses and surcharges, which are not shared with the states.

Declining Central Grants: Finance Commission grants to states are projected to decline from ₹1,32,767 crore (2025-26 BE) to ₹1,29,397 crore (2026-27 BE), further squeezing state finances.

The 'Unfunded Mandate' Dilemma: States are caught between their own developmental priorities and the legal obligation to fund centrally designed schemes with diminishing central financial support.

Decentralized Welfare: A Two-Sided Coin

|

Potential Benefits (Pros) |

Significant Risks (Cons) |

|

Tailored Solutions: States can design programs better suited to local needs. Local Accountability: May lead to better monitoring and ownership. Fosters Innovation: Encourages states to experiment with new welfare models. |

Widening Regional Disparities: Fiscally weaker states may struggle, increasing inequality. Dilution of Universal Rights: The principle of universal access to services could be compromised. Fiscal Strain on States: May lead to higher state debt or cuts in other critical sectors. Accountability Ambiguity: Blurring lines of responsibility for scheme failures. |

Rationalize CSS: Centrally Sponsored Schemes should be restructured into flexible block grants, giving states more freedom to design and implement programs based on local needs.

Strengthen the Finance Commission: The commission's independence must be protected, and its Terms of Reference (ToR) should be framed in consultation with states to ensure fairness and equity in devolution.

Revisit the GST Structure: Key reforms could include bringing excluded items (like petroleum) under GST and establishing a more robust mechanism for dispute resolution within the GST Council.

Enhance State Revenue Sources: There is a need to explore ways to empower states to augment their own revenue streams, such as through reforms in property tax or other local taxes.

Institutionalize Dialogue: Creating a platform for regular and structured dialogue between the Union and States, such as by strengthening the Inter-State Council, can help build trust and resolve disputes amicably.

A resilient and equitable fiscal federalism, evolving the Centre-State relationship into a genuine partnership, is a prerequisite for India's sustained economic growth, national unity, and inclusive development, deepening democracy through strengthened state fiscal capacity.

Source: THE HINDU

|

PRACTICE QUESTION Q. "Fiscal federalism in India is witnessing a centralization of policy and a decentralization of expenditure." Discuss. 150 words |

"Budgetary Illusion" refers to a phenomenon where the government announces high funding allocations in the Budget Estimates (BE) to signal support for a sector, but actual spending (Revised Estimates or RE) ends up being lower due to underutilization or cuts during the fiscal year.

Under Article 270 of the Constitution, cesses and surcharges levied by the Centre are excluded from the "Divisible Pool" of taxes. This means the Centre keeps 100% of this revenue, reducing the effective share of taxes that States receive, despite the Finance Commission recommending a 41% devolution.

VB-G RAM G is a new framework introduced to replace or restructure demand-based schemes like MGNREGA. It changes the fiscal responsibility, making Central funding contingent on States first contributing their share.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved