|

APPROACH Introduction → Mention time period and significance of Harappan architecture. Body → Discuss salient features (city layout, bricks, drainage, public works, houses, water management, defensive walls, significance). Conclusion → Sum up with why Harappan architecture matters (urban planning, public health, organised civic life). |

The Harappan or Indus Valley people built some of the earliest and most well-planned cities in the world (about 3300–1300 BCE). Their architecture shows careful planning, good engineering and concern for public health.

Salient features of Harappan architecture

Planned cities (grid pattern)

Harappan cities were laid out in a grid of straight streets that met at right angles. The city was usually divided into a raised area called the citadel (for public buildings and big structures) and the lower town (where people lived and worked). This careful planning appears at Mohenjo-daro, Harappa, Dholavira and other sites.

Standardised baked bricks

Most buildings, roads and drains were made from fired (baked) bricks. The bricks were made to a standard ratio so they fit together easily. This uniformity shows a high level of organisation across many towns.

Advanced drainage and sanitation

One of the most impressive features is the covered drainage system. Houses had individual drains and toilets that connected to public drains along the streets. Many drains had inspection holes and soak pits — a clear sign that the Harappans cared about cleanliness and public health.

Wells, reservoirs and water management

Most houses had access to wells. Cities also had large public water structures and systems for storing and using water. Dholavira and Mohenjo-daro had special water tanks and storage arrangements.

Public buildings

The Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro is a large watertight pool used for public or ritual bathing; it was carefully built with two layers of brick and sealed with bitumen to stop leakage. Large granary-like structures (thought to be storehouses) are also found in the citadel areas.

Houses

Typical Harappan houses had one or more rooms arranged around a central courtyard. Courtyards gave light and air and were places for daily work. Some houses had two storeys. Private bathrooms and toilets were common.

Use of materials and technology

Besides baked bricks, Harappans used gypsum, clay, timber and bitumen (natural tar) for waterproofing. They used planned foundations, brick colonnades and sometimes corbelled roofs. These techniques show practical engineering skills.

Specialised areas

Some towns had areas for crafts (bead-making, metal work, pottery) and ports/docks (e.g., Lothal had a dockyard). This separation of activities shows organised urban zoning.

Defensive features and city walls

Many Harappan towns had mud or brick walls and gateways. These may have served to protect against floods and to control trade rather than for war. Excavations show planned gateways and buttressed walls.

Significance

Harappan architecture stands out for its planned towns, standardised bricks, advanced drainage, and public water works such as the Great Bath. These features point to sophisticated urban life, strong organisation, and concern for public welfare in the Indus Valley Civilization.

|

APPROACH Introduction → define Akbar’s syncretism and give timeframe Body → explain Sulh-i-Kul, Ibadat Khana, removal of discriminatory taxes, Din-i-Ilahi, cultural patronage, Rajput alliances, and limitations Conclusion → summarize impact and lasting significance in contemporary times. |

Akbar tried to bring people of different religions together so his large empire could be peaceful and strong. His approach mixed ideas from many faiths — this is called religious syncretism.

Main aspects

Sulh-i-Kul

Akbar adopted the policy called Sulh-i-Kul, meaning universal peace. It said the emperor should treat all religions fairly and not act as the agent of one single faith. In practice this meant officials could rise by merit regardless of religion, and public policies were meant to avoid favouring one community over another. Sulh-i-Kul was both a political and moral idea that helped keep a multi-religious empire together.

Ibadat Khana

At Fatehpur Sikri Akbar created the Ibadat Khana (House of Worship) where scholars, saints and priests of different faiths — Muslims (Sunni and Shia), Hindus, Jains, Christians, Zoroastrians and Sufis — met to discuss religion and philosophy. These debates showed Akbar’s curiosity and encouraged mutual understanding, not forced conversions. The records of these discussions are preserved in sources like the Akbarnama.

Practical reforms

Akbar removed or relaxed practices that singled out non-Muslims. Notable steps included abolishing the pilgrim tax (on Hindus visiting holy places) and the jizya (a poll tax on non-Muslims) during much of his reign. He also allowed the repair and construction of temples, forbade forced conversions of captured people, and stopped restrictions on public Hindu festivals. These moves reduced resentment and brought many local elites into the Mughal fold.

Din-i-Ilahi and personal syncretism

Around 1582 Akbar developed what later writers called Din-i-Ilahi (literally “Divine Faith”). It was not a mass religion but a small, court-level set of ethical rules and rituals that blended elements from Sufism, Hinduism, Christianity and other traditions. Din-i-Ilahi emphasised virtues like generosity, piety and self-control. Critics argued it was eccentric and mainly influenced the emperor’s close circle; it did not become a popular religion.

Patronage of other religious traditions and cultural exchange

Akbar sponsored translations of Sanskrit epics (like the Ramayana and Mahabharata) into Persian, supported Hindu and Jain scholars, and patronised Sufi thinkers and the Jesuit missionaries who visited his court. This cultural exchange made the court a meeting place of ideas and reduced cultural distance between communities.

Political alliances through marriage and appointments

Akbar married Rajput princesses and formed alliances with Hindu rulers, keeping their customs and not forcing conversion. He appointed Hindus to high civil and military posts (e.g., Raja Man Singh), which gave local rulers a stake in the Mughal system and helped political stability. This mix of politics and religion was central to his syncretic success.

Limits and criticisms

Akbar’s policy had limits. Some orthodox Muslim scholars disliked his religious experiments. Din-i-Ilahi remained a court curiosity and faded after his death. Also, some measures were driven by political needs (winning loyalty), not only by theology. Later emperors — especially Aurangzeb — reversed many of Akbar’s policies. So Akbar’s syncretism was powerful but not permanent.

Akbar’s religious syncretism was more than a personal experiment — it was a statesmanlike attempt to ensure peace and stability in a plural society. Though Din-i-Ilahi faded, his broader ideals of Sulh-i-Kul, cultural inclusiveness, and equal respect for all faiths continue to hold meaning in modern India. In a world where communal divisions still threaten harmony, Akbar’s vision reminds us that tolerance, dialogue, and integration are essential for building unity in diversity and for sustaining democratic societies.

|

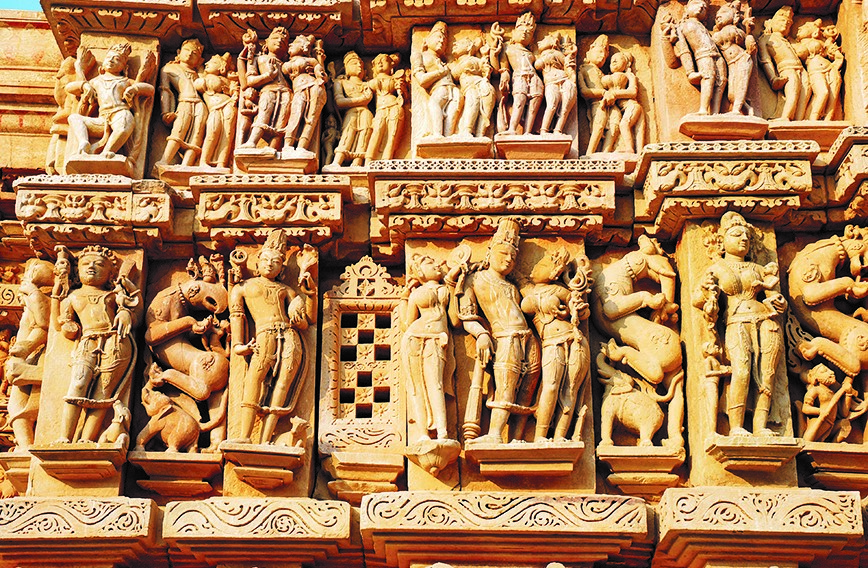

APPROACH Introduction → Mention Chandella dynasty (10th–12th century) and Khajuraho temples, highlighting art filled with energy (vigor) and all aspects of life (breadth of life). Body → Explain vigor (dynamic poses like tribhanga), breadth of life (sacred + secular, dharma–artha–kama–moksha), integration with nature (flora-fauna), and symbolism (shakti–purusha). Conclusion → Sum up that Chandella art made stone “come alive” and remains relevant today for celebrating inclusiveness, harmony, and unity of sacred and worldly life. |

The Chandella dynasty (10th–12th century CE) famous for building the Khajuraho temples in Madhya Pradesh created some of the finest art in India. Their sculptures were not lifeless stones but seemed full of energy (vigor) and all aspects of human existence (breadth of life).

Main Aspects

Vigor and Movement in Sculpture

Breadth of Life – From Sacred to Secular

Integration with Nature and Society

Philosophical and Symbolic Depth

The Chandella sculptors turned stone into a living canvas—filled with vigor, grace, and human emotions. By capturing gods, humans, animals, and nature, they presented the breadth of life in its totality. Even today, the Khajuraho temples remind us that Indian culture values inclusiveness, harmony, and celebration of both the sacred and the worldly.

|

APPROACH Introduction → Begin with a striking fact, set the context by explaining how climate change and sea level rise threaten island nations, and define what is at stake—their existence, culture, and sovereignty. Body → Cover the multiple impacts—physical threats (like flooding and erosion), socio-economic consequences (such as food insecurity and economic losses), and responses/examples from affected countries to show the reality and diversity of challenges. Conclusion → Summarize by emphasizing that sea-level rise is a present crisis, and advocate for urgent global action through both mitigation and adaptation to protect the survival and identity of island nations. |

Climate change, through rising temperatures and melting ice sheets, is causing global sea levels to rise. Over the past 100 years, sea level has already increased by about 20 cm and experts warn that it could rise by up to 1.1 metres by 2100 if greenhouse gas emissions are not controlled. For small island nations like the Maldives, Tuvalu, Kiribati and the Marshall Islands which are only 1–3 metres above sea level this threatens not just land and livelihoods but also their very existence, culture and sovereignty.

Physical and environmental threats

Flooding and land loss: Even a half-metre rise could make most of Maldives uninhabitable; in the Solomon Islands, six islands disappeared between 1947 and 2014.

Saltwater intrusion: Tuvalu and Kiribati face salinisation of groundwater, damaging crops and drinking water.

Coastal erosion: Narrow beaches and reefs are shrinking, leading to displacement.

Socio-economic consequences

Food and water insecurity: Farming becomes harder as salt damages soil; fishing is hit by warming seas and acidification.

Economic losses: Tourism, agriculture, and fisheries — lifelines of island economies — are collapsing. The annual adaptation cost for small island states is estimated at $22–26 billion.

Infrastructure risks: In the Marshall Islands, a 1-metre rise may submerge up to 80% of its capital, Majuro.

Human displacement and cultural loss

Populations face becoming climate refugees losing homes and cultural heritage.

What island nations are doing

Tuvalu: Mean elevation about 2 metres. Facing repeated flooding, many Tuvaluans have applied for special migration options; under a recent agreement with Australia (Falepili Union), some Tuvaluans are being allowed to relocate each year. Over 4,000 applications for such visas were reported in 2025, showing how urgent the situation feels for residents. Tuvalu is also building artificial land and coastal defences to buy time.

Maldives: Has created and expanded Hulhumalé, an artificial island raised well above existing ground level to protect population and assets. The country is also pushing for global greenhouse gas cuts and seeking international finance for adaptation because much of its economy depends on tourism and beaches. Long-term sea level rise (projections up to about 0.9 m by 2100 in worst-case scenarios) would still be a severe threat without strong adaptation.

Kiribati: Bought a large tract of land in Fiji (2014) as a “plan B” in case relocation is needed. The purchase shows how island governments are trying both to protect land and to find options for their people.

Marshall Islands & others: Some islands build seawalls and raise beaches; the Marshall Islands have received funding for large coastal-protection works (for example projects around Ebeye). But engineering solutions can be expensive and sometimes temporary.

Sea-level rise is not a distant worry but a present crisis for island nations. It endangers their land, people, economy, and identity, making survival uncertain. The world must act on two fronts:

Without these, many small islands risk disappearing from the world map — along with unique cultures and histories.

|

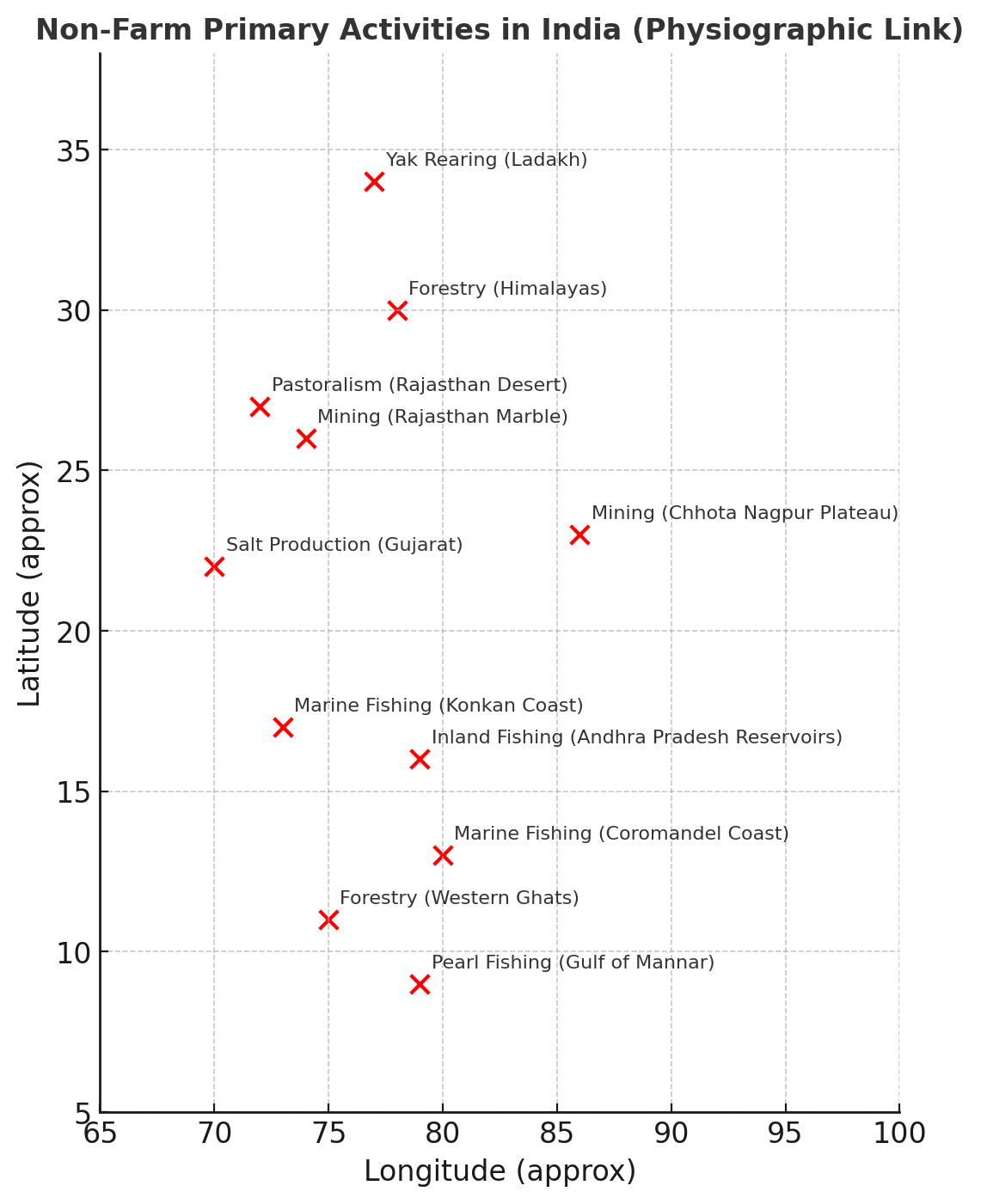

APPROACH Introduction → Cover the definition of non-farm primary activities and their dependence on natural resources and physiographic features in India. Body → Cover types of activities (fishing, forestry, mining, pastoralism), their physiographic links (coasts, forests, plateaus, deserts), and provide relevant regional examples for each. Conclusion → Cover the importance of physiography in shaping these activities and their role in sustaining rural livelihoods and the need for sustainable resource use. |

Primary activities are those that directly depend on natural resources. While agriculture (farming) is the most common, there are also non-farm primary activities like fishing, forestry, mining, quarrying, gathering, and pastoralism. These activities are deeply shaped by physiographic features — relief, soils, rivers, forests, coasts, plateaus, and climate. India’s diverse geography provides the base for a wide variety of such activities.

Activity |

Physiographic Link |

Examples |

|

Fishing |

Coastal areas, estuaries, rivers, and lakes |

Marine fishing: Konkan & Malabar coasts (nutrient-rich waters, upwelling currents), Coromandel coast, Gujarat coast Inland fishing: Ganga–Brahmaputra plains, reservoirs of Andhra Pradesh (India’s largest inland fish producer) |

|

Forestry and Gathering |

Mountain slopes, dense forests, tropical & subtropical regions |

Himalayan forests – deodar, pine, chir timber Central India (Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Jharkhand) – NTFPs like tendu leaves, mahua, lac Western Ghats – teak, rosewood, medicinal plants |

|

Mining and Quarrying |

Plateaus and mineral-rich regions |

Chhota Nagpur Plateau – coal, iron ore, mica Singhbhum (Jharkhand) – copper Rajasthan – marble, limestone, gypsum Kudremukh (Karnataka) – iron ore mining |

|

Animal Husbandry and Pastoralism |

Grasslands, arid zones, cold deserts |

Rajasthan desert – sheep & goat rearing (wool, meat) Ladakh & Sikkim – yak rearing (milk, wool, transport) Indo-Gangetic plains – cattle for milk (fodder availability) Himachal & Uttarakhand – transhumance (seasonal migration of Gujjars and Bakarwals) |

Other Non-Farm Primary Activities

Conclusion

ConclusionNon-farm primary activities in India highlight the close human–environment relationship. Physiography decides where fishing grounds, mineral belts, forest resources, and pastoral lands emerge. These activities sustain millions of people, often in remote or ecologically fragile areas. As India develops, the challenge is to ensure sustainable use of natural resources so that these traditional livelihoods continue without degrading the environment.

|

APPROACH Introduction → Define solar energy and highlight its growing importance in India’s energy mix for sustainable development. Body → Explain ecological benefits such as reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and pollution, and economic benefits including job creation, energy security, and cost savings with examples. Introduction → Summarize how solar energy supports India’s goals for clean energy transition and economic growth while protecting the environment. |

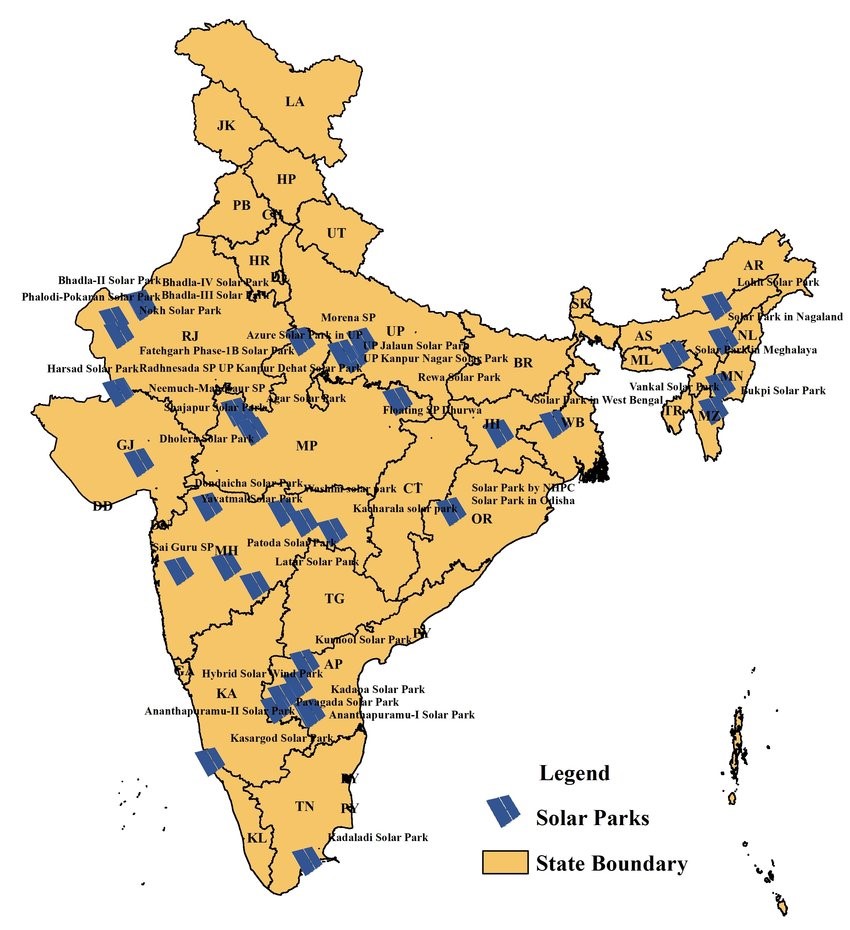

Solar energy has emerged as one of the fastest-growing renewable energy sources in India. It not only reduces dependence on fossil fuels but also contributes to climate goals, rural electrification, and green economic growth. India has set an ambitious target of 500 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2030, of which solar is expected to be the largest contributor.

As of January 2025, India’s installed solar capacity crossed 100 GW (81 GW ground-mounted, 17 GW rooftop, 2.8 GW hybrid, and 4.7 GW off-grid). In 2024 alone, India added 24.5 GW of new solar capacity—the highest ever in a single year. This scale-up reflects both ecological necessity and economic opportunity.

Mapping of established solar parks in India (approved/commissioned as per 31 march 2020).

Ecological Benefits

Reduction in Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Air and Water Quality Improvement

Land Reuse and Co-benefits

Support to Climate Commitments

Economic Benefits

Energy Security and Cost Savings

Job Creation and Rural Livelihoods

Boost to Manufacturing and Investment

Agriculture and Local Development

Global Leadership

Solar energy in India represents a synergy of ecological sustainability and economic growth. It lowers emissions, improves air quality, and conserves water while simultaneously creating jobs, boosting rural incomes, and enhancing energy security. With over 100 GW already installed and a 234 GW renewable pipeline under implementation/tendering, India is on track to transform its power sector.

To maximize benefits, India must ensure:

In sum, solar energy is not just a climate solution but also a foundation for a green, inclusive, and self-reliant economy.

|

APPROACH Introduction → Define tsunamis as large ocean waves caused by sudden disturbances like underwater earthquakes or volcanic eruptions. Body →How they are formed: Explain formation mainly by underwater earthquakes at tectonic plate boundaries causing seabed displacement, also by landslides, volcanic eruptions, or rare meteorite impacts. Where they occur: Mention common tsunami-prone areas near subduction zones like the Indian Ocean coast, Pacific "Ring of Fire", and specific vulnerable coastal regions. Consequences: Describe flooding, destruction of coastal infrastructure, loss of life, and environmental damage caused by tsunami waves. Examples: Give examples like the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami and 1883 Krakatoa eruption tsunami with their disastrous impacts. Conclusion→ Highlight the need for a multi-layered approach |

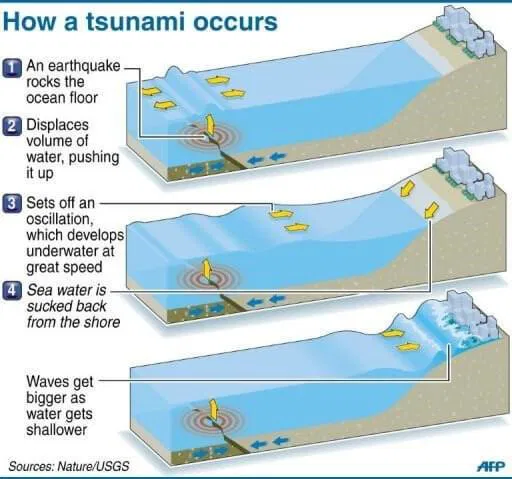

A tsunami is a series of very long ocean waves caused when a large volume of water is suddenly moved. The word comes from Japanese — tsu (harbour) + nami (wave). Tsunamis travel across oceans and can flood coasts, causing great loss of life and damage.

How are tsunamis formed?

Trigger (sudden disturbance): Most tsunamis start when something suddenly moves the sea floor or surface water — for example:

Even a small vertical shift over a very large area moves huge volumes of water and starts the waves.

Wave generation: The sudden displacement creates a train of waves that radiate outward from the source. In deep water these waves have very long wavelengths (sometimes hundreds of kilometres) and travel fast (up to 500–800 km/h), but with small height — so ships at sea may not notice them.

Wave shoaling (near the shore): As the wave enters shallower coastal water its speed drops and its height grows — the long wave is compressed, so the sea level can rise quickly and flood land. This is why deep-ocean tsunamis become deadly at coasts.

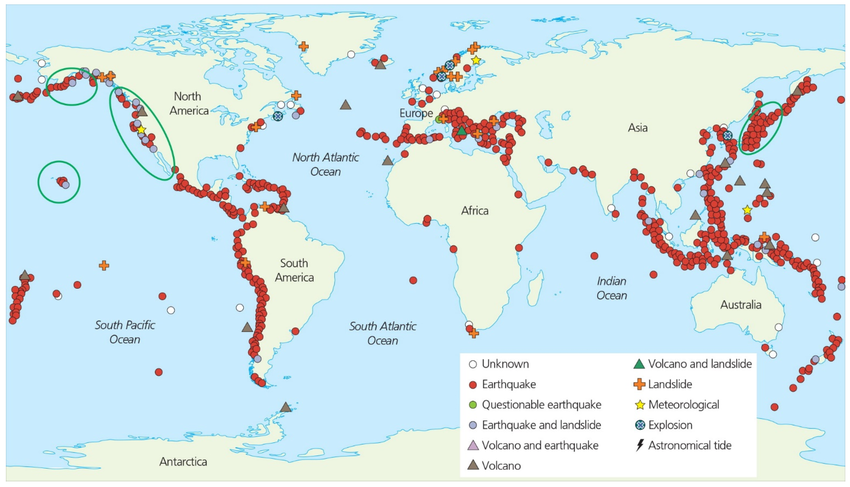

Where are tsunamis most likely to form?

Around subduction zones — places where one tectonic plate slides under another (for example: the Sunda Trench near Indonesia; the Japan Trench). These zones produce the biggest earthquakes (megathrust quakes) that can lift or drop the sea floor and cause massive tsunamis.

Volcanic island arcs — large volcanic eruptions (e.g., Hunga Tonga in 2022) can generate tsunamis.

Coastal cliffs and submarine slopes — underwater landslides (often earthquake-triggered) can also cause local tsunamis.

World map of historical tsunami sources, dating from 1610 B.C to A.D 2018.

Consequences of tsunamis (short-term and long-term)

Human and social impacts

Massive loss of life and injuries; example: the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami killed about ~225,000–230,000 people across many countries and displaced millions. Entire coastal communities were wiped out in places like Aceh (Indonesia), Sri Lanka, India and Thailand.

The 2011 Tōhoku tsunami (Japan) killed and went missing many thousands and caused a nuclear accident at Fukushima, showing how tsunamis can trigger second disasters.

Economic and infrastructure damage

Ports, roads, houses, fishing boats and tourism infrastructure get destroyed. Recovery can cost billions and take many years. (2004 and 2011 disasters resulted in very large economic losses.)

Environmental effects

Saltwater inundation destroys farmland, contaminates freshwater, and damages ecosystems (mangroves, coral reefs). Large amounts of debris and pollution may wash inland.

Psychological and long-term social effects

Survivors often face trauma, loss of livelihoods, migration, and long-term rebuilding challenges.

Warning systems and preparedness

After 2004, countries around the Indian Ocean set up tsunami warning systems. India’s Indian Tsunami Early Warning Centre (operated by INCOIS) monitors earthquakes and sea data 24×7, issues alerts, and works with coastal authorities to warn people. Community preparedness (evacuation plans, coastal zoning, mangrove restoration and public awareness) reduces loss of life.

Tsunamis, though rare, are among the most devastating natural hazards. They highlight the need for a multi-layered approach — combining early-warning systems, disaster-resilient infrastructure, community preparedness, and ecological safeguards. With India’s long coastline and rising coastal population, strengthening disaster risk reduction under frameworks like the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015–2030) and aligning with India’s National Disaster Management Plan is essential. Preparedness, not panic, is the key to saving lives and ensuring sustainable coastal development.

|

APPROACH: Introduction → Introduce the Smart Cities Mission as an urban development initiative aiming to improve quality of life through smart infrastructure and inclusive growth. Body → Explain how the mission targets urban poverty by improving housing, sanitation, and basic services, and promotes distributive justice by ensuring equitable access to resources and opportunities for all citizens. Conclusion → Summarize that the mission seeks to create sustainable, inclusive cities where benefits reach marginalized populations, reducing urban inequality. |

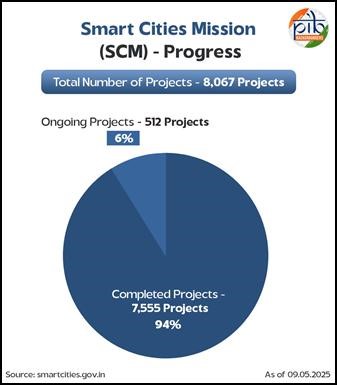

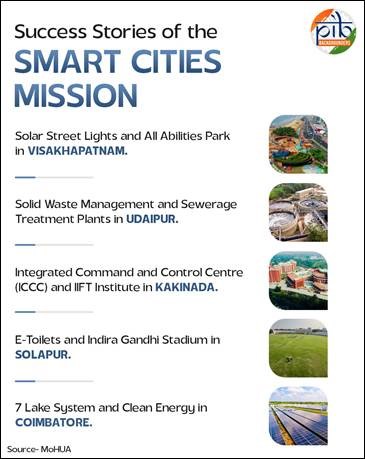

The Smart Cities Mission (SCM), launched in 2015, aimed to make selected Indian cities more liveable, sustainable and citizen-friendly by using technology and improving core services. While the mission mainly focuses on infrastructure, digital systems and service delivery, a key question for policy is whether these “smart” interventions help the urban poor and make access to opportunities fairer — i.e., advance distributive justice.

Scale and recent progress

The Mission covered 100 cities with projects funded from central, state and local sources and partnerships.

By early March 2025 about 7,500 projects (≈93%) were reported completed; only a small number of cities had finished all their projects by that date.

The overall investment mobilised (including state/ULB and private share) is reported around ₹1.5–1.64 lakh crore. These numbers show the Mission’s large scale but also uneven completion.

How Smart Cities tried to help the urban poor and distributional goals

Smart city projects had several channels that could reduce urban poverty or improve equity if implemented well:

a) Housing and slum rehabilitation (direct impact on the poor):

Many city proposals included in-situ slum redevelopment, affordable or EWS (economically weaker section) housing and rehabilitation. Cities such as Surat and parts of Pune/Maharashtra used smart-city and linked housing schemes to create thousands of affordable units or propose slum upgrading. When genuine in-situ redevelopment is done with secure tenure, services and nearby livelihoods, it directly improves poor households’ lives.

b) Basic services and public amenities (indirect but important): Projects like water supply, sewerage, public toilets, last-mile sanitation, street lighting, and solid-waste management improve daily life for the poor who often live in dense, service-deficient areas. Smart delivery (e.g., GIS maps, mobile grievance systems) can target service gaps more transparently.

c) Digital inclusion and government access: Integrated Command & Control Centres (ICCCs), online grievance portals, e-services and digital payments can help poor citizens access services faster, if they have digital access and skills. Several cities piloted participatory budgeting and digital platforms to involve citizens. Punehas a notable participatory budget mechanism that attempts to let people (including the marginalised) propose local projects.

d) Livelihood and public space improvements: Upgrading markets, bus terminals, pedestrian zones and skill-linking projects can protect informal livelihoods (street vendors, small traders) and make urban spaces safer for marginalized groups — again, only if policy protects their rights (for example, vending policies).

Evidence of success

Surat: Longstanding municipal affordable-housing and rehabilitation programmes were linked with smart-city area development; Surat claims large numbers of constructed houses for the urban poor and slum pockets given basic infrastructure. This shows smart projects can be used to scale up affordable housing where political will and municipal capacity exist.

Pune: Experiments in participatory budgeting and in-situ slum upgrading in areas like Yerawada show that when communities are engaged, projects can be more responsive to poor residents’ needs.

What went wrong

Despite pockets of success, several structural problems limited SCM’s impact on urban poverty:

a) Gentrification and dispossession:Slum redevelopment under the Mission was sometimes top-down and could dispossess people when surveys and beneficiary lists were poor. Civil-society reports document cases (e.g., parts of Ahmedabad, Bengaluru) where redevelopment plans risked evicting informal residents or reducing their access to livelihoods — turning “inclusive” projects into instruments of exclusion.

b) Misplaced priorities & cosmetic projects:Some cities spent money on visible “city-brand” infrastructure (façade projects, fountains, plazas) rather than on basic sanitation, affordable housing or livelihood protection. Local news reports from multiple cities show public anger where expensive projects did not help the poor.

c) Digital divide:Smart solutions assume internet access, smartphones and literacy. Poor households often lack these; thus digital delivery can bypass them unless specific digital-inclusion measures (free kiosks, community mobilisers) are provided.

d) Institutional continuity & funding gaps:The Mission officially ended in March 2025 and many Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs), ICCCs and projects face uncertainty. If maintenance and programme continuity are weak, benefits to the poor (who rely on public services) may vanish.

Policy lessons

The Smart Cities Mission has shown that technology and improved infrastructure can raise urban liveability. At the same time, its record on urban poverty and distributive justice is mixed: where cities linked smart interventions to affordable housing, slum upgrading and participatory governance (for example, Surat and parts of Pune), the poor gained; where projects were cosmetic, top-down or digital-only, the vulnerable were sidelined.

To realise distributive justice, urban policy must reorient smart investments toward pro-poor outcomes — secure housing, basic services, livelihood protection, digital inclusion and genuine community participation — and ensure institutional and financial continuity so benefits last. Only then will “smart” cities also be just cities.

|

APPROACH: Introduction → Explain that the ethos of Indian civil service combines professionalism (efficiency, neutrality, competence) with nationalistic consciousness (commitment to India’s unity, democracy, and development). Body → Discuss professionalism through merit-based recruitment, transparency, accountability, and efficient service delivery, and nationalistic consciousness through dedication to social justice, unity, disaster response, and nation-building initiatives with relevant examples. Conclusion → Conclude that this unique blend ensures civil servants act as efficient administrators and patriotic guardians of constitutional values, strengthening India’s democracy and inclusive development. |

Civil services in India are considered the “steel frame” of governance. The ethos of civil services means the guiding values, spirit, and character of officers in serving the nation. In India, this ethos combines professionalism (efficiency, neutrality, competence) with nationalistic consciousness (commitment to India’s unity, democracy, and development). This balance makes the civil service unique in addressing the country’s diverse challenges.

Professionalism in Civil Services

Nationalistic Consciousness

Examples & Initiatives

Challenges

Way Forward

The ethos of Indian civil services lies in blending professional competence with a spirit of nationalism and public service. As India aspires to become a developed nation by 2047, civil servants must not only act as efficient administrators but also as guardians of constitutional values, ensuring inclusiveness, justice, and equity. In this balance rests the real strength of India’s democracy.

|

APPROACH: Introduction → Explain globalization as the fast movement of people, goods, money, ideas, and culture, and introduce the debate about whether it results only in aggressive consumer culture or has wider effects. Body → Why globalization encourages consumer culture: Mention the rise of a large global consumer class, especially in Asia, global brands and e-commerce that standardize consumption, and media spreading lifestyles fueling consumerism. But globalization is not only aggressive consumerism: show how globalization also fosters cultural exchange and hybridization, creates economic opportunities and poverty reduction, and spreads political and social ideas. Negative side-effects beyond consumerism: List concerns like inequality, environmental damage, and cultural commodification resulting from increased consumption and globalization. Examples that show the mixed picture: Use examples like McDonald’s and Netflix (consumer culture), K-pop and Indian cinema (cultural exchange), India's growing consumers (local entrepreneurship), and local resistance/regulation to show the complex reality. Conclusion → Conclude that globalization promotes both consumer culture and multiple other social, economic, and cultural effects, and that managing globalization to maximize benefits while minimizing harms is essential. |

Globalization means people, goods, money, ideas and culture moving faster across countries. It has certainly spread brands, malls and online shopping — which many call an “aggressive consumer culture.” But to say globalization results in only that would be wrong. Globalization produces many effects at once — some encouraging consumption, others spreading culture, technology, jobs and ideas, and still others creating resistance and regulation.

Why globalization encourages consumer culture

Bigger global consumer class: The world reached about 4 billion consumers in 2023, and Brookings estimates the consumer class will grow further — Asia (especially India and China) will add most new consumers. This large and growing consumer base fuels demand for brands, gadgets and services.

Global brands and new shopping channels: Multinational brands (McDonald’s, Nike, Coca-Cola) and global e-commerce platforms (Amazon, Alibaba) standardise tastes and make buying easier — encouraging frequent, brand-centred consumption. The spread of integrated digital payments and online retail (rapid growth noted by consumer studies such as McKinsey’s State of the Consumer) accelerates buying behaviour.

Media and cultural influence: Global streaming (Netflix), social media and advertising transmit lifestyles and status symbols widely; many people adopt global styles, food habits, and fashion — a visible sign of consumer culture. Sociologists call this effect “McDonaldization” or cultural homogenization.

But globalization is not only aggressive consumerism

Cultural exchange and hybridisation: Globalization also spreads music (K-pop, Bollywood), food, ideas and languages, producing hybrid cultures — not just copies of Western consumerism. Many societies adapt foreign elements and create new local forms. Britannica and cultural studies emphasise both homogenising and hybridising outcomes.

Economic opportunities and poverty reduction: Global trade and investment have lifted millions out of poverty by creating jobs in manufacturing, services and tech. Even though FDI and trade flows have seen recent slowdowns, UNCTAD and World Bank data show that global investment and integration remain key drivers of employment and rising incomes in many countries. (UNCTAD reported global FDI flows around $1.3 trillion in 2023.)

Political and social ideas cross borders: Globalization spreads human-rights norms, environmental movements, and governance ideas. Examples: the global climate movement, international labour standards, and cross-border NGOs that press for social justice. These are not consumer culture.

Negative side-effects beyond consumerism

Inequality and ecological cost: Growth of consumption often increases inequality (luxury vs. poor) and environmental stress (higher emissions, waste). Recent research links globalization and higher resource use and GHG emissions in many contexts. The global rise in consumption strains planetary boundaries.

Cultural loss and commodification: Some local traditions become commercialised; tourism and markets can turn culture into a product, weakening deeper meanings. Critics warn about cultural homogenization and loss of local diversity.

Examples that show the mixed picture

Globalization has certainly fuelled a powerful consumer culture — larger markets, global brands, and new technologies make buying easier and lifestyles more similar across countries.

But it is not only an aggressive consumer culture. Globalization also spreads ideas, creates jobs, enables cultural mixing, and generates political and regulatory responses that check or reshape consumption.

The real picture is mixed: consumerism is a strong strand of globalization, but other strands — cultural exchange, economic opportunity, environmental costs and local resistance — run alongside it. Policy-makers should therefore manage globalization so its economic and cultural benefits reach most people while limiting inequality, cultural erosion and environmental harm.

|

APPROACH: Introduction → Briefly introduce Mahatma Jotirao Phule as a pioneering social thinker whose writings and reformist activities systematically challenged caste, patriarchy, and economic exploitation, positioning him as a voice of the oppressed subaltern classes. Body → Explain how his writings (like Gulamgiri and essays) gave ideological clarity to Dalits, Shudras, women, and peasants; show how his reform efforts (schools for girls and lower castes, Satyashodhak Samaj, widow-remarriage, shelters for women, critique of landlords and moneylenders, cultural reform) directly supported these groups; and highlight the intellectual legacy and limitations of his impact. Conclusion → Conclude that Phule was a pioneer whose holistic work — both ideological and practical — laid the foundation for later anti-caste, feminist, and farmer movements, ensuring his reform touched almost all subaltern classes in India’s modern social justice journey. |

Mahatma Jyotirao (Jotiba) Phule (1827–1890) was a social thinker and activist from Maharashtra. He attacked the caste system, fought for women’s education and rights, and worked for the poor and peasants. His importance lies in two connected things: his writings (books and pamphlets that explained why society was unjust) and his practical reforms (schools, institutions and a social movement). Together these touched the lives of many “subaltern” groups — women, Dalits/untouchables, Shudras, peasants and urban labourers.

Writings

Major writings and their themes

Gulamgiri (Slavery, 1873) — Phule compared caste oppression to slavery and argued that Brahmanical rules kept many people in social and economic bondage. He showed caste was a system created to keep some people poor and powerless.

Other pamphlets and essays — Phule wrote on women’s rights, on how priests and ritual reinforced inequality, and on the cruel effects of caste on ordinary life. His collected writings were later published and translated so activists could use his ideas.

Clear language that spoke to the oppressed

Phule wrote plainly and used everyday examples. He did not only argue in abstract terms — he pointed out how caste stopped children from going to school, how rituals supported landowners and moneylenders, and how women suffered because of child marriage and widowhood. This made his ideas useful to people suffering those problems.

How writings reached different subaltern classes

Dalits / Untouchables: Gulamgiri named the injustice they faced and argued they were not naturally low but oppressed by an ideology. This gave leaders and ordinary people words to describe their suffering.

Shudras and peasants: Phule linked caste with economic exploitation. He showed how ritual and caste rules helped landlords and moneylenders extract surplus from peasants. This connected caste critique to material problems of farmers.

Women: His writings called for women’s education and for ending practices that harmed women. By combining criticism of caste with criticism of patriarchal customs, Phule spoke to both poor and upper-caste women who were hurt by social rules.

Intellectual impact and legacy from writings

Phule’s books became reference points for later thinkers (for example Dr B.R. Ambedkar and many anti-caste activists). His critique helped convert private suffering into public questions: “Who benefits from caste?” and “How do institutions keep people poor?” This made social reform an argument, not just charity.

Social-reform efforts

Education

Satyashodhak Samaj 1873

Direct help to women and children

Mobilising peasants and criticizing economic oppression

Cultural and ritual reform

Limitations

Phule was not just a reformer of his time but a pioneer of anti-caste thought, a forerunner of feminist ideas, and an early voice for farmers’ rights. His work laid the intellectual and organisational foundation for the 20th-century Dalit movement, women’s emancipation efforts, and the idea of Bahujan (majority) empowerment. Therefore, it is fair to say that Phule’s efforts truly touched almost every subaltern class and planted the seeds of modern India’s struggle for equality and social justice.

|

APPROACH: Introduction → Briefly introduce Mahatma Jotirao Phule as a pioneering social thinker whose writings and reformist activities systematically challenged caste, patriarchy, and economic exploitation, positioning him as a voice of the oppressed subaltern classes. Body → Explain how his writings (like Gulamgiri and essays) gave ideological clarity to Dalits, Shudras, women, and peasants; show how his reform efforts (schools for girls and lower castes, Satyashodhak Samaj, widow-remarriage, shelters for women, critique of landlords and moneylenders, cultural reform) directly supported these groups; and highlight the intellectual legacy and limitations of his impact. Conclusion → Conclude that Phule was a pioneer whose holistic work — both ideological and practical — laid the foundation for later anti-caste, feminist, and farmer movements, ensuring his reform touched almost all subaltern classes in India’s modern social justice journey. |

After gaining independence in August 1947, India faced the enormous challenge of transforming from a fragmented colony into a unified, democratic, modern nation. The leadership of the time—especially Jawaharlal Nehru and Sardar Patel—focused on consolidating the country across different dimensions: political, economic, educational, and international. This period (roughly 1947–1964) laid the foundations for India’s future growth and stability.

Body

Polity

Economy

Education

International Relations

India’s early post-independence years (1947–1964) marked a transformative journey from a fractured colonial territory to a functioning democratic nation. Under the leadership of Nehru, Patel, and others, the country achieved political unity through the integration of princely states, a robust constitutional structure, and successful elections. Economic foundations were laid with state-led planning, infrastructure projects, and industrial policy. Education reforms fostered human capital via commissions and the establishment of premier institutions. On the world stage, India asserted itself through non-alignment, Panchsheel, and global engagement.

Critically, these efforts were not isolated: they were interlinked—political stability enabled economic planning, which supported educational expansion, which in turn strengthened India’s diplomatic stature. Together, they built a resilient architecture for nation-building. Despite challenges—low growth, bureaucratic hurdles, and regional disparities—the consolidation process of that period created the durable pillars of India’s democracy, economy, society, and global identity.

|

APPROACH: Introduction → Briefly introduce Mahatma Jotirao Phule as a pioneering social thinker whose writings and reformist activities systematically challenged caste, patriarchy, and economic exploitation, positioning him as a voice of the oppressed subaltern classes. Body → Explain how his writings (like Gulamgiri and essays) gave ideological clarity to Dalits, Shudras, women, and peasants; show how his reform efforts (schools for girls and lower castes, Satyashodhak Samaj, widow-remarriage, shelters for women, critique of landlords and moneylenders, cultural reform) directly supported these groups; and highlight the intellectual legacy and limitations of his impact. Conclusion → Conclude that Phule was a pioneer whose holistic work — both ideological and practical — laid the foundation for later anti-caste, feminist, and farmer movements, ensuring his reform touched almost all subaltern classes in India’s modern social justice journey. |

The French Revolution (1789–1799) was a turning point in world history that dismantled monarchy and feudal privileges, replacing them with ideas of liberty, equality, fraternity and popular sovereignty. These ideas became the foundation of modern democracy, human rights, and social justice—concepts that continue to influence the contemporary world.

Body

Universal Ideals of Liberty, Equality & Fraternity

Popular Sovereignty & Democratic Governance

Legal Reforms & Rule of Law

Secularism & Separation of Church and State

Social Justice & Feminist Movements

Nationalism & Anti-Colonial Struggles

The French Revolution was not just an event in French history but a blueprint for modern democracy and justice. Its core ideals continue to guide constitutions, human rights charters, social justice campaigns, and global protest movements. From climate justice protests (Fridays for Future) to pro-democracy uprisings (Hong Kong, Belarus), the revolutionary spirit still inspires people worldwide to challenge oppression and demand a just, inclusive, and equitable order.

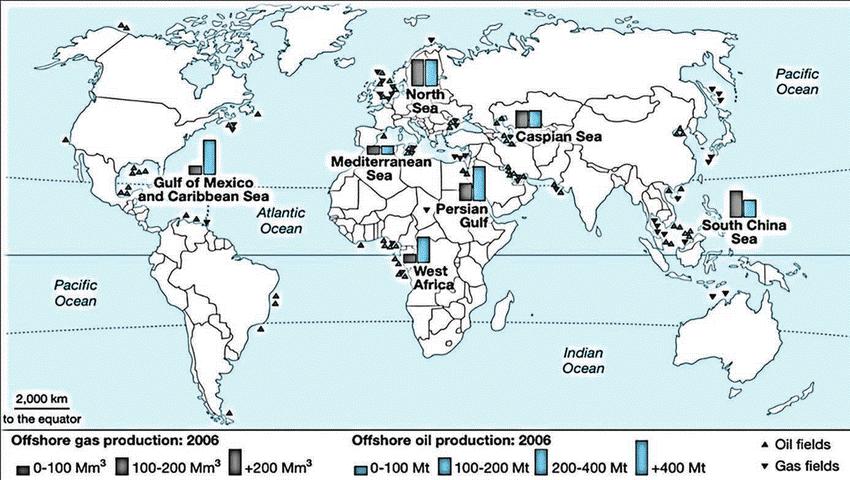

Offshore oil reserves are hydrocarbons trapped beneath the seabed along continental margins, in inland seas and in some inland (lacustrine) basins. Today a large and growing share of global conventional oil production comes from offshore fields — from shallow continental shelves to ultra-deepwater and pre-salt basins. The location of these reserves is controlled by long-term geological processes (basin formation, sedimentation and burial), and by the later migration and trapping of oil and gas.

Why offshore oil occurs where it does

Location on continental margins and marine sedimentary basins

Location on continental margins and marine sedimentary basins

Most offshore hydrocarbon systems are found on passive and active continental margins — places where thick layers of sediment accumulated in marine basins (e.g., Atlantic passive margins, Gulf of Mexico margin). These sediments include organic-rich source rocks that, after burial and heating, generated oil and gas. Marine basins concentrate the right conditions (burial, heat, sediment) for petroleum systems.

Rift and passive-margin basins (turbidites and submarine fans)

Many prolific offshore reservoirs are deepwater turbidite sands deposited on continental slopes and fans (e.g., Niger Delta deepwater, Brazil’s pre-salt turbidites). These reservoirs can be laterally extensive and hold large volumes of oil.

Salt tectonics & pre-salt carbonate plays

In places like offshore Brazil (Santos and Campos basins), thick salt layers created special traps: hydrocarbons formed beneath the salt (“pre-salt”) and were preserved in lacustrine carbonates and sands. Salt creates structural traps by moving and deforming overlying sediments.

Foreland basins and deltaic systems

Deltas and adjacent slope areas (e.g., Gulf of Mexico, Niger Delta, West Africa) collect organic-rich sediments and later develop deepwater extensions that are rich in hydrocarbons. Oil migrates from buried source rocks into reservoir sands and gets trapped in structural and stratigraphic traps.

Historic sea-level and paleogeography effects

Areas that were once shallow seas or large lakes in geological past (lacustrine basins) may host significant offshore reserves today because the ancient conditions were ideal for organic accumulation and preservation.

Where offshore oil is concentrated

How offshore occurrences differ from onshore occurrences

|

Aspect |

Offshore Occurrences |

Onshore Occurrences |

|

A. Geological Differences |

Found in marine sedimentary basins along continental margins, deepwater fans, submarine channels, and sub-salt basins. Reservoirs often include turbidite sands, channel complexes, and sub-salt carbonates. |

Found in intracratonic basins, foothill/foreland basins, fluvial/deltaic or carbonate settings. Reservoirs include fluvial sandstones, carbonate platforms, and fractured basement. |

|

B. Exploration & Trapping Complexity |

Complex traps created by salt tectonics (large structural pre-salt traps, deepwater turbidite stratigraphic traps). Seismic imaging benefits from modern marine seismic but faces challenges under salt and in deepwater. |

Simpler structural traps (domes, anticlines) or stratigraphic pinchouts. Seismic imaging is generally easier in many basins. |

|

C. Technical & Engineering Differences |

Drilled from platforms, drillships, subsea systems (fixed, jacket, floating). Requires complex riser systems in deep water. Production often needs subsea tiebacks, or long pipelines to shore. |

Drilled using land rigs — logistically simpler. Production uses well pads, short pipelines, and nearby refineries. |

|

D. Economic Differences |

Highly capital-intensive and expensive per well/tonne. Higher break-even prices and longer project lead times. Offshore fields can be very large, making them attractive despite high upfront cost (e.g., Brazil pre-salt, Gulf of Mexico deepwater). |

Relatively cheaper per well/tonne. Lower project lead times and break-even costs. Field sizes can vary but are often smaller than offshore giant fields. |

|

E. Environmental & Risk Differences |

Offshore spills have wide marine impact, are difficult to contain, and clean-up is complex. Deepwater blowouts pose major risk (e.g., past incidents like Deepwater Horizon). Remoteness complicates response efforts. |

Impacts are mostly local (soil, groundwater contamination), easier to access and remediate compared to offshore. |

|

F. Legal & Jurisdictional Differences |

Governed by maritime law (UNCLOS) – territorial sea, EEZ, continental shelf jurisdiction. Disputes over maritime boundaries can delay exploration and production. |

Governed by national/domestic laws, jurisdiction is clear with no cross-border legal complexity. |

Implications

Offshore oil reserves, concentrated along passive continental margins, deepwater fans and sub-salt basins now contribute nearly a third of global crude production.

Unlike onshore reserves, they are geologically more complex, technologically demanding, and cost-intensive, requiring advanced seismic imaging, deepwater drilling, and subsea production systems. Their development is not just a technical challenge but also a geopolitical and environmental consideration, as many lie in disputed maritime zones and are vulnerable to climate-change-driven extreme events.

With the global energy transition under way, offshore reserves will remain crucial in bridging energy demand while pushing the world towards cleaner fuels like natural gas, but their exploitation must balance economic viability with sustainability and risk mitigation.

In India, major offshore fields like Mumbai High and KG Basin contribute significantly to domestic crude and natural gas output, and policies like the Open Acreage Licensing Policy (OALP) aim to accelerate deepwater exploration to reduce import dependence.

|

APPROACH: Introduction → Explain how AI, drones, GIS, and Remote Sensing together form a data-driven toolkit for efficient locational (siting) and areal (management) planning by combining information gathering, analysis, and visualization. Body → Describe roles of each technology (RS for wide coverage, drones for local detail, AI for automated analysis, GIS for integration), show how they work together (data collection, AI classification, GIS mapping), and illustrate applications in urban planning, land-use zoning, disaster management, agriculture, and conservation, along with benefits (speed, accuracy, transparency) and challenges (skills, costs, privacy). Conclusion → Conclude that integrating AI, drones, GIS, and RS enables predictive, transparent, and sustainable planning, transforming development and disaster preparedness, provided legal, technical, and human capacity challenges are addressed. |

Artificial Intelligence (AI), drones (UAVs), Remote Sensing (RS) and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) together form a powerful toolkit for locational (where to put something) and areal (how to manage an area) planning. Put simply: satellites and drones collect pictures and data, AI turns that data into useful information (like maps or predictions), and GIS helps planners see and use that information on maps to make better choices.

What each technology does

Remote Sensing (RS): Satellites or airborne sensors that take pictures of the Earth (large-area view).

Drones: Small flying cameras that give very detailed pictures of a local area (fine-scale, quick).

AI (Machine Learning / Deep Learning): Computers that learn to recognise patterns in images and data — for example, finding buildings, roads, crops or flooded zones automatically.

GIS: Software that puts all these layers (maps, pictures, rules, statistics) together so planners can see where things are and make decisions.

How they work together

Collect data: satellites give frequent wide-area images; drones give very sharp local images; sensors and field surveys give ground truth.

Process with AI: algorithms classify land use (farm, forest, built-up), detect objects (buildings, roads), and spot changes over time (new construction, erosion).

Integrate in GIS: results are shown as map layers (where is suitable land, where is risky, what service reaches where). Planners use these maps to pick sites and design zones.

Uses in locational and areal planning

Urban planning and infrastructure siting

Where to put a school, hospital or road? Use satellite + drone maps to check land use, slope, flood risk and distance to population; AI speeds up identifying empty plots and building footprints.

Land-use and zoning decisions

Classifying land (farmland, forest, built-up) using AI trained on satellite and drone images helps create accurate zoning maps for cities and districts. This avoids mistakes like building on agricultural land or wetlands.

Disaster risk reduction and emergency planning

Floods, earthquakes, cyclones: satellite imagery gives the big picture, drones map damaged areas quickly, AI detects blocked roads or collapsed buildings, and GIS helps route relief teams and shelters.

Agriculture and watershed planning

Crop health, irrigation, soil moisture: satellites and drones monitor fields; AI estimates crop stress and yield; GIS helps plan irrigation and drought-response by mapping vulnerable zones. This supports areal planning for food security.

Environment, forests and water bodies

Surveying and conservation: drones and satellites detect encroachment, illegal mining or shrinking lakes. State programmes now use drone surveys to map lakes and protect water bodies — saving time and improving accuracy.

Benefits

Challenges

|

CASE STUDIES Real-world examples

Indian Examples Karnataka

National SVAMITVA scheme

Arunachal floods

|

Effective use of AI, drones, GIS, and Remote Sensing can transform locational and areal planning from a reactive exercise into a data-driven, predictive, and participatory process.

These technologies ensure speed (real-time data capture), precision (high-resolution mapping), and inclusivity (transparent and shareable GIS layers) in decision-making. For India, this means better-planned cities, scientifically zoned rural areas, climate-resilient infrastructure, and faster disaster response.

Going ahead, success will depend on capacity building of local planners, open data standards, and clear legal frameworks for drone operations and AI use. When integrated thoughtfully, these tools will not just answer where to build and how to manage land, but also help foresee future risks — making planning sustainable, equitable, and future-ready.

|

APPROACH: Introduction → Define tectonic plates and state that their constant movements cause long-term changes in the shape and size of continents and ocean basins. Body → Explain mechanisms such as seafloor spreading (ocean widening), subduction (ocean shrinking), continental rifting (splitting of landmasses), continental collision (mountain building), and transform faults (lateral shifts); illustrate with examples like the Atlantic Ocean opening, Himalayan uplift, and East African Rift; and support with evidence (magnetic stripes, GPS data, fossil distribution). Conclusion → Conclude that though slow, tectonic plate movements continuously reshape Earth, creating new oceans, mountains, and landforms, and are the driving force behind the dynamic nature of continents and ocean basins. |

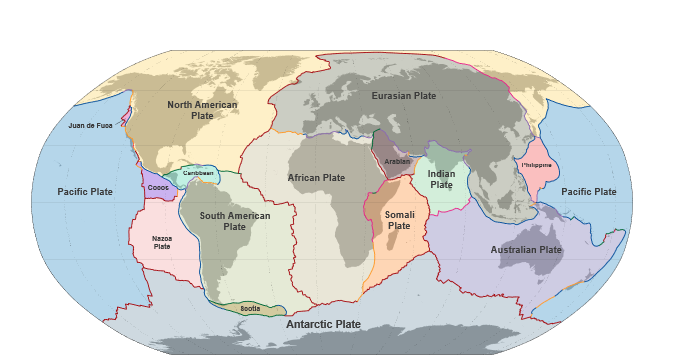

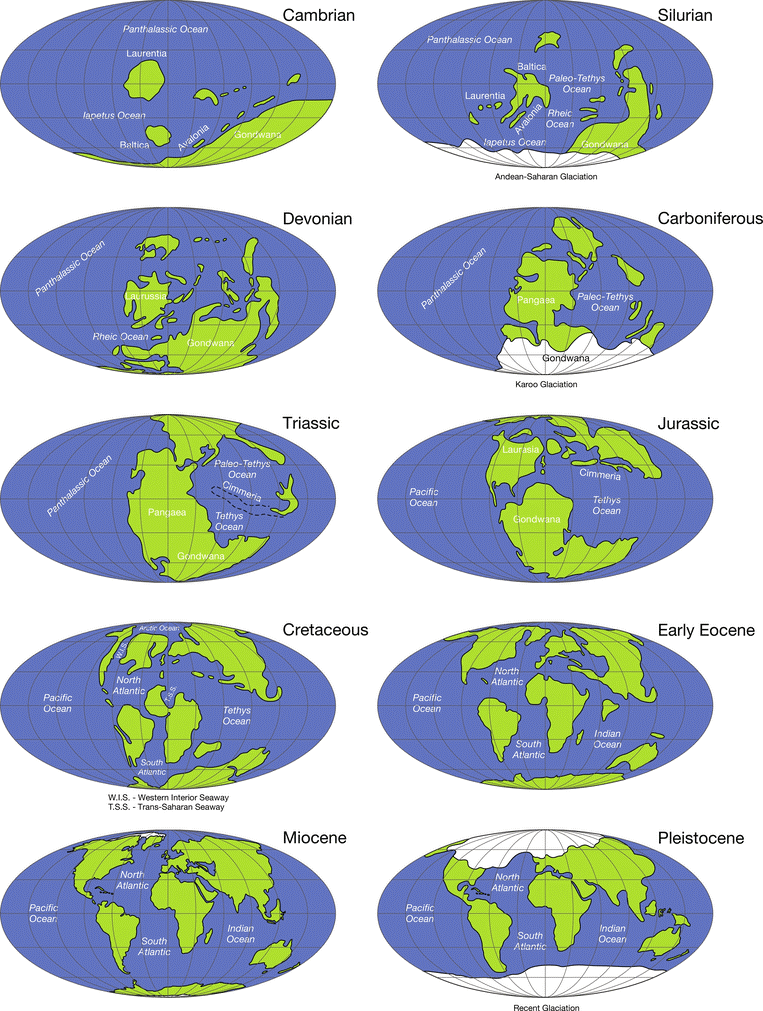

The outermost layer of the Earth — the crust and the upper mantle — is broken into large pieces called tectonic plates. These plates slowly move on the softer layer beneath them. Because of these plate movements, the shapes and sizes of continents and ocean basins change over millions of years. This movement makes mountains grow, oceans open and close, and new land form or disappear.

How plates move

Seafloor spreading (mid-ocean ridges): At mid-ocean ridges (like the Mid-Atlantic Ridge), magma rises from below and makes new oceanic crust. The new crust pushes older crust away on both sides, so the ocean basin grows wider. The Mid-Atlantic Ridge spreads at about 2.5 cm per year (≈ 25 km per million years). Over tens of millions of years this adds up to large changes in ocean size.

Subduction (ocean disappears): Where an ocean plate meets a continental plate, the denser ocean plate sinks under (is subducted) into the mantle. This destroys old ocean floor and can make deep ocean trenches and volcanic mountain chains (for example, the Andes). Because old ocean floor is recycled, very little ocean crust is older than about 150 million years.

Continental rifting (continents split): Sometimes a continent begins to pull apart. A long valley (rift) forms, volcanoes may appear, and eventually a new ocean can form between the split pieces. The East African Rift is a real example that has been forming for about 30 million years and may become a new ocean in the distant future.

Continental collision (mountain building): When two continental plates meet, they push against each other and the crust thickens and rises into mountains (because continental crust is too light to sink). The India–Asia collision pushed up the Himalaya and began when India moved north and hit Eurasia tens of millions of years ago. At times India moved unusually fast — estimates around ~20 cm/year during part of its northward journey — which helped create the great Himalayan range.

Transform faults (sliding past): Plates can also slide sideways past each other (e.g., the San Andreas Fault in California). This changes shapes locally and causes earthquakes, but does not make or destroy ocean floor the way spreading and subduction do.

Examples that show how shapes and sizes change

Evidence

Paleogeographic reconstructions of major continents and oceans throughout Earth history from the Cambrian to Pleistocene.

Changes in the shapes and sizes of continents and ocean basins happen because Earth’s outer shell is split into moving tectonic plates. The plates make new crust at mid-ocean ridges, destroy crust at subduction zones, pull continents apart at rifts, and push them together at collisions.

These processes work very slowly — millimetres to centimetres per year — but over tens to hundreds of millions of years they reshape the face of the planet: oceans open and close, mountain ranges rise, and continents drift. Real examples—the Atlantic opening, the Himalaya forming, and the East African Rift—help us see these long-term changes in Earth’s crust.

|

APPROACH: Introduction → Introduce the Ganga River Basin as India’s largest and most populous river basin, highlighting its geographical extent, population significance, and agricultural contributions as the foundation of Indian civilization. Body → Explain population distribution and density patterns (upper, middle, lower basin variations), link land and soil resources (alluvial fertility, double cropping) with settlement, describe water resources (surface water, canals, monsoon dependence) and their role in supporting agriculture and habitation, and discuss settlement patterns including urban centers, rural clustering, and flood-prone areas. Conclusion → Conclude that while the Ganga Basin is India’s cultural and economic lifeline, sustaining nearly half the population, it faces severe resource pressures, making integrated, sustainable river basin management essential for long-term ecological and human security. |

The Ganga River Basin is the largest river basin in India and one of the most populous in the world. It covers an area of about 8.6 lakh km² (26% of India’s geographical area) and spans 11 states including Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Haryana, Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh, and Delhi. The basin supports over 500 million people—nearly 43% of India’s population—and contributes nearly 40% of the country’s total agricultural output. Its fertile alluvial plains, perennial river system fed by Himalayan glaciers and monsoon rains, and extensive canal network have made it the heartland of Indian civilization since ancient times.

Population Distribution & Density

Land and Soil Resources

Water Resources

Patterns of Settlement

The Ganga River Basin is not just a physical region but the economic and cultural lifeline of India. Its abundant land, fertile soils, and perennial water supply have made it the cradle of Indian civilization and the most densely populated river basin globally.

However, this very concentration of population exerts immense pressure on resources, leading to issues such as over-extraction of groundwater, water pollution, frequent floods, and soil degradation.

For sustainable development, there is a need for integrated river basin management — combining efficient irrigation, pollution control (Namami Gange mission), floodplain zoning, and climate-resilient agriculture — to balance human needs with ecological health and ensure that this vital basin continues to support nearly half of India’s population in the future.

|

APPROACH: Introduction → Highlight India’s rapid rise in lifestyle diseases (diabetes, obesity, hypertension) linked strongly with ultra-processed food (UPF) consumption, framing the fast-food industry boom as both an economic and public-health challenge. Body → Explain scale and growth of Quick Service Restaurants, cloud kitchens, and UPF sales, and identify major drivers (urban lifestyle, rising incomes, digital delivery platforms, marketing, affordability, taste engineering); show why fast food prevails despite health risks (convenience, low cost, consumer ignorance, weak regulation, industry incentives); mention emerging healthier alternatives and startup-driven innovations. Conclusion → Conclude that India faces a market-failure where private sector incentives conflict with public health, requiring stronger regulation, fiscal measures, accountability of food platforms, public education, and support for healthier innovations to balance economic growth with long-term health goals. |

India now faces epidemic levels of diabetes, obesity, and hypertension: nearly 11.4% of Indians have diabetes, 28.6% are obese, and 35.5% have elevated blood pressure.

Since 1995, lifestyle disease burden has tripled, and over 56% of the total disease burden is attributable to junk food.

A 2024 BMJ meta-analysis linked ultra-processed food intake to 32 serious health issues including various cancers, type-2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, mental health disorders, and premature death.

The combination of lifestyle disease spread and inadequate regulation is straining healthcare and productivity—yet fast-food consumption continues to rise.

Scale

The organised Quick Service Restaurant (QSR) market in India is estimated at about USD 27.8 billion in 2025, with projected continued growth.

The cloud-kitchen market — a delivery-only model that reduces entry barriers — was valued at roughly USD 1.1–1.3 billion in 2024 and is projected to grow at double-digit CAGRs (≈13–17% range) over the next decade.

Retail sales of Ultra Prcoessed Foods (UPFs) in India grew rapidly over the 2010s; WHO-India/market analyses reported ~13% CAGR in UPF retail sales between 2011–2021, signalling deepening market penetration including in smaller towns.

Drivers of Fast Food Growth in India

Urban Lifestyle & Time Pressures

Many Indians face long commutes and busy work schedules. This, along with the shift from joint families to nuclear ones, means cooking from scratch is less feasible—making fast or packaged food a practical choice.

Rising Incomes & Changing Aspirations

With more disposable income, consumers are willing to spend on convenience and novelty. The fast-food sector—both global chains and local quick-service brands—is expanding across metros as well as Tier-2 and 3 cities.

Digital Transformation

Services like Zomato and Swiggy have made fast food just a tap away. Coupled with cloud kitchens, they’ve made delivery of hot food easier, even in smaller towns.

Localization & Innovation by Chains

International brands adapt to Indian tastes e.g., McDonald’s, offer value meals and reach deeper into non-metro markets.

Addictive 'Hyper-Palatability' & Aggressive Marketing

Fast foods are engineered to be irresistibly savory, salty, or sweet. Ingredients and flavor science hijack our brain's reward systems, often leading to overconsumption. Aggressive, aspirational marketing—alluring to youth—adds fuel to the fire.

Why Fast Food Keeps Winning Despite Health Risks

Convenience Trumps Caution

Immediate availability and time-saving delivery often outweigh long-term concerns about health.

Affordability & Accessibility

Value pricing, proliferation of outlets, and delivery infrastructure make fast food affordable and omnipresent.

Marketing & Youth Appeal

Brands use localized products, promotions, and social media to attract young urban consumers who value novelty and taste.

Weak Regulatory Environment

Though FSSAI has strengthened labeling and compliance frameworks (annual amendment enforcement date; labelling regulations updated), enforcement at the retail and digital order level remains uneven. Food marketing to children and point-of-sale restrictions are partial or patchy.

Asymmetric information & weak behaviour change

Long-term harms (diabetes years later) do not deter short-term choices unless consumers are adequately informed and motivated. Nutrition literacy remains limited.

Economic incentives favour industry

Investors, suppliers and app platforms have strong commercial incentives to expand reach and lower prices — often at the cost of nutritional quality.

Supply chain transformation

Industrial food processing, economies of scale and standardized inputs keep UPFs cheap and consistent, encouraging consumption across socio-economic groups.

Signs of Shift

Health-Oriented Food Startups

Brands like Farmley, Yoga Bar, and SuperYou are gaining traction—fuelled by wellness trends, higher incomes, and quick-commerce platforms.

Protein-Enriched Offerings

In a country with widespread protein deficiency (~73%), food chains are innovating. McDonald’s launched a vegetarian protein slice in South India that sold 32,000 units in 24 hours.

The sustained expansion of India’s fast-food and ultra-processed food sector — driven by urbanisation, digital platforms, value pricing and aggressive marketing — has outpaced public-health countermeasures.

The result is a classic market-failure problem: private incentives to sell inexpensive, palatable, processed foods diverge from the social goal of good nutrition and NCD prevention. To reconcile economic growth in the food services sector with public health, India needs a multi-pronged, evidence-based strategy:

If implemented together, these measures can preserve the convenience and employment benefits of the fast-food industry while reducing its long-term costs to public health and the economy.

|

APPROACH: Introduction → Define sustainable growth as balancing environmental protection with economic needs, and highlight that in India large numbers of poor people depend directly on natural resources, making conflicts likely. Body → Explain why conflicts arise (resource dependence of poor, short-term survival vs. long-term benefits, conservation-linked displacement, energy transition job losses); illustrate with examples of dams, mining, forest projects, and pollution norms affecting livelihoods; then show how environmental measures can also support livelihoods (MGNREGA 2.0, solar, eco-tourism, organic farming); and propose reconciliations like just transitions, community rights, green jobs, safety nets, and participatory conservation, drawing from Indian and global best practices. Conclusion → Conclude that while achieving sustainable growth can conflict with poor people’s needs, the solution lies in an integrated, just transition approach that combines ecological protection with livelihood security so that sustainability is both social and environmental. |

Sustainable growth means growing the economy while protecting the environment so people today and tomorrow can live well.

As of 2022-23, India's poverty rate at the $3.65 per day line stood at 28.1%, indicating that approximately 378 million people live in poverty. Rural poverty has declined from 69% in 2011-12 to 32.5% in 2022-23, while urban poverty dropped from 43.5% to 17.2% during the same period.

Many of these individuals rely directly on natural resources—such as forests, rivers, and land—for their livelihoods. For instance, tribal communities in forested regions depend on forest produce for food, medicine, and income. Restrictions on forest access for conservation purposes can, therefore, threaten their survival.

The issue is not only theoretical: examples from mining, forest conservation and energy transitions show real conflicts between protecting nature and protecting incomes. Any answer must balance environmental goals (clean air, forests, biodiversity, climate action) and poverty-reduction goals (jobs, food, shelter, energy access).

Why conflicts arise

Resource dependence of the poor: Millions of poor people live in rural and forested areas and depend on land, fuelwood, grazing, small farming and fishing for daily survival. When an area is protected (park, reserve) or when mining/large projects take land, these livelihoods are disrupted. For example, mining and coal projects have historically displaced tens of thousands in mineral belts like Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh.

Short-term survival vs long-term benefit: Poor households need income now. Losing a seasonal wage or farmland today means hunger and debt — while environmental benefits (cleaner air, restored forests) may appear only later. This trade-off makes poor people resist policies that remove their immediate livelihoods.

Top-down conservation and evictions: Some conservation projects have restricted access to forests or created protected areas without properly compensating or providing alternatives for local residents. Success in biodiversity protection (for instance, Project Tiger) has also created human–wildlife conflicts when wildlife expands into lands used by people, causing crop loss and even deaths.

Energy transition and job losses: Moving away from coal to renewables is necessary for climate goals. But many districts depend heavily on coal mining for jobs. Unplanned mine closures have already led to sudden job losses in some areas, showing that transitions without a clear plan hurt local poor communities. International studies warn that coal districts may not automatically gain enough clean-energy jobs to absorb all laid-off workers without reskilling and planning.

Environmental Protection Measures

India has implemented several policies to protect the environment, such as the Forest (Conservation) Amendment Bill 2023, which acknowledges the role of forest carbon sinks in achieving the net-zero target by 2070. Additionally, the National Clean Air Program aims to reduce air pollution levels by 40% in 100 cities by 2026. While these initiatives are essential for long-term environmental health, they can sometimes impose immediate hardships on communities dependent on natural resources.

Economic Disruptions in Other Sectors

Textile closures due to pollution norms affected 12 million workers. Brick kiln shutdowns impacted migrant laborers in Delhi-NCR. Construction bans and MSME restrictions affected daily wage earners.

|

EXAMPLES Vedanta–Niyamgiri (Odisha): The proposed bauxite mine threatened tribal lands and sacred hills. Local people opposed the project, and the case highlighted how resource extraction can conflict with tribal livelihoods and rights. The legal outcome strengthened tribal consent rights but also showed the deep tensions between mining and local survival. Coal mining & displacement (Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh): There has been repeated displacement of tribal communities for coal and associated infrastructure. Unplanned mine closures have left thousands unemployed, increasing poverty and hardship in mining towns. Protected areas and human–wildlife conflict: India’s tiger conservation has increased tiger numbers (over 3,000 tigers reported), but this success has led to more encounters with people — crop damage, livestock loss, and even human fatalities — affecting poor forest-edge communities. Managing these trade-offs is a pressing policy challenge. |

Environmental Protection Measures Supporting Livelihoods

Green Employment Generation:

Sustainable Livelihood Models:

How to reconcile sustainable growth with the poor’s needs

Just transitions: When moving away from polluting industries (coal, heavy mining), design packages that include early notice, income support, job guarantees, retraining, and local investment so workers and communities are not left behind. International reviews stress that renewable energy can create jobs — but skills and local investments must match the needs of coal districts.

Community rights and benefit-sharing: Implement and strengthen laws that give local communities rights over forests and minerals (e.g., consent, fair compensation, revenue-sharing). Where mining or projects proceed, benefits must flow directly to the affected households. The Niyamgiri example shows the power of local consent.

Livelihood alternatives and local green jobs: Create green livelihoods in eco-tourism, agroforestry, sustainable fisheries, restoration projects, and renewable energy construction/maintenance targeted at local populations. International and national assessments show renewables and restoration can create many new jobs if planned well.

Social safety nets and transitional cash support: While new jobs are created, strengthen safety nets (MGNREGA, targeted cash transfers, food security) to protect incomes during the transition and reduce pressure to accept environmentally harmful work.

Participatory conservation & conflict mitigation: In areas with growing wildlife, use community-based management, fair compensation for losses, better early-warning systems, and land-use planning that reduces risky settlement. This reduces human–wildlife conflict and shares conservation gains.

Learning from Best Practices:

In India, the path to sustainable growth cannot be a single-track push for environmental protection that ignores the poor. Conflict emerges where protection removes livelihoods without offering timely and fair alternatives. The solution is integrated and just: combine environmental goals with strong social measures — legally guaranteed community rights, planned economic transitions, robust safety nets, and targeted green job creation. When policies are designed with local communities as partners, environmental protection and poverty reduction become complementary rather than conflicting aims. In short: sustainability must be social as well as ecological — otherwise it will fail both the poor and the planet.

|

APPROACH: Introduction → Introduce tribal development in India, highlighting the dual challenge of displacement caused by large projects and rehabilitation efforts, while questioning if these two alone capture the real picture. Body → Explain displacement as a central axis (loss of land, livelihood, culture due to dams, mining, industries), and rehabilitation as a counter-axis (compensation, resettlement, livelihood schemes) with examples; then critically show that real tribal development must go beyond these axes to include education, healthcare, livelihood opportunities, and rights-based empowerment. Conclusion → Conclude that while displacement and rehabilitation dominate the tribal development discourse, true progress requires a holistic, rights-based and participatory model that integrates social, economic, and cultural dimensions of tribal life. |

Tribal development in India is a long-standing policy focus, given that 8.6% of India’s population (~104 million people as per Census 2011) are classified as Scheduled Tribes (STs). Tribal communities are concentrated in forested, mineral-rich, and hilly regions, often distant from mainstream development.

Over the decades, tribal development has been influenced heavily by two key axes: displacement due to development projects and rehabilitation through targeted schemes.

While displacement has historically posed a major challenge to tribal welfare, rehabilitation and livelihood support have attempted to mitigate the adverse impacts. Whether tribal development centres primarily on these two axes is a subject of debate.

Displacement as a central axis

Rehabilitation as a counter-axis

Beyond Displacement and Rehabilitation

Limitations of a development framework centred solely on displacement and rehabilitation

While displacement and rehabilitation are undeniably central to tribal development in India, they cannot define it entirely. True tribal development requires a broader, proactive framework: protection of land and forest rights, sustainable livelihood generation, education, health, and participatory governance.

© 2026 iasgyan. All right reserved