Fiscal relations in India define how financial powers, taxation rights, and expenditure responsibilities are shared between the Centre and the States. The introduction of GST has centralised major taxation powers, reducing States’ fiscal autonomy and increasing their dependence on Central transfers, which account for about 44% of their total revenues. Rising cesses and surcharges outside the divisible pool further limit States’ resources. To strengthen cooperative fiscal federalism, India needs reforms such as expanding States’ tax share, including cesses in the divisible pool, rationalising centrally sponsored schemes, and empowering local governments for better fiscal balance and accountability.

Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: The Hindu

India’s fiscal system has undergone major reforms since the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in 2017. While GST simplified indirect taxation, it has also significantly changed the resource position and fiscal autonomy of the States. With the end of GST compensation, many States now face rising expenditure needs but limited revenue flexibility.

Fiscal relations refer to the financial arrangements between different levels of government — mainly the Union (Central) Government and the State Governments — in a federal system like India.

They define how powers to raise revenue and responsibilities to spend that revenue are divided between the Centre and the States.

Constitutional Basis: The Indian Constitution lays down fiscal relations mainly in Articles 268 to 293 (Part XII), covering:

Role of the Finance Commission: The Finance Commission, established under Article 280, is a constitutional body that reviews fiscal relations every five years. It recommends:

|

Period / Phase |

Key Developments |

Impact on Fiscal Relations |

Data / Examples |

|

Pre-Independence (Before 1947) |

• Centralised financial control under British Government. • Provinces had very limited taxation powers. |

• Highly unitary system — weak fiscal autonomy for provinces. |

• Provinces depended on grants from the Centre; no revenue-sharing mechanism. |

|

1919 – Government of India Act |

• Introduced Diarchy (division between “Reserved” and “Transferred” subjects).• Some provincial powers in taxation (land revenue, excise). |

• First step toward decentralisation of finances. |

• Provinces collected small taxes but remained dependent on central grants. |

|

1935 – Government of India Act |

• Created a federal financial structure. • Divided subjects and tax powers among Federal, Provincial, and Concurrent Lists. |

• Foundation for India’s post-independence fiscal system. |

• Provinces gained powers over sales tax and land revenue. |

|

Post-Independence (1950 Constitution) |

• Constitution (Articles 268–293) defined fiscal relations. • Established Finance Commission (Art. 280) for periodic devolution. |

• Created a structured system of revenue sharing between Centre and States. |

• 1st Finance Commission (1951) recommended grants-in-aid and tax-sharing formulas. |

|

1950s–1970s |

• Early Finance Commissions focused on stabilising State finances.• Rise of Five-Year Plans and Plan Transfers. |

• Strengthened vertical fiscal balance; but increased Centre’s role via Planning Commission. |

• 5th Finance Commission (1969) introduced gap-filling approach for needy States. |

|

1980s–1990s (Reform Era) |

• Economic liberalisation (1991).• Growing Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS). |

• Increased centralisation — Centre controlled large fiscal transfers through schemes. |

• CSS accounted for ~60% of plan expenditure in early 1990s. |

|

2000 (80th Amendment) |

• Shifted from tax-specific sharing to global sharing of all central taxes. |

• Made tax devolution more flexible and predictable. |

• Recommended by 10th Finance Commission (1995). |

|

2014 – NITI Aayog Formation |

• Replaced Planning Commission.• Reduced discretionary plan grants. |

• Enhanced importance of Finance Commission transfers. |

• Direct impact on States’ fiscal autonomy. |

|

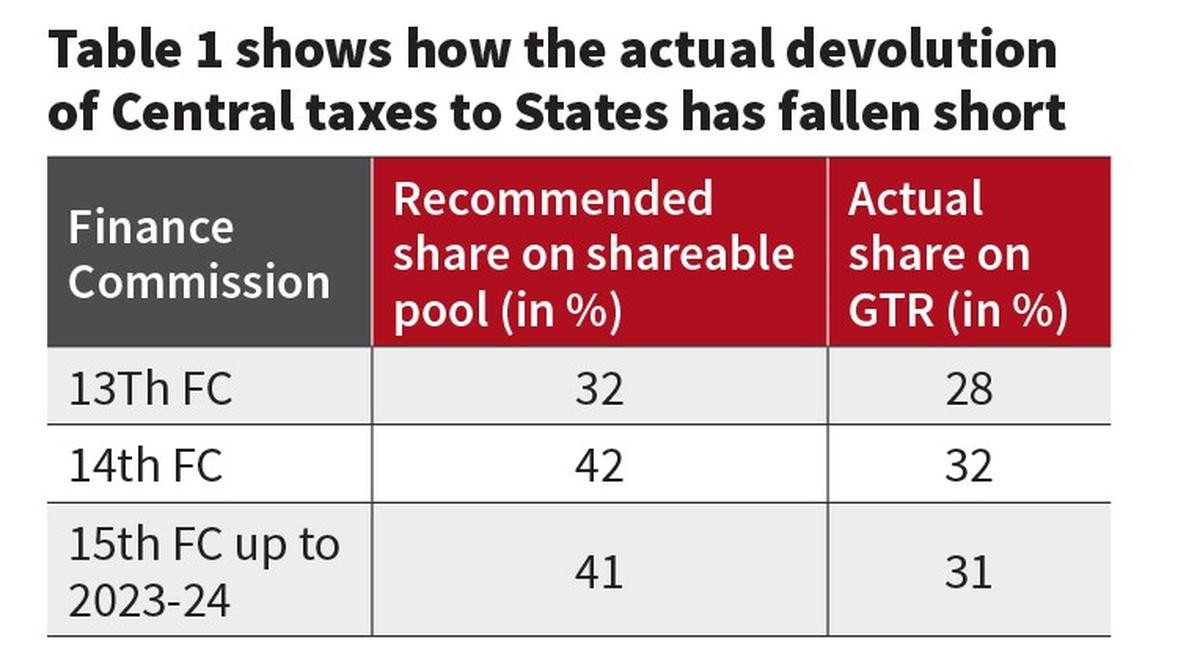

2015 – 14th Finance Commission |

• Increased States’ share of central taxes from 32% → 42%. |

• Major step toward fiscal federalism; more untied funds to States. |

• States’ combined share of central taxes rose by ₹3.8 lakh crore (FY2015–20). |

|

2017 – GST Implementation (101st Amendment) |

• Introduced unified indirect tax regime under GST Council.• Subsumed many State taxes (VAT, Octroi, Entry tax). |

• Reduced States’ independent revenue powers but promoted cooperative decision-making. |

• GST collections crossed ₹1.8 lakh crore/month average in 2025 (Ministry of Finance). |

|

2020–2025 (Post-GST Era) |

• End of GST compensation (June 2023).• Rising use of cesses and surcharges by Centre (outside divisible pool). |

• Fiscal strain on States; demand for restructuring revenue-sharing formula. |

• Cesses & surcharges: ₹4.23 lakh crore in 2025–26 BE (Union Budget 2025). |

|

Current Trends (2025) |

• States demand greater fiscal autonomy, predictable transfers, and inclusion of cesses in divisible pool. |

• Need for rebalancing fiscal power and strengthening cooperative federalism. |

• States’ dependence on Central transfers: ~44% on average (RBI, 2024). |

Source: The Hindu

|

Practice Question Q. Discuss the major challenges in Centre-State fiscal relations in India and suggest measures to strengthen cooperative fiscal federalism. (150 words) |

Fiscal relations refer to the financial relationship between the Centre and the States, including the division of taxation powers, sharing of revenues, and allocation of grants and loans to ensure balanced development and efficient governance.

The Finance Commission (Article 280) recommends how taxes collected by the Centre are distributed between the Union and the States, and also suggests principles for grants-in-aid to States to reduce fiscal imbalances.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved