Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: THE HINDU

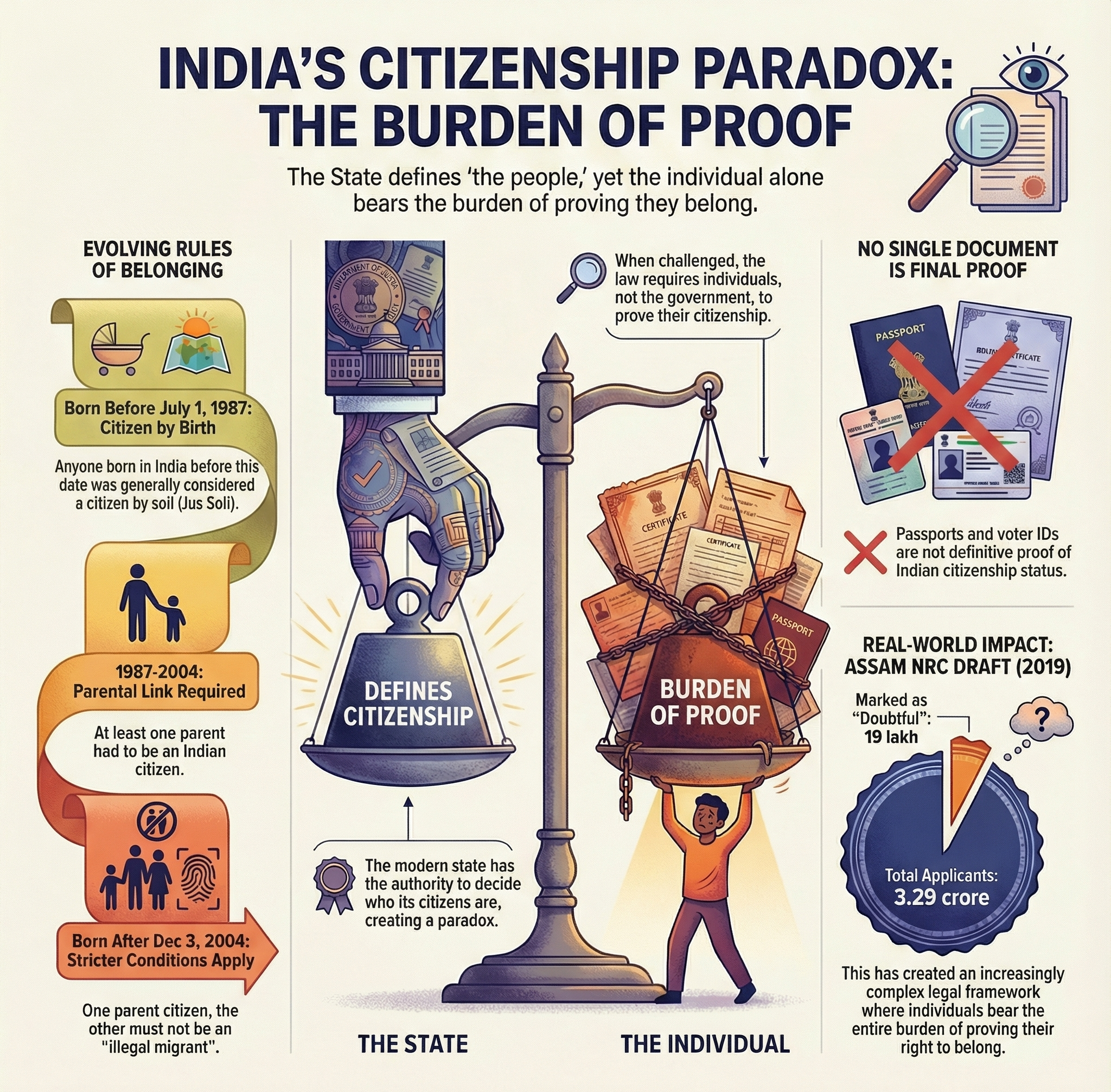

The governance of Indian citizenship presents a fundamental paradox where the sovereign entity, 'the people', ultimately defines the very administrative machinery of the state they create

|

Read all about: INDIAN CITIZENSHIP LAW l IMMIGRATION AND FOREIGNERS ORDER 2025 l DETAINING NON-CITIZENS & THE RULE OF LAW l SUPREME ON AADHAAR & ELECTORAL PROCESSES |

Part II of the Indian Constitution, Articles 5 to 11, deals with citizenship.

A key challenge in Indian citizenship law is the reversal of the burden of proof, requiring the individual, not the state, to prove their citizenship.

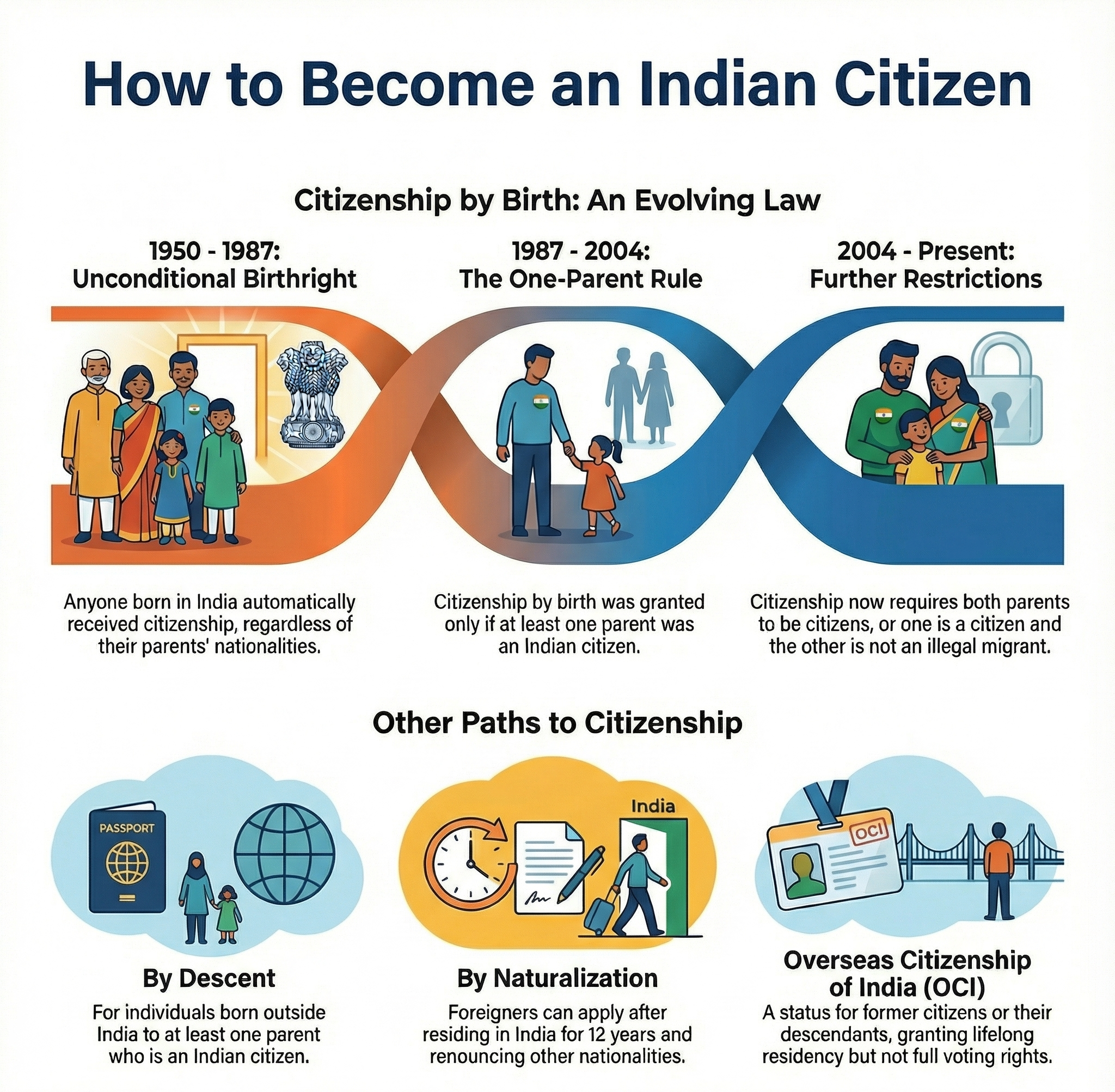

India's approach to citizenship has shifted from the principle of jus soli (right of the soil), which grants citizenship based on birth within a country's territory, towards jus sanguinis (right of blood), which bases citizenship on the nationality of one's parents.

|

Legislation/ Amendment |

Key Provisions |

Principle |

|

The Citizenship Act, 1955 (Original) |

Granted citizenship to anyone born in India between Jan 26, 1950, and July 1, 1987, regardless of parental nationality. |

Pure Jus Soli |

|

1986 Amendment |

For those born between July 1, 1987, and Dec 3, 2004, the individual is a citizen if at least one parent was an Indian citizen at the time of birth. |

Restricted Jus Soli |

|

2003 Amendment |

For those born on or after Dec 3, 2004, the individual is a citizen only if both parents are Indian citizens, or one parent is an Indian citizen and the other is not an illegal migrant. |

Shift towards Jus Sanguinis |

|

Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 (CAA) |

Does not alter birthright citizenship but provides an accelerated path to citizenship for specific religious communities (Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi, Christian) from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan who entered India on or before Dec 31, 2014. |

Introduces religious criteria for naturalization for a specific group. |

National Population Register (NPR): It is a mandatory register of all "usual residents." Data was last collected in 2010 and updated in 2015.

National Register of Citizens (NRC): Intended as the official record of all legal Indian citizens. Currently, the NRC update has only occurred in Assam.

Foreigners' Tribunals (FTs): Quasi-judicial bodies established under the Foreigners Act, 1946, to determine if a person is a foreigner.

Election Commission of India (ECI): The ECI prepares electoral rolls for citizens, but its recent Special Intensive Revision (SIR) exercise is criticised for potentially overstepping into citizenship determination, a power belonging to the Union Home Ministry.

|

Case Study: The Assam NRC The Assam NRC exercise is a case study of the complexities involved in citizenship verification. Background: The NRC update was mandated by the Supreme Court to implement the Assam Accord of 1985, which aimed to address illegal immigration. It used March 24, 1971, as the cut-off date. Section 6A of Citizenship Act: This special provision for Assam, which specifies the 1971 cut-off date, was challenged but upheld as constitutionally valid by a Supreme Court Constitution Bench. Outcome: The final updated NRC list, published in August 2019, excluded over 1.9 million people, raising concerns about potential statelessness and a major humanitarian crisis. Implications: The exercise highlighted the administrative challenges, the difficulty in producing legacy documents for marginalized communities, and the high human cost of such verification processes. |

Challenges

ChallengesBurden of Proof: The requirement for individuals to produce decades-old documents places an unreasonable burden on them.

Risk of Statelessness: Exclusion from registers like the NRC without clear legal recourse or bilateral agreements with neighboring countries make individuals stateless.

Administrative Discretion: The process provides vast power in lower-level administrative officials, also the risk of errors and arbitrary decisions.

Politicization of Citizenship: Citizenship has become a highly politicized issue, undermining the secular and inclusive fabric of the nation.

Way Forward

The current framework for citizenship governance faces several challenges that require a balanced and humane approach.

Establish a Fair Legal Framework: Create a uniform, transparent, and simple process for verification that is insulated from political influence.

Strengthen Adjudicatory Bodies: Ensure Foreigners' Tribunals are staffed by judicially trained officials and follow principles of natural justice, offering a fair hearing.

Delink Rights from Documentation: Ensure that basic human rights like access to food, education, and healthcare are not denied to individuals pending the determination of their citizenship status.

Resolving the citizenship paradox demands a just, humane, and transparent process that balances the state's interest in identification with the necessity of upholding individual dignity and preventing the disenfranchisement of genuine residents.

Source: THE HINDU

|

PRACTICE QUESTION Q. Discuss the role of the Supreme Court in upholding fundamental rights against executive and legislative actions pertaining to citizenship in India. 150 words |

The paradox lies in the contradiction where the democratic state, which is theoretically created by 'the people', holds the ultimate power to define who is included in 'the people'. This gives the creation (the state) power over its creator (the people).

Foreigners' Tribunals are quasi-judicial bodies established in India (primarily in Assam) to determine if a person is an "illegal foreigner". Individuals excluded from the NRC or suspected of being foreigners can be referred to these tribunals to prove their citizenship.

The NRC in Assam was a Supreme Court-mandated exercise to create an official register of genuine Indian citizens in the state. Its purpose was to identify and detect undocumented immigrants who may have entered Assam from Bangladesh after March 24, 1971.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved