Disclaimer: Copyright infringement not intended.

Context

- President of the United Nations General Assembly and Maldives foreign minister Abdulla Shahid stressed on the role played by India at the UN.

- Acknowledging the pivotal role India played during the Covid recovery phase, the Maldivian leader underscored that the country had proven to be the “pharmacy of the world” that assisted several countries in the remotest parts of the globe.

India-Pharmacy of the World

- For over two decades, India has acquired the reputation of being the “pharmacy of the world” as its strong generic pharmaceutical industry has been supplying affordable medicines conforming to quality standards to the global markets.

- This reputation grew out of the critical interventions that the Indian companies had made during the HIV/AIDS pandemic, by supplying affordable antiretroviral medicines to African countries, when the major pharmaceutical producers had demanded excessively high prices for these medicines.

- Subsequently, after the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria became a reality as a multi-stakeholder initiative to reduce the burden of these diseases, the India’s generic industry emerged as one of the largest suppliers.

- Also significant is that fact that exports of medicines from India, which were around a billion dollars at the turn of the century, are currently well over $20 billion.

India’s Vaccine Diplomacy strategy during the pandemic

- In keeping with its historical role as a provider of affordable medicines, India has taken two significant initiatives to overcome the scourge of the COVID-pandemic.

- The first is to make vaccines widely available, which is in response to the growing evidence of the criticality of making COVID-19 vaccines accessible to all. The second initiative is a joint proposal tabled along with South Africa in the World Trade Organization (WTO), which seeks temporary waiver from the implementation and enforcement of four forms of intellectual property rights (IPRs). The objective is to ensure that COVID-19 vaccines, medicines and other medical products are freed from the encumbrances of these IPRs, thus making them affordable. The twin initiatives underline a key message for the global community: in pandemic times, medical products must be treated as global public goods.

- India has now emerged as one of the major suppliers of COVID-19 vaccines. The country is able to play this role given its partnership with the Serum Institute of India (SII), the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer by number of doses (the company claims it can produce 1.5 billion doses annually). In June 2020, SII entered into a licensing agreement with AstraZeneca, a British-Swedish pharmaceutical company, to supply one billion doses of the Oxford University COVID vaccine to middle and low income countries, including India. SII is currently supplying its vaccine, “Covishield”, to the Government of India. Prior to this tie-up, another India biopharmaceutical company, Bharat Biotech International Ltd together with the Indian Council of Medical Research, the government agency promoting biomedical research, began their collaboration developing a COVID vaccine, “Covaxin”.

- Even as it was organizing its COVID-vaccine roll-out, the Indian government announced an elaborate “vaccine diplomacy” strategy for providing vaccines to most of its neighbors, and a sizeable number of other developing countries, including those from Africa.

- In early 2021, India—driven by its ‘Neighbourhood First’ policy and in its understanding of its role as the ‘net security provider’ of the region- began providing COVID-19 vaccines on a priority basis to its immediate neighbours. India’s seven neighbors in South Asia: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Maldives, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.

- Other countries that have already received “vaccine assistance” are Seychelles, Myanmar and Mauritius. In the South Asian region in which China’s growing presence has been clearly discernible over the past few years, the Government of India’s “vaccine diplomacy” could help in making the playing field more even.

- India has decided to supply 10 million doses of the vaccine to Africa and 1 million to UN health workers India under the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) facility of the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations (GAVI).

- Several other countries, including Bahrain, Barbados, Dominica, Oman, are also part of India’s “vaccine assistance” program. Thus, India is using its soft power to assist developing countries, a role that it has increasingly been playing as a development partner.

Development Partnership Initiative

- Vaccine supplies to the various countries should be seen as a part of the development partnership initiative that the Government of India has been pursuing since the early 1950s. This initiative was formalized in 2012 with the establishment of the “Development Partnership Administration”, which, while extending support to other developing countries, recognizes that the “most fundamental principle in cooperation is respecting development partners and be guided by their development priorities”.

- Essentially, India’s development partnership is geared towards meeting the identified needs of the partner countries as is technically and financially feasible. In other words, India has been pursuing a “demand driven” development cooperation program and is, therefore, better suited to meet the requirements of the recipients.

Commercial terms for upper middle countries

- Another important aspect of India as a supplier of COVID-19 vaccines is that the government allowed vaccine exports on commercial terms, mostly to upper middle income countries seeking them, even when an embargo was imposed on commercial sales of vaccines in India.

- Morocco, Brazil and South Africa are among the countries that would benefit from this policy stance. Morocco is the largest importer of vaccines from India (6 million doses), while Brazil and South Africa have imported 2 million doses import 1 million doses of “Covishield” respectively.

Normalcy in India-Canada relations due to Vaccine Diplomacy

- The real value of India’s “vaccine diplomacy” was seen when Canadian Prime Minister, Trudeau, sought Prime Minister Modi’s assistance for vaccine supplies from SII. Over the past few months, relations between the two countries had soured, and therefore India’s “vaccine diplomacy” helped bring normalcy.

- Although Canada had firmed up deals with seven vaccine suppliers, timely supplies have severely impacted its vaccine roll-out plans. Supplies from SII will help Canada make up for the shortfall in its vaccine supplies.

India’s Vaccine sharing Policy amid Vaccine Nationalism

- The Indian government’s vaccine sharing policy with partner countries is without doubt a standout in times of the alarming precedent of “vaccine nationalism” practiced by several countries, instead of recognizing vaccines as global public good. A group of advanced countries, accounting for only 16 percent of the world’s population, have secured for themselves 60 percent of the global vaccine supplies.

- Canada heads the list of “vaccine nationalists,” having assured vaccine supplies that are nine times its population, while the United Kingdom has stocked enough doses to vaccinate every citizen six times. O

- ther countries to secure vaccine supplies that are well beyond their domestic requirements are Australia, Chile, the United States, and members of the European Union.

- On the other hand, India is sharing its available vaccine supplies with several countries, and also ensuring that the domestic demand is met.

- India’s Covishield vaccine, manufactured by ‘Serum Institute of India’ (SII), was delivered to all the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) countries under the ‘Vaccine Maitri’ initiative except Pakistan.

Health Diplomacy

- The concept of Global Health (Vaccine) Diplomacy has emerged as a cornerstone for foreign policies of major countries during the Pandemic. Although health diplomacy remained an important part of the major powers or countries’ foreign policies, it has become an important element in a global health crisis.

- With India as a pharmaceutical hub and ambitions for regional and global leadership, the GHD has emerged as an integral part of Indian foreign policy in general and in the form of the ‘Neighborhood First’ policy in particular.

According to WHO, the main goals of health diplomacy are

(1) to ensure better health security and population health;

(2) to improve relations between states;

(3) to commit to improving health through the involvement of a wide range of actors; and

(4) to achieve outcomes that support the goals of reducing poverty and increasing equity.

- GHD holds some promise of enabling ‘policy coherence’ through the determinants of health and human security to ensure that health is seen as a global public good.

- In this context, scholars have witnessed GHD’s role in the formulation of International Health Regulations (IHRs), 2005, Framework Convention of Tobacco Control, Universal Health Coverage (Sustainable Developmental Goals, UN Climate Change Conference 2019; UN, 2019 and most recently the COVAX Facility in 2020.

- Researchers have emphasized the critical role of GHD in promoting peace, improving health and well-being, strengthening global leadership and international cooperation, global coordination, negotiating for TRIPS waiver for COVID-19 vaccines, promoting vaccine equity and strengthening the bonds between nations.

Thoughts on India’s Health Diplomacy

- In recent years, India has established itself as the world’s ‘pharmacy hub’, and this claim was proven once again when it delivered COVID-19 vaccines to its citizens, neighbouring nations and across the globe.

- Following the philosophy of humanitarianism through the principle of ‘Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam’, India has decided to provide the COVID-19 health assistance to its immediate neighbouring countries.

- India always has prepared to help out the countries in emergencies such as tsunamis, floods, earthquakes, even pandemics/endemics and so on. When neighboring countries faced the daunting task of providing timely treatment, medicines and vaccines, India took a humanitarian view of the global health crisis; and decided to provide vaccines to the neighbouring countries. Providing vaccines is considered an essential element of India’s Neighbourhood First Policy.

Overview of India’s Pharma Sector

- The pharmaceutical industry in India was valued at an estimated US$42 billion in 2021.

- India is the world's third largest provider of generic medicines by volume, with a 20% share of total global pharmaceutical exports.

- It is also the largest vaccine supplier in the world by volume, accounting for more than 50% of all vaccines manufactured in the world.

- Major pharmaceutical hubs in India are: Vadodara, Ahmedabad, Ankleshwar, Vapi, Baddi, Sikkim, Kolkata, Visakhapatnam, Hyderabad, Bangalore, Chennai, Navi Mumbai, Mumbai, Pune and Aurangabad.

Some Challenges for the Indian Pharmaceutical Industry

Highly fragmented industry

- The Indian pharma industry is highly fragmented. The market is overloaded with generic manufacturers.

- This is a cause for concern because high fragmentation causes instability, volatility and uncertainty.

‘Out of Pocket (OoP) expenditure

It is limiting the access to medicines wherein, that Indian Insurance section does cater to patients in IP, and not in OP (Out Patient scenario), that causes quite a dent.

Talent Pool

- In India, the demand for these services has outstripped supply. There is a huge shortfall in ‘Healthcare Manpower’ of the country, right from Pharmacists, Nurses and Doctors and related.

A lack of a stable pricing and policy environment

- The challenge created by unexpected and frequent domestic pricing policy changes in India.

- It has created a vague environment for investments and innovations.

Lack in innovation

- India is rich in its manpower and talent. The government needs to invest in research initiatives and talent to grow India’s innovation.

Dependency for raw material

- India is heavily dependent on other countries for active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) and other intermediates. 80% of the APIs are imported from China.

- So India is, therefore, at the mercy of supply disruptions and unpredictable price fluctuations.

- Implementation of infrastructure improvement in the field of internal facilities is necessary to stabilize supply.

Some recent Reforms

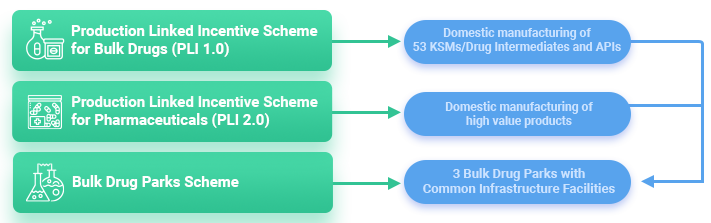

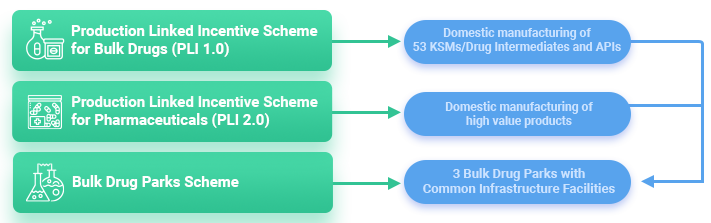

- To foster an Atmanirbhar Bharat by enhancing the R&D, high-value production capabilities, import substitution and domestic manufacture of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API)the government has introduced a US$2 billion incentive program which will run from 2021-22 to 2027-28.

- In 2019 the Department of Pharmaceuticals announced that as part of the Make in India initiative, drugs for local use and exports must have 75% and 10% local APIs respectively and a bill of material must be produced for verification.

- The Production Linked Incentive (PLI) Scheme for promotion of domestic manufacturing of critical Key Starting Materials (KSMs)/Drug Intermediates (DIs) and Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) in India.

Way Ahead

- India needs user friendly government policy for the common man to establish small scale, raw material manufacturing units/ incubators in all states. This will improve availability of raw materials to manufacture generic drugs at affordable rates.

- The government and industry should facilitate the pharmacist community to become entrepreneurs and promote incubators’ establishment.

- Raw material produced from small scale units should be properly validated in the testing laboratoryof the state to ascertain their quality specifications.

- There is a need for a functional testing laboratory in every stateto fasten the work of specification of raw materials.

- Small scale produces may be re-processed in another industry or via a chain of industry for quality productsthat can be used for parenteral/tailor-made formulations.

- Skilled manpower from academic institutionscan be achieved through continuing education programmes.

- Research schemes should be initiated by the industry via direct contact with identified researcher/faculty.

- Incentives should be paid to students contributing towards development of any research formula for the industry.

- Develop strategies for raw material producing units with user friendly government policy for the small scale industry.

- There is a need for qualified workforce and optimization of workforce.

- It is important to promote approvals of pharmaceutical infrastructure and development, get clearance from the environment ministry and offer subsidies and tax exemptionsto offer the much-needed boost to the Indian pharma industry.

- Focus on API manufacturing so that they can less rely on imported APIs. This can be fulfilled in several ways, including constructing dedicated zones for the manufacture of APIs.

- Regulatory authorities have to simplify the approval process because investment in emerging research and development (R & D) fields is much higher than generic ones. Working with other global regulatory bodies could help encourage pharmaceutical growth in India.

- AI can be usedin almost every pharmaceutical industry for drug discovery, development, manufacturing, and marketing. AI can make all business operations efficient, cost-effective, and hassle-free.

https://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-worlds-pharmacy-unga-president-8119737/