Copyright infringement not intended

Picture Courtesy: THE HINDU

Context

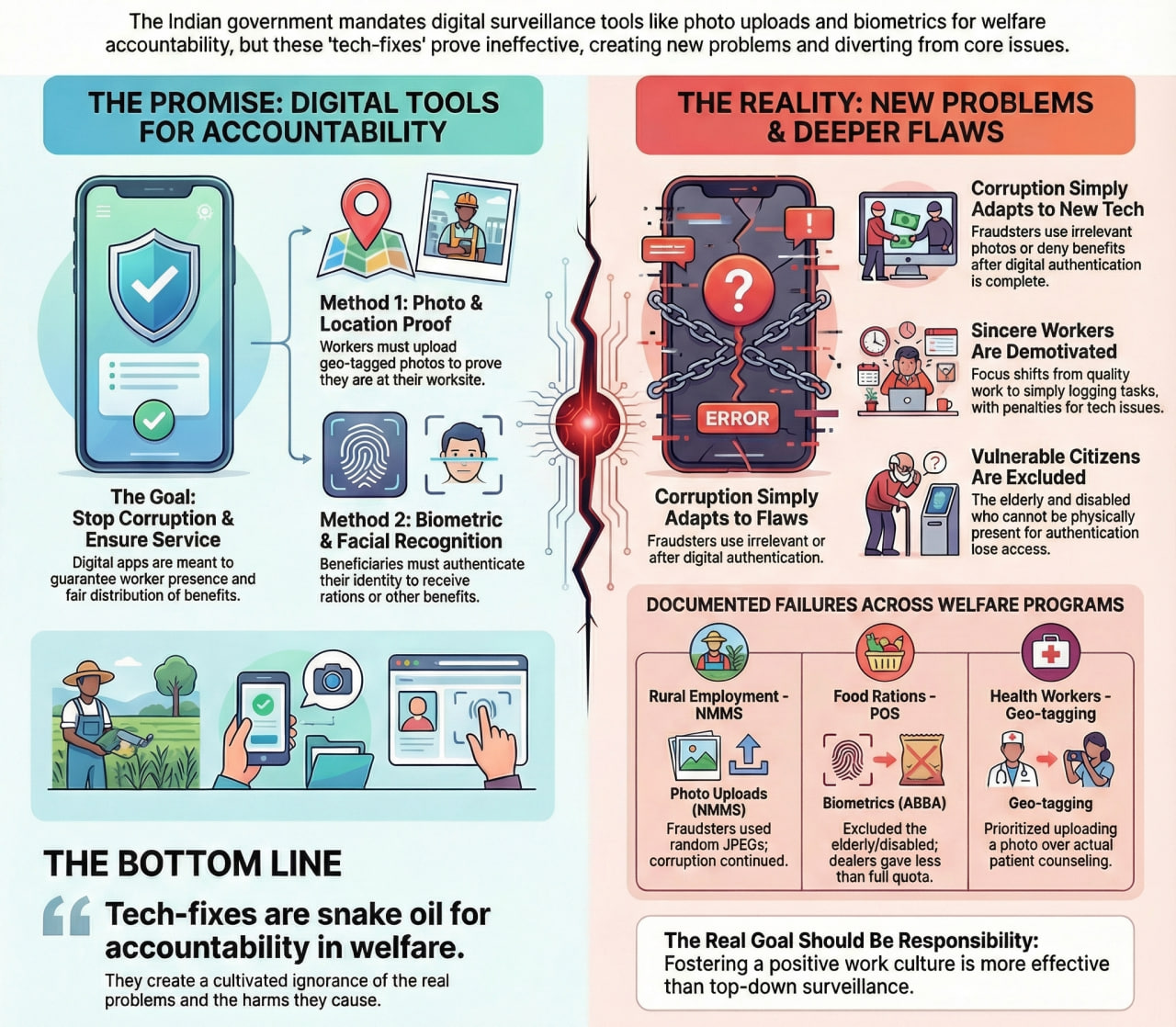

India is increasingly integrating digital surveillance tools like biometric attendance and geo-tagged monitoring into welfare programs to combat corruption and improve efficiency, a strategy often referred to as 'techno-solutionism'.

|

Read all about: Aadhaar: Welfare Access & Exclusion |

What is Digital Surveillance in Welfare Delivery?

The use of mobile applications and digital surveillance tools to monitor frontline government workers and welfare scheme delivery has become widespread in India.

This trend raises critical questions about governance, privacy, and the true meaning of accountability.

Why the Push for Technological Solutions?

Curbing Corruption: To curb leakages and financial fraud, like inflated MGNREGS attendance or PDS food grain diversion.

Enforcing Accountability: Use biometric attendance and geo-tagged, time-stamped applications to curb frontline worker absenteeism and indiscipline.

Centralised Monitoring: Enables real-time, top-down bureaucratic oversight, often bypassing local governance.

Challenges

Technological anti-corruption efforts have had limited success, often causing exclusion and inefficiency.

|

Scheme & Technology |

Objectives |

Outcome & Issues |

|

Ensure transparent, real-time attendance of workers by uploading two geo-tagged photos daily. |

|

|

|

Public Distribution System (PDS): |

Prevent identity fraud and ensure that rations reach only genuine beneficiaries. |

|

|

Poshan Abhiyaan: |

Verify the identity of mothers receiving Take Home Rations (THR) to ensure delivery. |

|

Demotivating the Frontline Workforce

The surveillance system negatively impacts frontline workers, such as Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANMs) and Anganwadi workers, who face unfair penalties despite their efforts, often due to uncontrollable factors like inadequate network coverage.

This system shifts the focus from substantive duties (e.g., counselling a new mother) to procedural tasks (e.g., uploading a photo), destroying morale and eroding the culture of public service.

Consequences of the Surveillance-First Approach

Deepening Social Exclusion

The most vulnerable groups—the elderly, persons with disabilities, and remote rural populations—are the primary victims of technological failures, denying them their legal entitlements.

Violation of Privacy and Dignity

Mandating photographs of beneficiaries without their informed consent violates their dignity and directly challenges the Right to Privacy, which the K.S. Puttaswamy vs Union of India judgement (2017) affirmed as a fundamental right under Article 21.

Confusing Accountability with Responsibility

As highlighted by economists Jean Drèze and Amartya Sen, this approach enforces a mechanical form of accountability (performing pre-specified tasks under threat of penalty) while destroying the spirit of responsibility (an intrinsic motivation to serve the public good).

Way Forward

Way Forward

Strengthen Social Audits

Community-led social audits offer a more effective, democratic, and bottom-up accountability mechanism for welfare schemes than top-down surveillance.

Invest in the Workforce

Improve working conditions for frontline functionaries by providing regular training, filling vacancies, ensuring timely and fair wages, and trusting them as professionals.

Technology for Empowerment, Not Control

Use technology to empower citizens with information, provide effective grievance redressal platforms, and improve supply chain logistics, rather than for policing workers and beneficiaries

Human-Centric Design

Ensure that any technological solution is designed with the most marginalised user in mind, includes offline alternatives, and is backed by a robust, accessible grievance redressal system.

Conclusion

Focusing on surveillance apps is a harmful mistake; they fail to stop corruption, violate rights, create exclusion, and demotivate workers. India must shift from control to trust, empowerment, and democratic accountability for an effective welfare state.

Source: THE HINDU

|

PRACTICE QUESTION Q. "The over-reliance on technology-driven surveillance as a panacea for accountability in welfare schemes often creates more problems than it solves." Critically Analyze. 250 words |

These apps, while intended to improve accountability, often fail to curb corruption and sometimes lead to negative consequences, which include the exclusion of genuine beneficiaries due to technical glitches, and violations of citizens' privacy.

The NMMS application's requirement for geo-tagged attendance photographs has failed to prevent fraud, with the Union Ministry acknowledging the submission of illegitimate photos. This system does not address the core issue of corruption and potentially excludes genuine workers.

ABBA excludes the elderly and disabled who face fingerprint authentication issues or cannot be physically present. This exclusion, coupled with its failure to prevent "quantity fraud" where beneficiaries receive less than their quota, makes it ineffective.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved