Disclaimer: Copyright infringement not intended.

Context

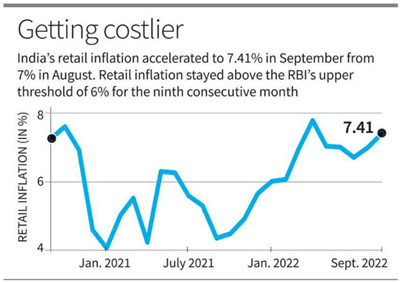

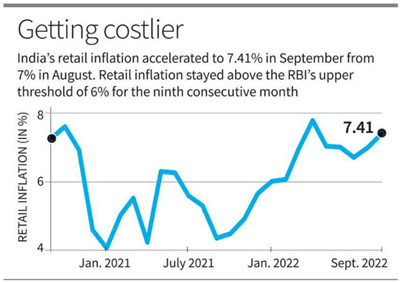

- India’s retail inflation accelerated to 7.41% in September from 7% in August. Food price inflation surging sharply from 7.62% in August to 8.6% in September - the National Statistical Office (NSO).

What is Inflation?

- Inflation refers to a sustained increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy over a period of time.

- It is the rise in the prices of most goods and services of daily or common use, such as food, clothing, housing, recreation, transport, consumer staples, etc.

- Inflation measures the average price change in a basket of commodities and services over time.

- The opposite and rare fall in the price index of this basket of items is called ‘deflation’.

- Inflation is indicative of the decrease in the purchasing power of a unit of a country’s currency. This is measured in percentage.

Measures of Inflation in India:

- In India, the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation measures inflation.

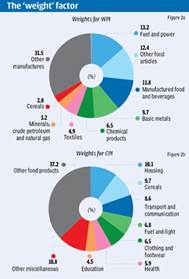

- There are two main set of inflation indices for measuring price level changes in India – the Wholesale Price Index (WPI) and the Consumer Price Index (CPI).GDP deflator is also used to measure inflation.

Consumer Price Index

- Consumer Price Index or CPI is an index measuring retail inflation in the economy by collecting the change in prices of most common goods and services used by consumers.

- CPI is calculated for a fixed list of items including food, housing, apparel, transportation, electronics, medical care, education, etc. The price data is collected periodically, and thus, the CPI is used to calculate the inflation levels in an economy.

- In India, there are four consumer price index numbers, which are calculated, and these are as follows:

- CPI for Industrial Workers (IW)

- CPI for Agricultural Labourers (AL)

- CPI for Rural Labourers (RL) and

- CPI for Urban Non-Manual Employees (UNME).

- While the Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation collects CPI (UNME) data and compiles it, the remaining three are collected by the Labour Bureau in the Ministry of Labour.

WPI

- Wholesale Price Index, or WPI, measures the changes in the prices of goods sold and traded in bulk by wholesale businesses to other businesses.

- The numbers are released by the Economic Advisor in the Ministry of Commerce and Industry.

- An upward surge in the WPI indicates inflationary pressure in the economy and vice versa.

- The quantum of rise in the WPI month-after-month is used to measure the level of wholesale inflation in the economy. Base year: 2011-12. (In the calculation of an index the base year is the year with which the values from other years are compared).

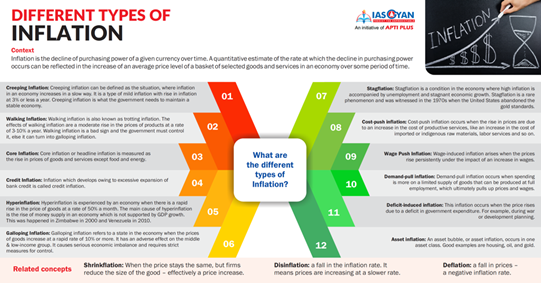

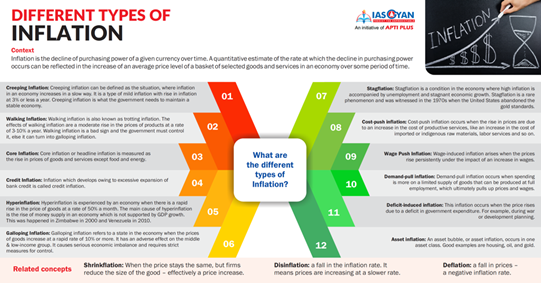

Types of Inflation:

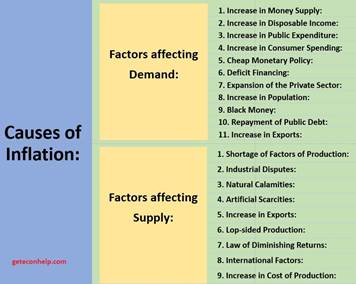

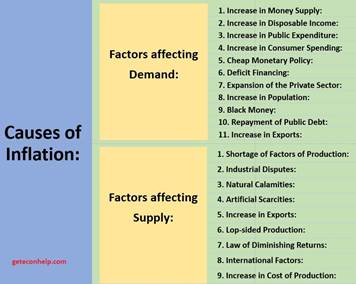

What are the causes of inflation?

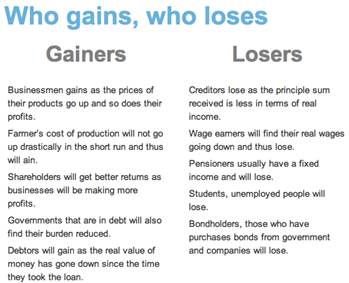

What are the effects of inflation?

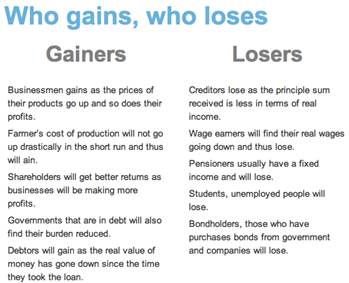

- In the short term, inflation creates winners and losers, but in the eventual analysis, everyone suffers if it stays persistently high.

- It reduces people’s purchasing power. Even in normal times, this would have restricted people’s ability to purchase things, but coupled with reduced incomes and job losses, households would struggle even more. The poor are the worst affected because they have little buffer to sustain through long periods of high inflation.

- It reduces overall demand. The eventual fallout of reduced purchasing power is that consumers demand fewer goods and services. Typically, non-essential demands such as a vacation get curtailed while households focus on the essentials.

- It harms savers and helps borrowers. High inflation eats away the real interest earned from keeping one’s money in the bank or similar savings instruments. Earning a 6% nominal interest from a savings deposit effectively means earning no interest if inflation is at 6%. By the reverse logic, borrowers are better off when inflation rises because they end up paying a lower “real” interest rate.

- It helps the government meet debt obligations. In the short term, the government, which is the single largest borrower in the economy, benefits from high inflation. Inflation also allows the government to meet its fiscal deficit targets.

- Mixed results for corporate profitability. In the short term, corporates, especially the large and dominant ones, could enjoy higher profitability because they might be in a position to pass on the prices to consumers. But for many companies, especially smaller ones, persistently higher inflation will reduce sales and profitability because of lower demand.

- It worsens the exchange rate. High inflation means the rupee is losing its power and, if the RBI doesn’t raise interest rates fast enough, investors will increasingly stay away because of reduced returns.

- It leads to expectations of higher inflation. Persistently high inflation changes the psychology of people. People expect future prices to be higher and demand higher wages. But this, in turn, creates its own spiral of inflation as companies try to price goods and services even higher.

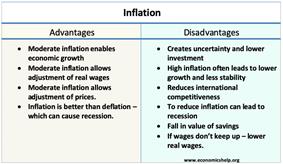

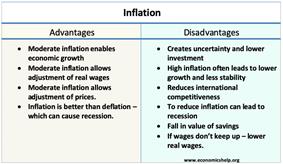

What is the trade-off between growth and inflation?

- In any economy, there are two overwhelming concerns for policymakers: promoting fast economic growth, and maintaining price stability. Both are important. If fast economic growth comes with a high level of inflation then it undermines future growth in two broad ways.

- One, high inflation changes consumer behaviour: if prices are rising fast, it makes sense to buy things today rather than wait for tomorrow.

- But when everyone — or at least a large number of people — starts behaving like this, it only stokes inflation further. Prices rise faster because everyone starts demanding goods today even when they do not need them.

- Two, high inflation also changes producer behaviour. If the price of inputs rise fast, it can eat into the producer’s profitability.

- If the producer passes on the higher prices to consumers — and not every producer is in a position to do that — it can bring down the demand for the product, and they can lose crucial market share that took years, even decades to build.

- Moreover, if prices rise fast, it is difficult to plan future production. That is because the producer remains unsure of the supply and demand situation. A producer could lose heavily by over producing; but they can also lose out by cutting production.

- As such, maintaining price stability is critical to sustaining fast economic growth.

- The key thing to remember is that measures that the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), which is responsible for maintaining price stability, takes to contain inflation, also slow down economic growth. For instance, raising interest rates, which is the most common and fundamental tool to contain inflation, makes it costlier for consumers to borrow and consume and for producers to borrow and produce — thus slowing down overall economic activity.

- By a similar logic, when RBI wants to promote growth, it reduces interest rates, thus giving a boost to credit-driven consumption and production.

What is the actual situation in India right now?

- Under normal circumstances, high inflation happens as a result of high growth — i.e., people producing more, buying more, earning more, etc.

- In such a scenario, even though tamping down on high inflation drags down growth, the situation remains manageable because the economy still continues grow, albeit not as fast.

- But what if the inflation becomes high at a time when economic growth is faltering?

- This is one of the worst scenarios for policymakers. That’s because measures to contain inflation — such as raising interest rates — now risk running the economy aground.

- This is exactly what is happening in India.

- India’s GDP growth rate had been decelerating sharply over the three years leading up to the pandemic. It decelerated from more than 8% in 2016-17 to less than 4% in 2019-20.

- In April 2022, inflation hit the 7.8% mark — the highest it had been since Prime Minister Modi took office in 2014. Since then inflation has stayed around 7% every month.

Why is there a divergence between RBI and the government?

- From May 2022 onward, the RBI started raising the interest rate because by then it was clear that inflation could no longer be ignored, and that, if not contained, it would undermine India’s economic recovery.

- It is noteworthy that the RBI’s main legal mandate is to maintain price stability. It must, by law, keep inflation at 4% with a leeway of two percentage points either side in any particular month.

- But then, these actions by the RBI — and more rate hikes are in store — will drag down economic growth. And that is where the government is concerned.

- With less than two years left for the next general elections in early 2024, the government is struggling to deal with massive and widespread unemployment. While in percentage terms GDP growth rates look rosy, the truth is that in real terms the economy is barely out of the contraction it witnessed during the Covid pandemic.

- So, here’s the essential problem: If RBI continues to tighten monetary policy, it will weaken economic recovery at a time when growth is already faltering and unemployment is already quite high. If RBI ignores inflation then it hits the poor immediately without necessarily guaranteeing that growth and unemployment will be resolved.

But in the situation that the economy today is in, the RBI is struggling to be accountable and, at the same time, having to increasingly depend on the government for fulfilling its mandate.

Reason for this situation:

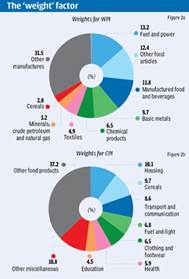

- There’s a simple reason for the RBI’s “failure” to adhere to its inflation-targeting mandate. It has to do with food and beverage items, which have a combined 45.86% weight in the overall CPI.

- Both the “success” of inflation targeting in Modi 1.0 and “failure” in Modi 2.0 has been largely courtesy of food prices.

- That links up to the second issue of monetary policy independence — which basically refers to the central bank being insulated from government interference or electoral pressure in setting its interest rates with a view to achieving low and stable inflation.

- The preponderant weight of food tems in the Indian consumption basket and hence its CPI — in contrast to developed countries where their shares are hardly 10-25% — makes inflation that much less amenable to control through repo interest rate or cash reserve ratio hikes.

- The RBI, then, is forced to rely more on government action to meet inflation targets. Far from acting independently — using monetary policy tools that seek to curb demand by raising borrowing costs for firms and consumers — it has to depend on “supply-side” measures by the government. That translates into monetary dependence, not independence.

- The last two years or less have seen a resurgence of inflation, driven mainly by supply-side factors — from the pandemic and the Ukraine war to extreme weather events.

- The last includes excess rain during September-January 2021-22, the heat wave in March-April and the deficient monsoon in the Gangetic plain states this time.

- These — along with skyrocketing prices of fuel, which have a 6.84% weight in the CPI, over and above the 45.86% of food — have rendered the RBI’s demand-side toolkit to fight inflation ineffective.

Recent government’s supply-side actions that have made the RBI’s job easier:

- In the last one year, the effective import duty on crude and refined palm oil has come down from 30.25% and 41.25% to 5.5% and 13.75%, respectively.

- It’s been even sharper — from 30.25% to nil — for crude soyabean and sunflower oil.

- Modi government banned exports of wheat. This was extended to wheat flour — including atta, maida and rava/ sooji (semolina)

- Exports of broken rice were prohibited. Besides, a 20% duty was imposed on shipments of all other non-parboiled non-basmati rice.

- Sugar exports were moved from the “free” to “restricted” category. Further, total exports for the 2021-22 sugar year (October-September) were capped at 10 million tonnes, which was raised to 11.2 million tonnes on August 1. The export quota for the next sugar year is yet to be announced.

- Centre directed states and union territories to force pulses traders/millers to declare their stocks of tur (pigeon-pea) and upload this information on a weekly basis.

Measures to control Inflation:

Some of the important measures to control inflation are as follows:

Monetary Measures:

(a) Credit Control:

One of the important monetary measures is monetary policy. The central bank of the country adopts a number of methods to control the quantity and quality of credit. For this purpose, it raises the bank rates, sells securities in the open market, raises the reserve ratio, and adopts a number of selective credit control measures, such as raising margin requirements and regulating consumer credit. Monetary policy may not be effective in controlling inflation, if inflation is due to cost-push factors. Monetary policy can only be helpful in controlling inflation due to demand-pull factors.

(b) Demonetisation of Currency:

However, one of the monetary measures is to demonetise currency of higher denominations. Such a measures is usually adopted when there is abundance of black money in the country.

(c) Issue of New Currency:

The most extreme monetary measure is the issue of new currency in place of the old currency. Under this system, one new note is exchanged for a number of notes of the old currency. The value of bank deposits is also fixed accordingly. Such a measure is adopted when there is an excessive issue of notes and there is hyperinflation in the country. It is a very effective measure. But it is inequitable as hurts the small depositors the most.

Fiscal Measures:

The principal fiscal measures are the following:

(a) Reduction in Unnecessary Expenditure:

The government should reduce unnecessary expenditure on non-development activities in order to curb inflation. This will also put a check on private expenditure which is dependent upon government demand for goods and services. But it is not easy to cut government expenditure. Though this measure is always welcome but it becomes difficult to distinguish between essential and non-essential expenditure. Therefore, this measure should be supplemented by taxation.

(b) Increase in Taxes:

To cut personal consumption expenditure, the rates of personal, corporate and commodity taxes should be raised and even new taxes should be levied, but the rates of taxes should not be so high as to discourage saving, investment and production. Rather, the tax system should provide larger incentives to those who save, invest and produce more.

Further, to bring more revenue into the tax-net, the government should penalise the tax evaders by imposing heavy fines. Such measures are bound to be effective in controlling inflation. To increase the supply of goods within the country, the government should reduce import duties and increase export duties.

(c) Increase in Savings:

Another measure is to increase savings on the part of the people. This will tend to reduce disposable income with the people, and hence personal consumption expenditure. But due to the rising cost of living, people are not in a position to save much voluntarily.

Keynes, therefore, advocated compulsory savings or what he called ‘deferred payment’ where the saver gets his money back after some years. For this purpose, the government should float public loans carrying high rates of interest, start saving schemes with prize money, or lottery for long periods, etc. It should also introduce compulsory provident fund, provident fund-cum-pension schemes, etc. All such measures increase savings and are likely to be effective in controlling inflation.

(d) Surplus Budgets:

An important measure is to adopt anti-inflationary budgetary policy. For this purpose, the government should give up deficit financing and instead have surplus budgets. It means collecting more in revenues and spending less.

(e) Public Debt:

At the same time, it should stop repayment of public debt and postpone it to some future date till inflationary pressures are controlled within the economy. Instead, the government should borrow more to reduce money supply with the public.

Like monetary measures, fiscal measures alone cannot help in controlling inflation. They should be supplemented by monetary, non-monetary and non-fiscal measures.

Other Measures:

The other types of measures are those which aim at increasing aggregate supply and reducing aggregate demand directly.

(a) To Increase Production:

The following measures should be adopted to increase production:

(i) One of the foremost measures to control inflation is to increase the production of essential consumer goods like food, clothing, kerosene oil, sugar, vegetable oils, etc.

(ii) If there is need, raw materials for such products may be imported on preferential basis to increase the production of essential commodities,

(iii) Efforts should also be made to increase productivity. For this purpose, industrial peace should be maintained through agreements with trade unions, binding them not to resort to strikes for some time,

(iv) The policy of rationalisation of industries should be adopted as a long-term measure. Rationalisation increases productivity and production of industries through the use of brain, brawn and bullion.

(v) All possible help in the form of latest technology, raw materials, financial help, subsidies, etc. should be provided to different consumer goods sectors to increase production.

(b) Rational Wage Policy:

Another important measure is to adopt a rational wage and income policy. Under hyperinflation, there is a wage-price spiral. To control this, the government should freeze wages, incomes, profits, dividends, bonus, etc.

But such a drastic measure can only be adopted for a short period as it is likely to antagonise both workers and industrialists. Therefore, the best course is to link increase in wages to increase in productivity. This will have a dual effect. It will control wages and at the same time increase productivity, and hence raise production of goods in the economy.

(c) Price Control:

Price control and rationing is another measure of direct control to check inflation. Price control means fixing an upper limit for the prices of essential consumer goods. They are the maximum prices fixed by law and anybody charging more than these prices is punished by law. But it is difficult to administer price control.

(d) Rationing:

Rationing aims at distributing consumption of scarce goods so as to make them available to a large number of consumers. It is applied to essential consumer goods such as wheat, rice, sugar, kerosene oil, etc. It is meant to stabilise the prices of necessaries and assure distributive justice. But it is very inconvenient for consumers because it leads to queues, artificial shortages, corruption and black marketing. Keynes did not favor rationing for it “involves a great deal of waste, both of resources and of employment.”

Final Say:

- We flag two aspects of the recent inflation in India.

- The first is the differential inflation across commodity groups. For the month of April, annual inflation in India was over 7 per cent but food inflation, or the rise in the price of food, was higher at over 8 per cent. It is a general feature of inflation in India that it tends to be led by the growth of food prices, which has a cascading effect on prices elsewhere in the economy.

- The second aspect of the current inflation is that it commenced some time ago. Annual inflation on a monthly basis began to rise from September 2020, and rose every month thereafter up to April 2021. While the rising price of crude oil is surely a factor, in April 2022, the direct contribution of “food” to overall inflation was close to 48 per cent; the contribution of “fuel and light” was less than 10 per cent. So, we have reason to believe that there is a domestic factor at work in the current inflation.

- Public policy’s focus, whether it had to do with the now-repealed farm reform laws or fixation of minimum support prices (MSP), was to make agriculture market-led, resource-efficient and environmentally-sustainable.

- Those structural transformation goals have been set back by the war in Ukraine and the effects of climate change.

- The latter is seen clearly from the excess rains during September-January 2021-22, followed by sudden temperature spikes in March-April, a severe monsoon deficit across the Gangetic plain states, and the wet spell after mid-September just when the current kharif crop had entered the harvesting stage.

- In the case of wheat, a single harvest failure has resulted in public stocks plunging close to the normative minimum buffer.

- What should the government do?

- The options are limited when farmers are yet to commence wheat sowing and the next crop will not arrive in the mandis before late-March.

- Nor are imports commercially viable; the landed cost of even the cheapest wheat from Russia will be above Rs 30 per kg.

- The only import that is possible today is on government account. It may be worth contracting 2-3 mt of such imports for replenishing public stocks and undertaking open market operations to keep a lid on prices.

- It goes without saying that to control an economic phenomenon, we need to understand what underlies it. This holds equally for inflation.

- We have already indicated what drives inflation in India. Rising agricultural prices, of foodstuffs in particular, are the driving force. Now, inflation control in India will have to approach the problem suitably.

- Monetary policy working via changes in the interest rate is a blunt instrument for the kind of inflation we invariably experience in India. There is persistent food price inflation, only varying in degree over time, because there is a continuing imbalance between the supply and demand for food, with the latter inevitably the greater, except in the case of cereals.

- In such a scenario, suppose monetary policy were to cure inflation via demand contraction: Unless an improvement were to be brought about on the supply side, whereby food supply can henceforth be increased at a constant price, inflation is bound to revive when growth revives, and demand expands. We would have returned to square one.

- In India, inflation requires broader economic management that addresses production conditions in agriculture.

https://sansadtv.nic.in/episode/perspective-tackling-inflation-13-october-2022-2