Description

Disclaimer: Copyright infringement not intended.

In News

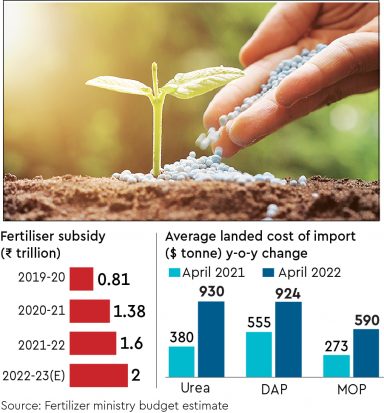

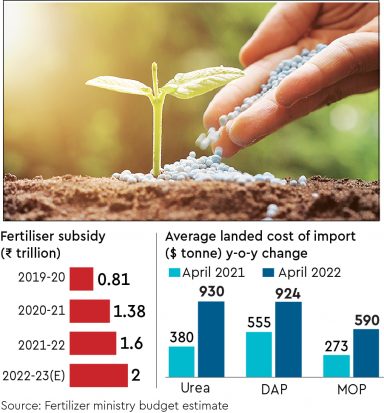

- India’s fertilizer subsidy expenses could touch Rs 2 trillion in 2022-23 because of a sharp spike in global prices of urea, di-ammonium phosphate (DAP) and muriate of potash (MoP) in the last one year: Fertilizer Ministry.

- The fertilizer subsidy was at Rs 1.6 trillion in 2021-22.

- India meets about 75-80% of the volume of consumption of urea from domestic production while the rest is imported from Oman, Egypt, the UAE, South African and Ukraine.

- Nearly half of its DAP requirement are imported via (mainly from West Asia and Jordan) while the domestic MoP demand is met solely through imports (from Belarus, Canada and Jordan, etc).

What is fertilizer subsidy?

- Farmers buy fertilizers at MRPs (maximum retail price) below their normal supply-and-demand-based market rates or what it costs to produce/import them.

- The MRP of neem-coated urea, for instance, is fixed by the government at Rs 5,922.22 per tonne, whereas its average cost-plus price payable to domestic manufacturers and importers comes to around Rs 17,000 and Rs 23,000 per tonne, respectively.

- The difference, which varies according to plant-wise production cost and import price, is footed by the Centre as subsidy.

- The MRPs of non-urea fertilisers are decontrolled or fixed by the companies.

- The Centre, however, pays a flat per-tonne subsidy on these nutrients to ensure they are priced at “reasonable levels.

- Decontrolled fertilisers, thus, retail way above urea, while they also attract lower subsidy.

|

The only regulated Fertilizer

Urea is the only fertilizer at present with pricing and distribution being controlled statutorily by the Government.

The Central Govt. pays subsidy on urea to fertiliser manufacturers on the basis of cost of production at each plant and the units are required to sell the fertilizer at the government-set Maximum Retail Price (MRP).

Thus, no one can sell urea above the MRP declared by the Govt. Under the Concession Scheme, the MRP for each fertilizer is indicative in nature.

|

How is the subsidy paid and who gets it?

- The subsidy goes to fertiliser companies, although its ultimate beneficiary is the farmer who pays MRPs less than the market-determined rates.

- From March 2018, direct benefit transfer (DBT) system was introduced, wherein subsidy payment to the companies would happen only after actual sales to farmers by retailers.

- Each retailer has a point-of-sale (PoS) machine linked to the Department of Fertilisers’ e-Urvarak DBT portal.

- Anybody buying subsidised fertilisers is required to furnish his/her Aadhaar unique identity or Kisan Credit Card number.

- Only upon the sale getting registered on the e-Urvarak platform can a company claim subsidy, with these being processed on a weekly basis and payments remitted electronically to its bank account.

The Challenges of Subsidizing Fertilizer Use in India

- India is the second-largest user of fertilizer in the world, after China. Subsidies on fertilizers were introduced more than 40 years ago to make them affordable to farmers – and ultimately, to ensure food security for the country.

- The subsidy bill has grown exponentially over the years. From just $700 million in 1990-91, it went to nearly $11 billion in 2017-18. Fertilizer is the country’s second-largest subsidy payment, after food.

- But this increase in expenditure hasn’t necessarily benefited farmers. An estimated 65% of the fertilizer produced does not reach the intended beneficiaries – that is, small and marginal farmers, according to government data.

- A bulk of the subsidy is given in the form of urea, which makes up 70% of all fertilizer used in India.

- The government sets an artificially low price for each quintal (equal to 100 kilograms) of urea, which buyers (i.e.: farmers) pay to the retailer (i.e.: fertilizer shops).

- These retailers are the last-mile touch-points that sell fertilizer to farmers on a commission basis. A retailer is given a license by the state government on the basis of a pre-defined selection criteria. The gap between this sale price and the cost of producing the urea is paid by the government to the manufacturer.

- There are no restrictions on who can buy the subsidized fertilizer, or on how much they can buy. This has led to the

- overuse of fertilizers in cultivation, and

- diversion of urea to other industries (like dairy, textile, paint, fisheries, etc.) and to neighboring countries like Bangladesh and Nepal (through organized black market players who buy it in the guise of farmers and sell it for a profit).

Steps taken

- Mindful of these leakages, the Indian government has been taking steps to reform the system, using technology.

- It implemented the Mobile Fertilizer Management System to digitize the fertilizer distribution supply chain.

- In 2016 it took its most significant step, when it piloted a Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) system to pay the subsidy. The pilot was followed by a pan-India rollout in March of 2018.

- In the new DBT system, manufacturers get paid only after the retailer has sold the fertilizer to “authenticated” individuals. That means the buyer is required to prove his identity at the time of purchasing the fertilizer. Preferably with Aadhaar.

- The buyer also has to give his fingerprints on a Point of Sale machine possessed by the retailer.

- Once the Point of Sale machine verifies the buyer’s identity, the retailer sells them the fertilizer at the subsidized price, the sale is recorded in the fertilizer management system, and the proportionate subsidy is remitted to the manufacturer.

- The biggest benefit of the DBT system is that, for the first time, it allows the government to know exactly who is buying the fertilizer.

- However, it’s important to note that the system doesn’t verify if the buyer is a farmer, since there is no database of farmers in India.

- Still, despite these issues, the DBT system has made an impact – especially in increasing transparency.

Further reforms

- There is scope for more efficiency, and the government is already talking about switching to another system — one where it would credit the subsidy directly into the bank account of farmers.

- The government already provides such direct transfers for cooking fuel subsidies and pension payments.

- In these cases, a pre-defined amount of money is deposited directly into the beneficiary’s bank account.

- However, replicating this model for fertilizer subsidies is more complex, partly because the government doesn’t have a list of beneficiaries (i.e.: a database of farmers).

Solutions for Connecting Subsidies Directly with Farmers

- For an optimal fertilizer subsidy transfer, the first order of business would be to create a list of beneficiary farmers, including tenant farmers (who farm land owned by others, paying rent with cash or with a portion of the produce). Existing databases like the PM Kisan list (which includes the registered farmers under the Indian government’s PM Kisan cash transfer scheme) can be a starting point.

- The next step would be to determine how much subsidy each beneficiary is entitled to, depending on the farmers’ land holdings, geo-climatic conditions, crop types, soil health status, etc.

- Crediting farmers’ bank account could be a solution. Farmers could then buy fertilizer at market price from the retailers.

Farmer’s concerns

- 65% of farmers in India don’t want to receive the subsidy via bank transfer.

- This is likely because they have faced many problems with similar programs in recent years, for instance, when they were supposed to receive bank transfers in lieu of a liquefied petroleum gas subsidy.

- They either never received the payment or it was delayed, and farmers fear the same would happen with the fertilizer subsidy.

- Another concern is that if the subsidy amount is not available on time, it would increase their financial burden. They would have to buy the fertilizer at high, non-subsidized prices, and potentially be forced to borrow money to do so.

- Farmers today pay Rs 295 – 325 ($4 – $4.50) for a bag of urea, whereas its non-subsidized price would be between Rs 950 -1,100 ($13 to $15). To shell out Rs 1,100 per bag upfront would be too burdensome for many of India’s small farmers.

- Then there is the hassle of banking. Farmers would have to make multiple trips to banking points to withdraw cash, and then another trip to the fertilizer retailer. These trips translate to lost opportunity costs for farmers.

Way Ahead

- Until the government can fix all the hiccups in the bank transfer model, there can be an alternative model for the subsidy transfer: creating a virtual account for farmers.

- This wouldn’t be a bank account, but rather a digital record of how much fertilizer subsidy a farmer is entitled to, how much he has used, and what is remaining.

Virtual Account

- A virtual account could be opened for all eligible beneficiaries on a government platform. At the beginning of India’s two major crop seasons, namely the kharif and rabi seasons, the government would credit the subsidy to the farmer’s virtual account. The farmer would get an SMS or a call on his registered mobile number, showing how much he is entitled to.

- To buy the fertilizer, the farmer would authenticate himself with his Aadhaar card and the Point of Sale machine available at the retailer, then pay the subsidized amount. The gap between what he pays and the cost of manufacture would be deducted from the farmer’s virtual account. It would be transferred to the fertilizer manufacturer within a stated period of time.

- This system would have two advantages. It wouldn’t create additional hassles for the farmer.

- He’d continue buying the fertilizer at the subsidized rate, without having to worry about whether the subsidy has reached his bank account or not.

- At the same time, the government would have better information about who is using the subsidy and by how much. In a way, it would further refine the Direct Benefit Transfer system that is in place now.

- Once the banking and payment infrastructure is strengthened, the government can create a pilot for direct bank transfers.

- Once farmers have had the opportunity to experience both models, the government will be able to determine the most suitable model for all stakeholders.

Read: https://www.iasgyan.in/daily-current-affairs/nano-urea-and-urea-sector

https://www.financialexpress.com/economy/fertiliser-subsidy-spend-to-touch-rs-2-trillion-in-fy23/2497057/